In Yuval Noah Harari’s 2015 bestselling book Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, the Israeli historian and public intellectual developed the term “dataism” to describe the ingrained philosophy that worships big data. Dataism, Harari noted, has declared itself over the years as a kind of religion which puts supreme value over flows of information and huge systems of data which have the capacity to dictate human behavior. “In its extreme form, proponents of the Dataist worldview perceive the entire universe as a flow of data, see organisms as little more than biochemical algorithms,” Harari said in a 2016 essay.

Hypercomplex, an ongoing show at Artinformal Makati, is Japanese artist and designer Wataru Sakuma’s response to Harari’s critique of dataism, particularly in light of the ongoing discourse of artificial intelligence. The solo exhibition, which situates AI interventions as artistic processes, deploys a swath of data points to imprint abstract forms onto paper, and asks us in the process to ponder on the relationship between artistic activity and technological advancement.

Across Sakuma’s paper works in Hypercomplex, material and concept are juxtaposed, raising questions about agency, will, and labor. The title alludes not only to the machine learning operations involved in AI, but to Sakuma’s process as a whole. As chair of MASAECO, a business specializing in creating “unique handmade paper product[s]” from sustainable sources, Sakuma’s ties to paper run deep. Beyond perceiving it as a medium for art, paper for Sakuma asserts something existential; paper, one of human society’s most reliable technologies, is a way of inscribing life. And in Hypercomplex, the forces by which paper survives are complicated further.

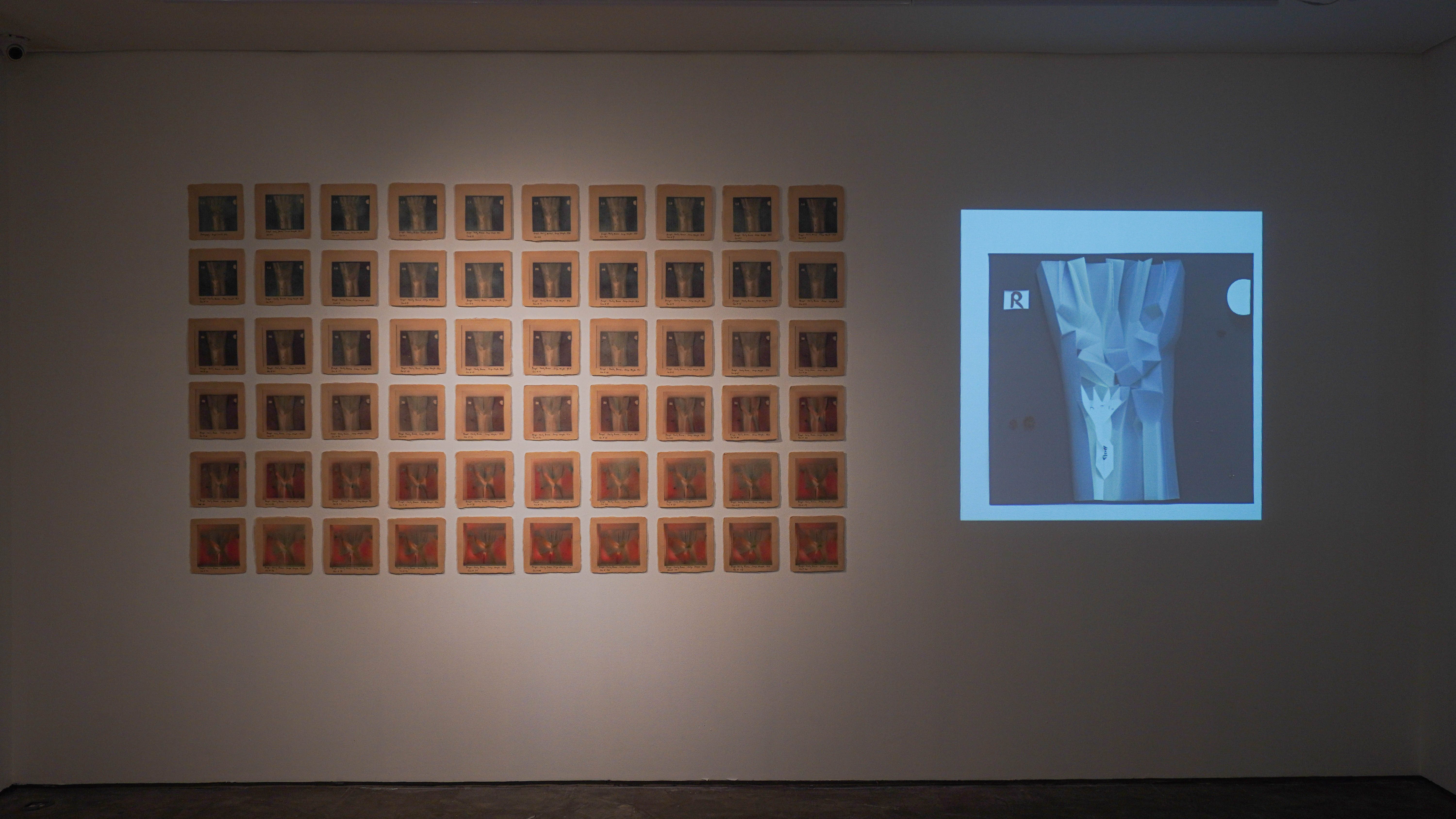

Meshing AI technologies and sublimation printing, the works showcased in Hypercomplex are portals into a transitory world, where the fragility of paper comes into contact with the fast-paced motions of AI. The process creates prints that are repetitive and foggy. Layered and blurred, the prints are labeled by “generation”, indicating each step in the process as a kind of genealogy, though the degree of Sakuma’s manual interventions is unclear throughout.

But to read Hypercomplex as a genealogy also invites suspicion about the source of the original. The show does not give much information about how to read the originary generation of the work but instead, asks us to dwell in its obfuscation. We get glimpses of green and yellow and an X-ray-like abstraction, but we are ultimately given little to hold on to, particularly regarding the processes involved in creating such a work. In turn, the feeling of going through the show is like being thrust into an alien planet with no governing logic.

A similar feeling occurred in Sakuma’s previous shows, which aimed to blur perception and challenge our notion of sense-making in the process. Blurred, from last year, toyed with historical records to undermine the exploitation of historical discourse for political aims. Critiquing the revisionist history at play in Filipino politics, Blurred was refreshing in its textural dissonance, twisting and turning cutouts and pulp paper into strange forms that doubled as social commentary about the manipulation of history. However, in Hypercomplex, Sakuma’s critique scans with less urgency, particularly due to the fact that it remains firm in its abstraction all throughout. As a result, the stakes of the show float in a realm that just barely eludes our comprehension.

“Sakuma subjected his art making to several phases of interventions. . . all coalescing into the final destination that is manual human labor,” reads the show notes. The fragility of paper, and the hazards which undergird it, seems subsumed by the technological sheen of the AI technologies at play here, which imbues the show with a post-apocalyptic nihilism. However, left with little to grasp at, the show’s indications of manual human labor seems to recede into a kind of uneasy anonymity.

One asks: what exactly does this “manual human labor” entail? In the midst of abstraction, where are we as humans situated? And if the final destination of this show remains centered on the human, where does that leave our ecological relationship to paper? Despite an attempt to link paper and AI, the show’s exploration of this relationship underwhelms, primarily because it still feels too tethered to its AI machinery, leaving little of humanity behind.

But perhaps that is the point. This could after all be the natural endpoint, that vacant repetition can only yield falsity, and that life, as we are doomed to repeat it, only fades over time. Hypercomplex, suggests in its succession of AI generations, that as we draw deeper into technological advancement, this loss deepens, darkens, just as its own repetitions rust and redden. It is a fitting conclusion for a show dwelling, and perhaps even relishing, in the ambivalence and uncertainty of our future selves.

Hypercomplex continues at Artinformal Makati until August 25.

Sean Carballo is an art writer. He recently graduated with a degree in English Literature from Ateneo de Manila University. His writing has been published in ArtAsiaPacific, Art+ Magazine, Plural Art Mag, and Cha: An Asian Literary Journal.

Images courtesy of Artinformal.