In the public talk for the Snare for Birds exhibition at the Ateneo Art Gallery last January 5, archivist and human rights advocate Bono Olgado defined colonial archives as a repository built and maintained by an empire, primarily for administrative purposes. Invoking Ann Laura Stoler, he added that these archives conceal, reveal, and reproduce the power of the state. With resources being one of the measurements of colonial power, archiving the colonized reduced them to properties that were cataloged and maintained within seemingly neutral documents and photographs. However, as archives are built by people and institutions who are themselves “infallible” – a term that filmmaker Bea Mariano used during the same talk – this infallibility reverberates even further in those made by the hands of the colonizers.

Cognizant of colonial archives as oppressive sites of memory and history, how did the participating artists in Snare for Birds mediate their experience (which most likely included historical trauma) to the public? Is it possible to reimagine potential histories within these trauma-laden lands?

Immediately greeting the visitors upon entry is a wall for the exhibit text. A usual fixture, one might think, but for a project that rereads a colonial archive (as its subtitle points out), it is a must-read for proper introduction and context anchoring. Especially for ideas such as “colonial” and even “archive” with their complexities and burdens, the main text was enough of a lighthouse on the background and intentions of the collaborative research art project of Kiri Dalena, Lizza May David, and Jaclyn Reyes. To the left of the wall is a traveler’s map in the form of printed annotations on every work (also accessible digitally via a QR code), should one wish to understand their historical context and artist’s intention.

Behind this wall is an audiovisual projection of two collaborative video works referencing the inspiration behind the exhibit title, Snare for Birds. Two eight-minute videos titled “Raubvögel” and “Mga Ibong Mandaragit” play back-to-back. Voiceovers and onscreen texts in German, Filipino, and English read parts of the article “Aves de Rapiña,” translated to “Birds of Prey,” which is also the translation of the two works. This editorial, published in 1908 by El Renacimiento, led to a years-long libel suit filed by zoologist and government official Dean C. Worcester (despite not being directly named in the article) against the newspaper staff. One of the trials ended with a verdict to sell El Renacimiento at public auction, which was then bought by the complainant himself — the “hardest blow of all,” as editor and publisher Teodoro M. Kalaw has written in his memoir.

The archival photographs that the artists examined for their works in the exhibit are from the same culprit, his phantom fingerprint leaving traces behind every shutter, every gaze.

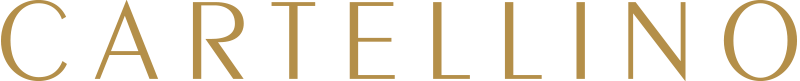

If one has skipped the necessary contextualization through the exhibit notes, Lizza May David’s bold abstract pieces allow for an inviting interpretation and graspable grounding to the surrounding photographic works. To the neighboring images, the quasi-quadrilateral monochrome canvases and the floor piece act as conceptual and emotional bridges, with the latter work even looking like an actual passageway with how it is diagonally positioned at the center of the room.

The emotional aspect is echoed by David in her annotation for the “NegativeSpace” series, with her asking the following: “What colors do archives have? What do you feel in your body after looking at colonial photography? Can you translate these feelings into colors?”

The placement of “NegativeSpace - Silver” beside a photo of a storage space also clues into the inspiration and intention of the works. The framed digital print is labeled as “Photographic Collection of RJM at the Hasenkamp Storage,” with RJM pertaining to Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in Cologne, Germany, the institution holding the colonial archives that the artists worked with.

Aside from colors, the textures are equally evocative. In “NegativeSpace - Red over Red,” the size and imprint of the strokes appear to have been made by fingers. This blood-red surface conjures images of violence that may have happened during and outside the process of making the colonial photographs. “NegativeSpace - Prussian Blue” has a similar texture when seen up close, but when seen from afar, it’s almost black. A portal to the dark past, or an embodiment of unexplored trauma?

The floor piece titled “mmmmmmm,” while appearing black, is also actually painted in Prussian blue. Seeping outside these intensely dark blues are white paint drippings. The textured swirls are similarly in/tense, either evoking or pleading release.

In contrast to David’s works, Jaclyn Reyes’ works are more subtle. She transferred archival portraits on paper by drawing them using different mediums, e.g., white wax and chalk for “Phantasma Series,” charcoal for three untitled works, and chalk and Conté crayons for another untitled piece. In her drawings, the subjects are rendered with softness which is especially evident in the works drawn with white pigment, though the portrayal is also apparent in the charcoal works.

Still on the topic of colors, the papers imitate a sepia patina in old photographs, similar to the stereograph beside Reyes’ charcoal drawing of two old men with an unidentified bird. These men were also in the stereograph sans the bird. This discrepancy cues that Reyes took inspiration from photographs but had artistic liberties in her illustrations.

In resketching these photographs, she also retraces the human captured by the camera. This re/de-capturing of the photographic subject through a different medium recalls Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s idea of the rejection of the shutter:

“Unlearning imperialism is an attempt to suspend the operation of the shutter and resist its operation in time, space, and the body politic in common cause with those who object to it... One should learn how to withhold alternative interpretations, narratives, or histories to imperial data, how to refrain from relating to them as given objects from the position of a knowing subject. One should reject the rhythm of the shutter that generates endless separations and infinitely missed encounters, seemingly already and completely over.”

Her drawings are a step away from the colonial hand behind the shutter, and a step towards the ones in front of it.

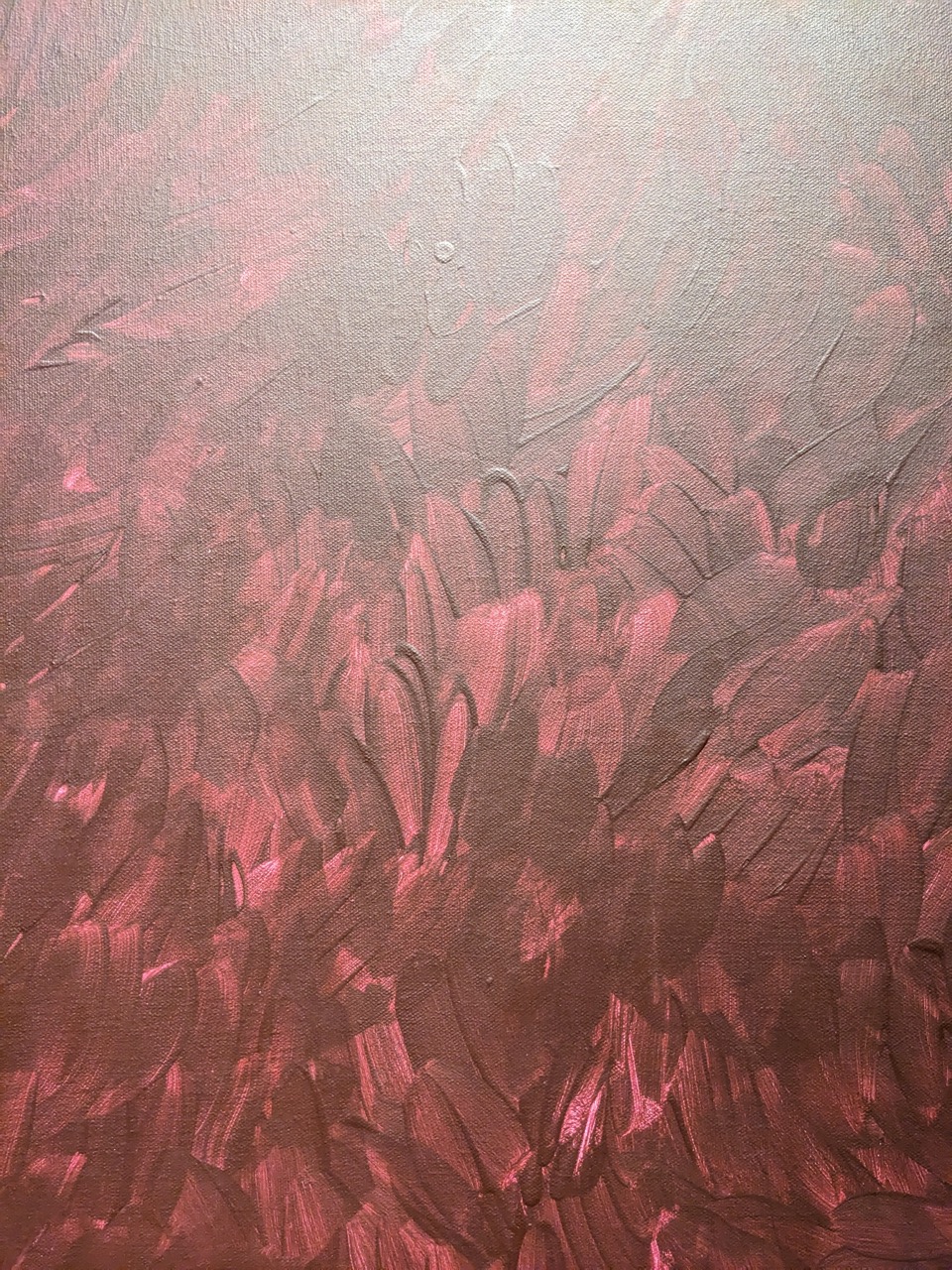

Sharing the space with David’s floor piece is Kiri Dalena’s floor-to-ceiling cloth work titled “Tagalog Woman” with life-sized prints of three overlapping female figures. All but one stare at you, as if asking: why are you looking? There is no escape. Even going behind the cloth, the gaze and questioning continue.

Beside this full-height cloth is another oversized piece aptly named “Lubid (Cordage).” The work in abaca resembles a long braid of hair, its curvatures emanating a feminine quality that oscillates with “Tagalog Woman” and the “Manila Women Series” print on archival paper nearby. More importantly, the actual act of braiding this humongous material suggests power, labor, and resistance. These are also internalized in the aforementioned pieces as well as Dalena’s prints on rice paper, “Philippine Constabulary Sequence (Francisco)” and “Philippine Constabulary Sequence 1, 2, and 3.”

Dalena’s photograph prints can be interpreted as dismantling what Michelle Caswell described as “chronoviolence [which] asserts that the linear white way of constructing time is the only legitimate way.” With Dalena referencing Don Francisco Muro, the man featured in the famous Igorot sequence, she reclaims the colonizer’s fabrication of juxtaposing narratives (e.g., before/after, naked/clothed, savage/civilized) by breaking the temporal and visceral and bringing them into the now, prodding our contemporary views on police forces, womanhood, and servitude. Still, Dalena does not intend to leave the past but trace a connection from our colonial history to the present.

Bookending the exhibit with another video work, Dalena presents a 14-minute video titled “Felizardo, Taken in 1906.” During her online residency with RJM in the midst of the lockdown, she managed to do remote research about Felizardo and consultation with forensic pathologist Dr. Raquel Fortun, both of which she posted on a microsite. The project was supposed to end in 2021 with the microsite and an RJM exhibit, but Dalena shared during the opening talk that they realized this is something that should continue.

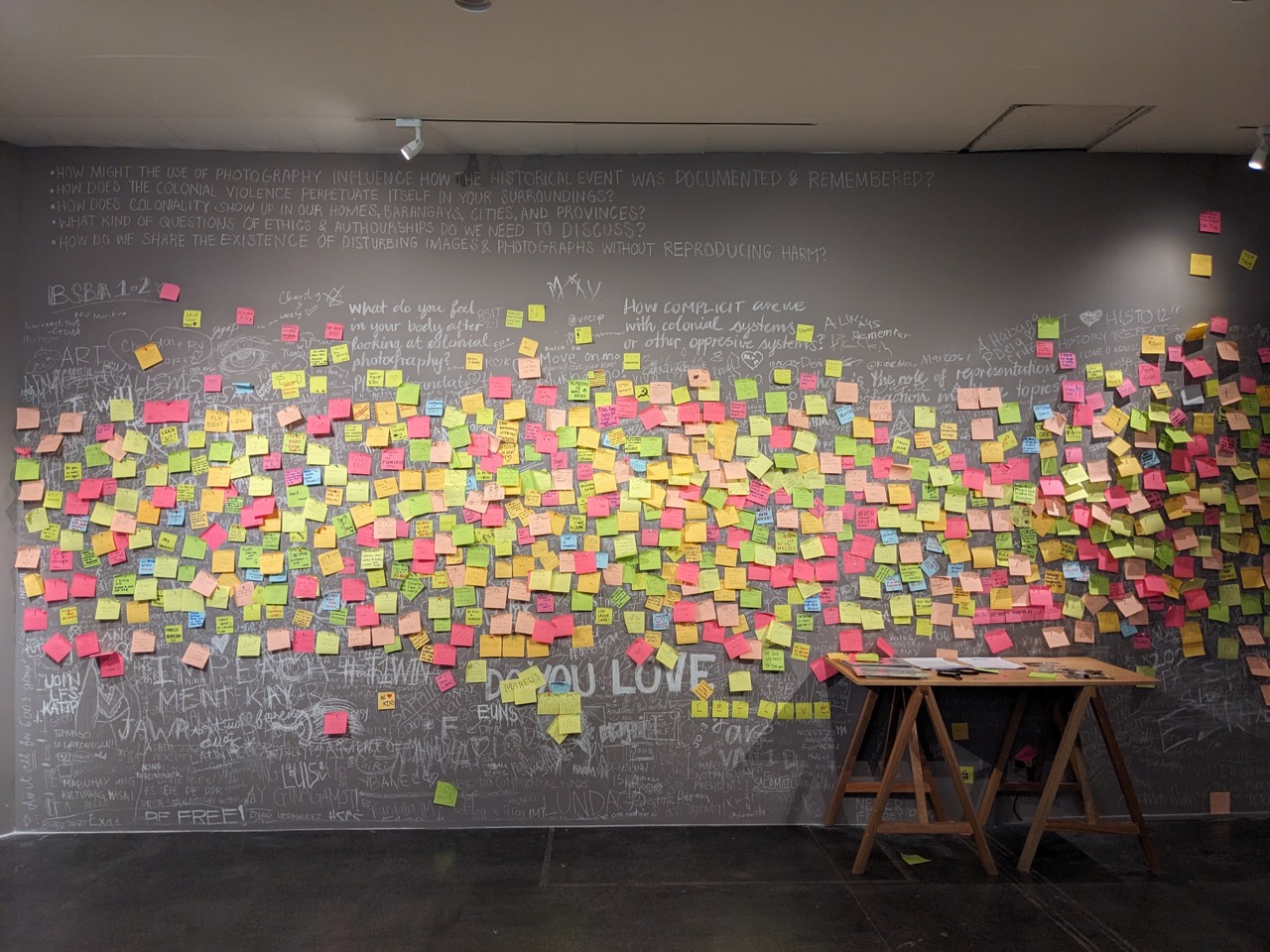

It would be amiss to skip the freedom wall, arguably the most prominent area in the room with its blizzard of neon-colored sticky notes and chalk writings. (As an aside, the table storing the writing materials also has the photo documentation and workshop materials from the Snare for Birds iterations in Ang Panublion Museum in Roxas City, Capiz and Alfredo F. Tadiar Library in San Fernando, La Union. The inclusion of these is informative as you can glean how the iterations slightly differ in language and presentation to tailor the ideas explored by Snare for Birds to different local audiences, geographies, and histories.)

During the exhibit opening, as expected, the wall was orderly. The viewers were prompted with eight questions to respond to. “How might the use of photography influence how the historical events were documented and remembered?” or “How do we share the existence of disturbing photographs without representing harm?” and other prompts were commendably thoughtful.

Three weeks later, I viewed the exhibit again when I toured a friend visiting Manila. By then, the visitors have run with the “freedom” in the freedom wall, the prompts and related answers now overshadowed by more visible chalk writings and sticky notes not connected to the exhibit, such as “Follow me @[handle]” or “[Name] was here.”

My third visit was three months later. Five prompts were now at the top left of the wall with a higher chance of being perceived by the visitor. Still, the responses are a mixed bag, leaning towards randomness.

Despite this, my optimistic take is that these visitors, regardless of the relevance of their reactions, have interfaced with the colonial archives through the artists’ mediations one way or another. To carry these pieces of history, no matter how small, is a start.

Through the artists’ reimaginings — David’s abstractions of emotional and spatial incarnations, Reyes’s re/de-capturing of the subjects, and Dalena’s reconfigurations of the archival photographs — different portals to potential histories have been opened. At the very least, a section of our colonial history was brought to light by the exhibit.

But remembering is not enough. Jewish historian Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi once said: “The antonym to forgetting is not remembering but justice.”

The next question to us then, after rereading a colonial archive, is what does liberation mean in the present?

In the future?

---

Subheading quotes are from the English translation of “Aves de Rapiña” published in Aide-de-Camp to Freedom by Teodoro M. Kalaw, translated from Spanish by Maria Kalaw Katigbak. Published in 1965 by Teodoro M. Kalaw Society, Inc. KLFI Collection.

Other referenced materials:

Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. Verso, 2019.

Caswell, Michelle. Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work. Routledge, 2021.

Harris, Verne. “The Archival Sliver: Power, Memory, and Archives in South Africa.” Archival Science, vol. 2, 2002.

Stoler, Ann Laura. “Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance.” Archival Science, vol. 2, 2002.

---

Lk Rigor is an art writer in the spheres of photography and archives, as well as the multiple strings that bind them to everything else.