With all the buzz surrounding the use of archives in one’s art practice, what intrigues me the most are the machinations allowing such artmaking to happen. This curiosity stems from my experience both as a researcher and a steward of an art archive1. I would say that archives are usually not that easy to access and that typical reproduction guidelines have yet to adapt to purposes beyond the use of archival materials for a research output (typically a paper, publication, or presentation).

For researchers, the guidelines are straightforward. Pay a certain amount for a page or an image that can only be used for your indicated purpose. Make sure to include the institution in your citation or acknowledgments. Once done, share a copy of the research output with the institution.

It isn’t that straightforward when the output is an artwork.

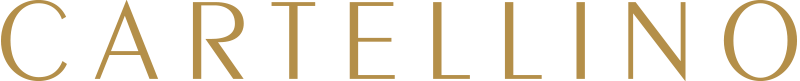

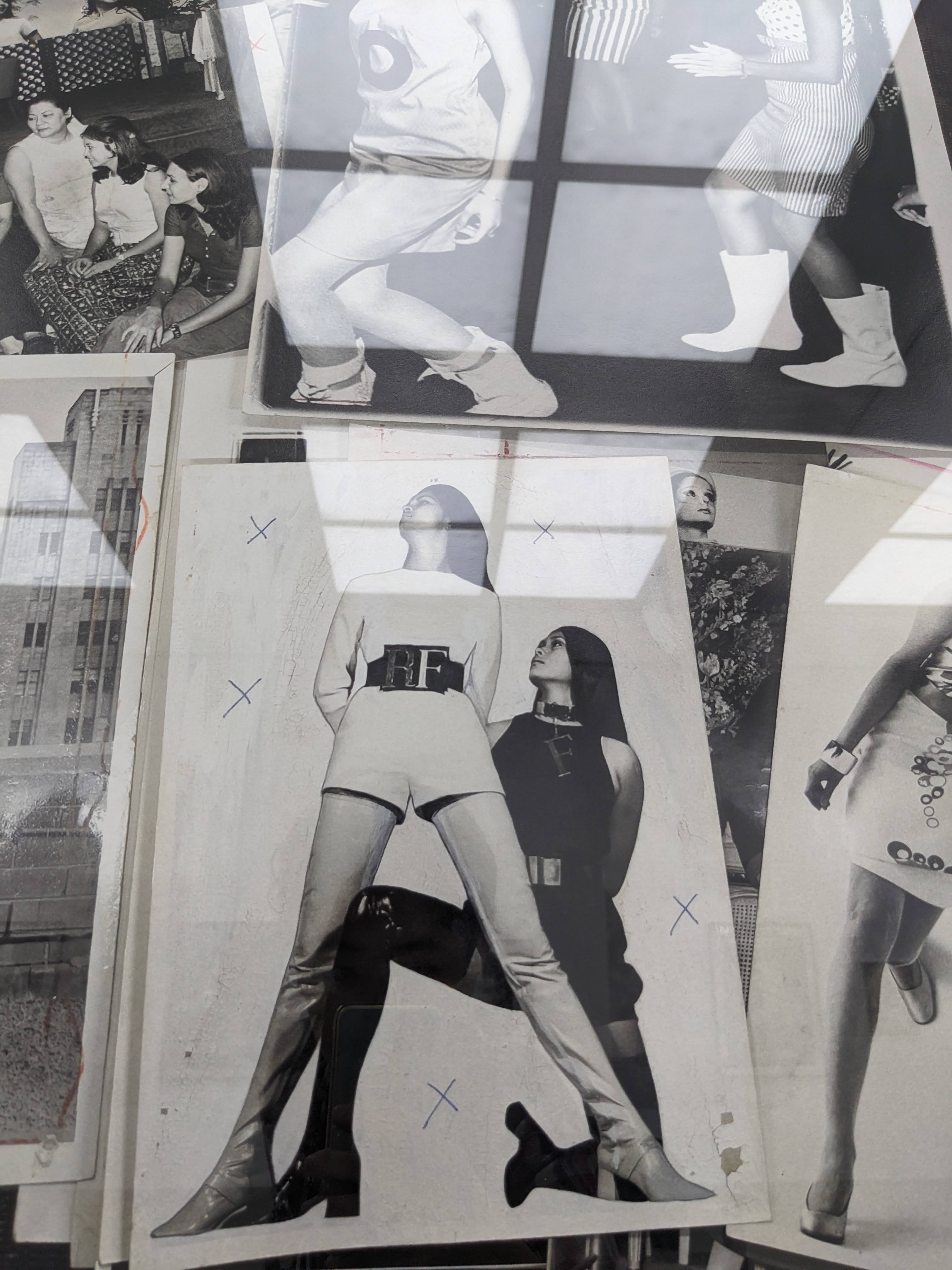

So when I visited Stephanie Syjuco’s Inherent Vice exhibition at Silverlens last September, it was more of the process rather than the subjects and themes that left me wondering. Just from the produced artworks—rephotographed photographs—one would gather that the artist had seemingly unfiltered access to the source archive, as the use case for artmaking is out-of-the-box from usual reproduction policies.

In a video produced by Silverlens, the Filipinx American artist gave an insight into how Inherent Vice started and how she interacted with the photo archive of The Manila Chronicle at the Lopez Museum and Library (LML) for the project:

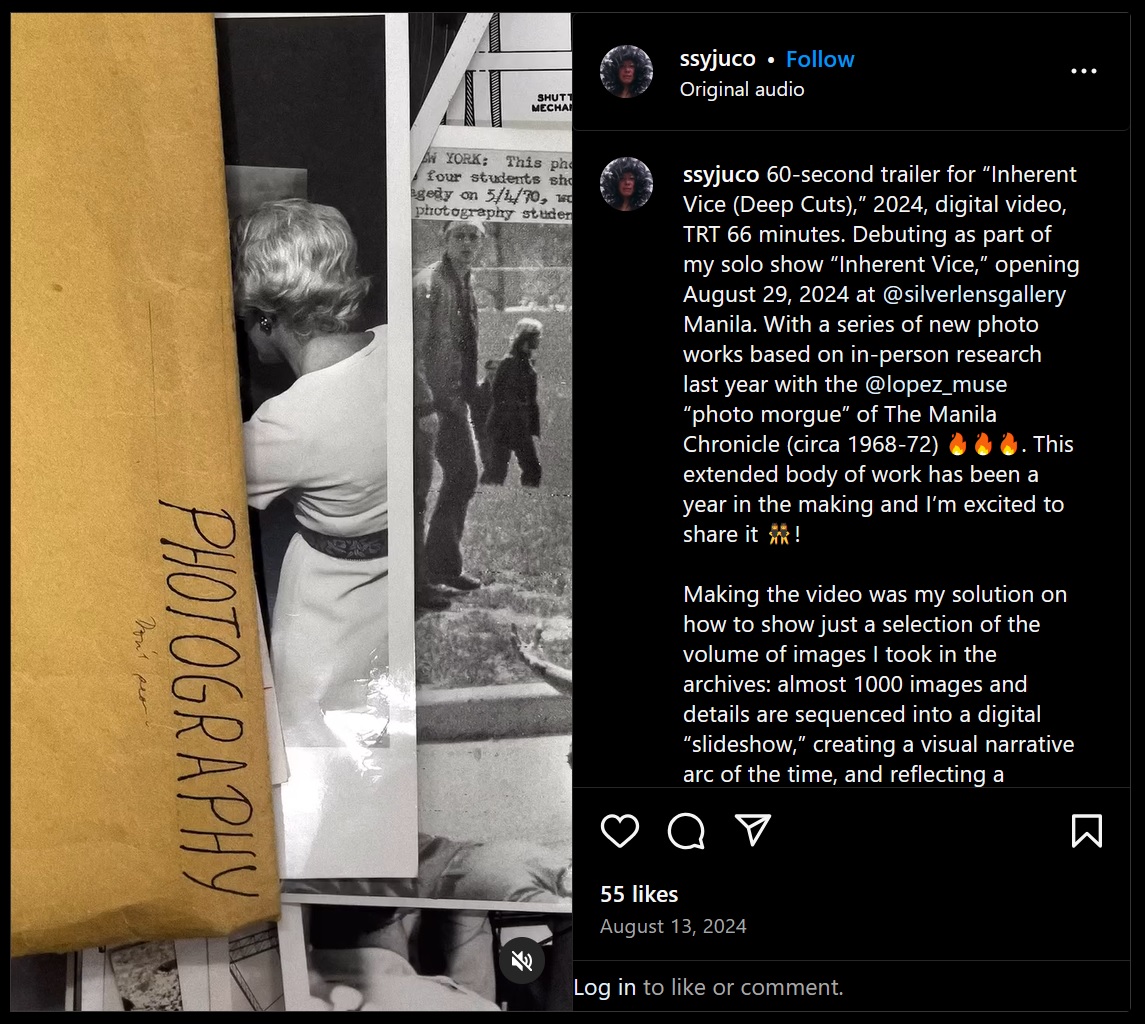

“Silverlens invited me to produce an exhibition here. They had made contact with Yael Buencamino Borromeo [Head of Programs and Audience Engagement of LML] regarding utilizing the photo archives of The Manila Chronicle that fit beautifully into my direction and also interest in working with Filipino-specific archives. Based on that connection, I spent about two weeks working in the Lopez Museum archive literally sitting with the entire photo collection, sifting through it, trying to find images that resonated. In a way, it operated for me as a way to learn about recent Filipino history.”

I also got to visit LML twice (in September 2023, then June 2024) to gather materials for my ongoing research in which I am attempting to look for a Filipina photographer active in the post-war era (the period coinciding with the years The Manila Chronicle was active). However, my experience was much more different from Syjuco’s. It was different in a way that it was relatively more restricted—I accessed their archives through a computer. Accessing the physical materials required me to provide specific codes from the database for the photographs I wanted to view.

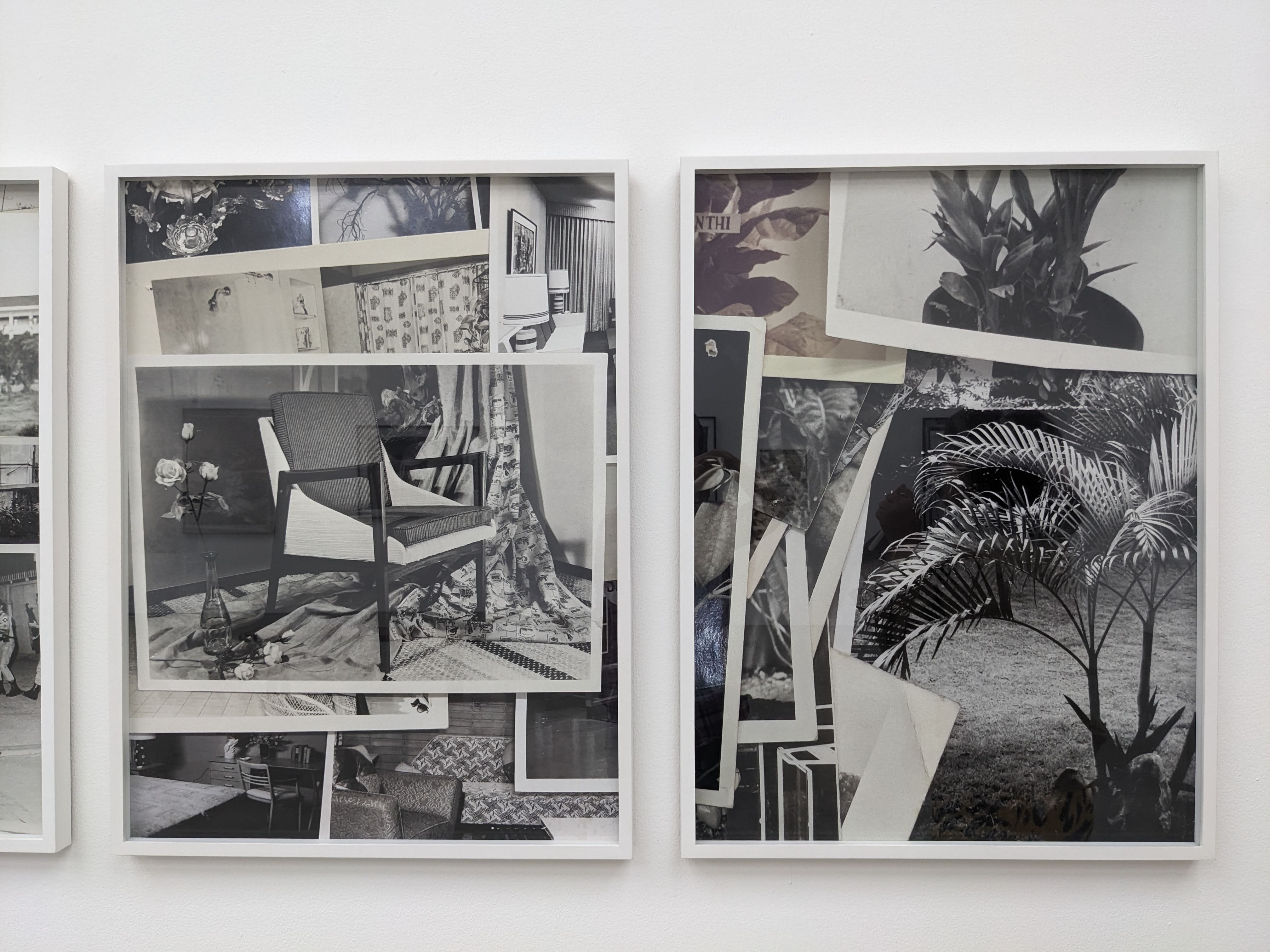

Through Syjuco’s Instagram post, I found that there is a folder named “Photography” in their archive, containing photographs under the topic “Photography.” This thematic folder structure is somewhat similar to the Manila Times photo morgue at the Pardo de Tavera Library and Special Collections (PDTLSC) at the Ateneo de Manila University’s Rizal Library, which I also visited for my research. However, while PDTLSC has a finding aid listing all the available topics, in LML, the digital archive I had access to did not seem to reflect or include the same structure as their physical photo archive. Case in point is the non-existent “Photography” folder in their digital database.

In the aforementioned Silverlens video, Syjuco also shared that many photographs have yet to be digitized, confirming the discrepancy in the materials the clients of LML can access. To me, this raises questions: who can only be granted access to physical archives, and on what basis? In my experience at PDTLSC, you may view the physical photographs by simply requesting specific folders from their finding aid. The staff will deliver these folders to the reading room, and you will be provided gloves to handle the photographs safely. Of course, the staff is also there to ensure proper handling.

In an Art+ article by Marz Aglipay published last October 2024, she quoted Isa Nazareno, historian and consultant at LML, saying, “We have been working on programs to make the materials accessible to the public.” I wonder if there was a parallel effort alongside Syjuco’s artistic intervention in improving access in general, not only for this specific project.

More than the access, there’s also the reproduction component. As mentioned earlier, researchers pay reproduction fees per photograph or page. However, the payment may not be as clear-cut for artists whose works incorporate archival materials and can potentially be sold handsomely in multiple editions.

Entangling the art market into the equation complicates the matter more. I wonder, does (or should) an archive receive a percentage from the sale of an artwork? If an artist intended to use the archives as material for their work, what does a contract or agreement between an artist and an institution look like? Given the rarity of artistic interventions in the archives, at least in the Philippines, such concerns remain open for further examination.

Let’s take a step back.

Two editors ago, the initial pitch to this article tackled a different angle. At that time, it was simply a review of an exhibition that similarly harnessed the archives for their artworks. The artist had a talk, intending to share more about their approach.

It might seem insignificant, but something stood out to me during their presentation: the artist used “library” and “archive” interchangeably, as though they were the same thing. This observation lingered but felt minor compared to what followed.

The trajectory of this piece shifted unexpectedly during a visit to one of the archives that the artist attributed in the show. The archivist expressed surprise when I mentioned the exhibition (in an attempt to learn how they worked together), saying they weren’t aware that their photographs would be part of, or would be an artwork, in a selling show. This encounter made me reflect on the responsibilities of artists when engaging with archives.

And so, I set aside the exhibition review and instead engaged in conversations with archivists to explore their thoughts on artists in archives and responsible collaboration.

First, I asked them to clarify what an archive is—a fundamental knowledge for artists wanting to engage with archival materials in their practice.

For Lucia Halder, Head of Photographic Collection at Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum (RJM), “Archives aren’t just repositories of objects and documents. They depict the ideology of those who created them. An archive tells us more about who created it than what is inside.”

For Mariel Uy, librarian and archivist at the Manila Observatory (MO), the difference between a library and an archive is a matter of time and content: “For libraries, the materials are more current. We try to have an updated collection when it comes to libraries, with new materials on science, journals, and items like CDs or DVDs. When it comes to archives, you deal with older records, old publications. For example, here at the MO, we keep materials dating back to the 1880s.”

I also asked for their insights on how artists can engage with archives responsibly. Dr. Kristine Michelle L. Santos, executive director of the Ateneo Library of Women’s Writings (ALiWW), touched on the complexities of the art market as part of her response: “It’s hard to position myself in the art market. As an archivist, I’m fine with artists using materials for inspiration or knowledge, but the art market complicates things. The reality is that when an artist’s work is bought or sold, multiple parties benefit—not just the artist, but the collectors, dealers, and institutions. This makes things complicated. On one hand, it’s powerful because it gives visibility to narratives that have long been overlooked.”

She also stressed the importance of attribution: “We need to teach the discipline of attribution to artists, even if it’s just in their sketchbooks, to acknowledge the resources they’re drawing from.”

Lucia Halder spoke about the key to continuous, open dialogue between institutions and artists. “The deeper impact comes within longer and sustainable co-creation.”2

In the Philippine art scene, I find artists intervening with archives3 still an unruly4 territory—the exploration is young but the potential outputs are exciting. I continue to observe with keenness.

Images, unless stated otherwise, were taken by the author

Author's Notes

[1] I work as a Coordinator at Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc. (KLFI), where I assist researchers in accessing the archives of art patron Purita Kalaw-Ledesma, among other things.

[2] In 2022, Lucia Halder worked with Kiri Dalena for her Leaky Archives digital fellowship at RJM which evolved into a collaborative research art project titled Snare for Birds in 2023 with Lizza May David and Jaclyn Reyes.

[3] To clarify, I mean artists digging institutional archives as material in their artistic output. I acknowledge that (1) there are artists working as archivists (e.g., Ringo Bunoan as a former Researcher at Asia Art Archive who worked on the archives of Roberto Chabet and artist-run spaces in Manila), (2) there are artists who have been utilizing their personal archives in their work such as MM Yu, or that (3) there are initiatives by artists to build their community archive (be it by location or practice), but those are already different matters.

[4] The term (also used in the article title) is a reference to The Unruly Archive, Stephanie Syjuco’s monograph published by Radius Books in 2024, which reflects the depth and extent of her art engagement with different archives. Aside from being an artist, Syjuco is also an educator. One of the courses that she teaches is named “Art + Archive,” likely an allusion to Sara Callahan’s 2022 book, Art + Archive: Understanding the archival turn in contemporary art. I personally recommend this book to artists who want to learn more about the interlacing disciplines of art and archive.