Within the formidable parlance of artspeak, few terms come close in ubiquity and vagueness to that sneaky little word “gesture.” The word has been rendered over the years as mutable, clandestine ground, leaky with meaning. “Gesture within its multiple forms,” observed art historian Lia Markey, “is the most primal and yet one of the most complex media for communicating ideas and emotions to others and the self.”

To gesture, on the one hand, is to signify an artistic mark. But, on the other, it is an intuitive language beyond—or before—language, a form of communication that’s sensorial and physical all at once. The gesture can be performed, and in that performance achieve a meaning that fluctuates from the viewer of the gesture to the gesturer himself. In the process of writing, a critic gestures at an artist’s intent, only to find something new about the art in the process. Gesture is a wormhole: you open a door to another door.

The Future Life of Gesture, an exhibition at Arte Bettina in Makati City, delves into the fluidities of the artistic gesture. How do we pay attention to gesture and its various manifestations? And what can we learn from this type of awareness? Writing in the show notes, Carlos Quijon Jr. situates the gesture within an increasingly digitized artistic landscape, asking, “How do we think about the artist’s gesture and how it resists, converses, or converges with, or instrumentalizes these technological developments?” Featuring the works of six artists whose varying practices include repoussé, printmaking, and painting, The Future Life of Gesture open-endedly pursues these questions, offering the concept of gesture as a foundation for examining relations of the artistic self, medium, and material.

One of the major preoccupations of the show is the body. Corroding into gleaming dust, the bodies depicted in Dharmabum’s acrylic paintings seem to be on the verge of vanishing. Hues of pink emerge like flecks of light amid the nightscapes in which the body is immersed. One such scene takes place in the bedroom, leading our eyes to a spectral, etched-out body, its bloody traces left behind on the bed.

In another set of scenes by Emerson Ebreo, a runner kneels as he prepares to go for a run. The effect is the complete opposite of Dharmabum’s works. Here, the man’s body is the only figure in focus while the rest is blurred in sweeping strokes of distortion. Dharmabum and Ebreo’s focus on the body reveals an attempt to showcase the human form as an open container, capable of both disappearing and asserting itself, susceptible to violence but also aware of its innate strength.

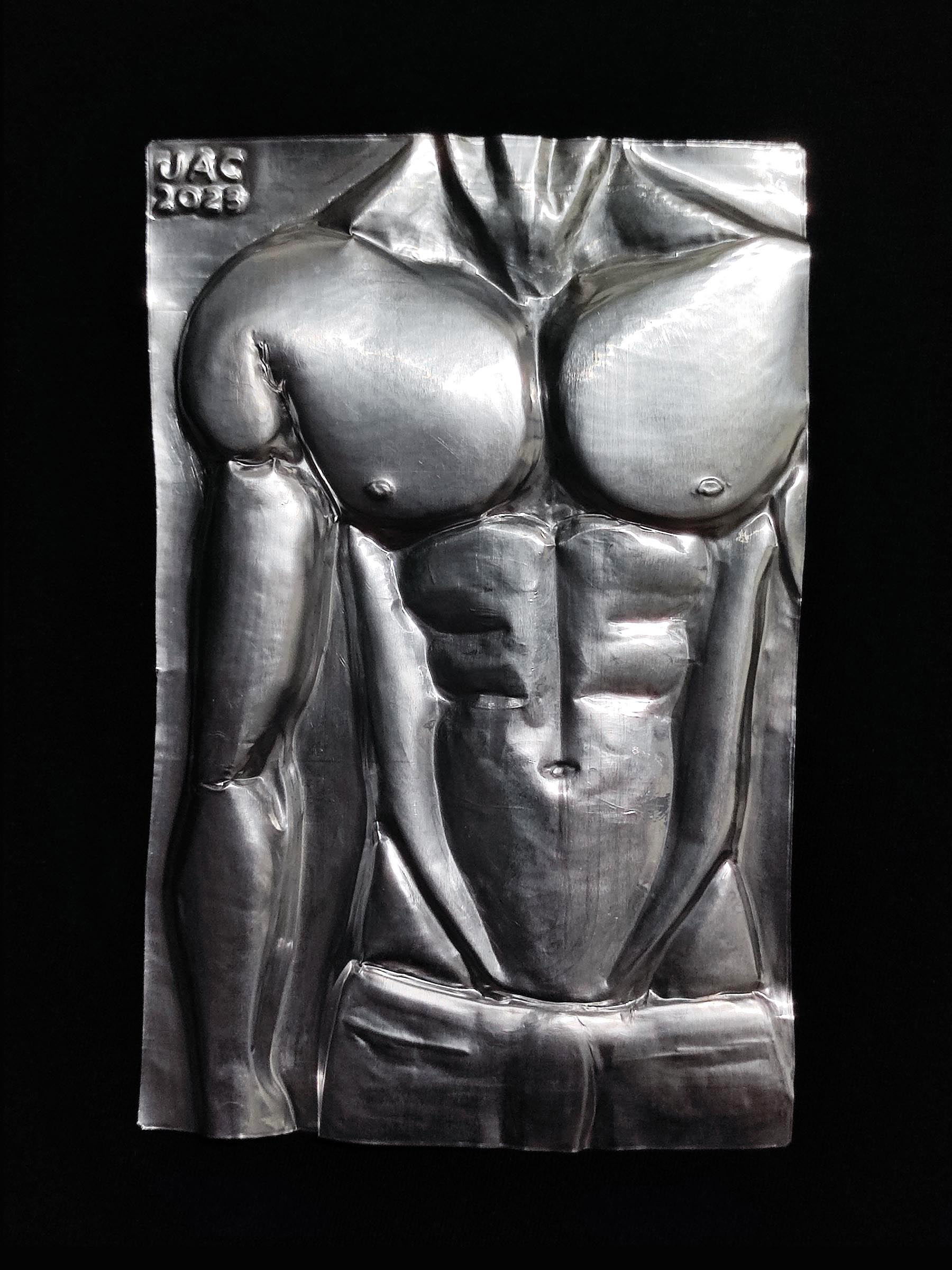

The body’s gestures reveal contradictions which oftentimes elude even us. Examining Dharmabum and Ebreo’s pieces alongside each other, we may identify with bodies holding out for release and rapture. This depiction of bodily contradictions emerges most palpably in a series of repoussé works by Baguio-based artist Jandy Carvajal. Delicately engraving sections of a body’s musculature onto plates of metal, Carvajal’s metalwork process melds fragility with force, and in turn yields an intricately revealing gesture about the body. Here, the masculine physique—its pose and stance chiseled out on carefully crafted aluminum sheets—highlights the performance of gesture on both bodily and artistic scales.

Another thread of questioning the exhibition follows relates to futurity. Quijon asks: “How do we think about artistic gesture as its own techne that anticipates and shapes its own future life?” The ancient Greeks used that word—techne—to describe knowledge derived from an art or craft, something learned from continuous practice as opposed to pure theory. If the gesture arises as a kind of practical craft, then what knowledge does it produce? And what can that knowledge do to shape art’s future trajectories?

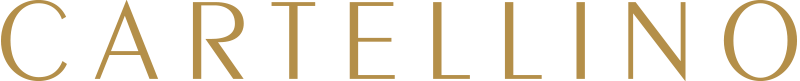

One way the show responds is by posing even more questions. “Where does a body end?” is both the guiding inquiry and title of Luis Antonio Santos’ framed fiberglass resin work depicting a form akin to a rusted roof. The body, in Santos’ imagining, materializes as a fissured shelter, a metaphor for the body’s varied vulnerabilities. Matina Partosa takes on a similar approach with her oil painting, “The softest lips in the universe,” which illustrates a blue sky and a shining sun at its heart. The work’s naturalist glow complements the overt romanticism of the title despite no actual lips being found in the painting. In both works, gesture acts to elude direct meaning and instead bring forward its own off-center kind of logic.

In an essay, Markey references the Italian artist and polymath Leon Battista Alberti in his 1435 work On Painting, connecting his words about painting with the potency of the gesture. "These movements of the soul are made known by movements of the body,” Alberti observed. Perhaps that correspondence—between the soul and the body—defines the unerring vitality of the gesture today. The Future Life of Gesture grapples with these links in subtle yet impactful ways, drawing us closer to the symbiotic movements of the soul and body.

The Future Life of Gesture features the works of Matina Partosa, Emerson Ebreo, Jandy Carvajal, Jem Magbanua, Dharmabum, and Luis Antonio Santos, and continues at Arte Bettina in Makati City until October 1.

Sean Carballo is a writer and undergraduate from the Ateneo de Manila University.

Images courtesy of Arte Bettina.