More than being a photography enthusiast and an art writer, being a Filipino was my primary lens as I looked through the Living Pictures exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore (NGS). For a show touted as “the world’s first-ever survey of photography's histories across Southeast Asia,” a visitor from a country within the said region would be naturally curious to see how their nation was represented.

Flipping the pages of 32 Volumes

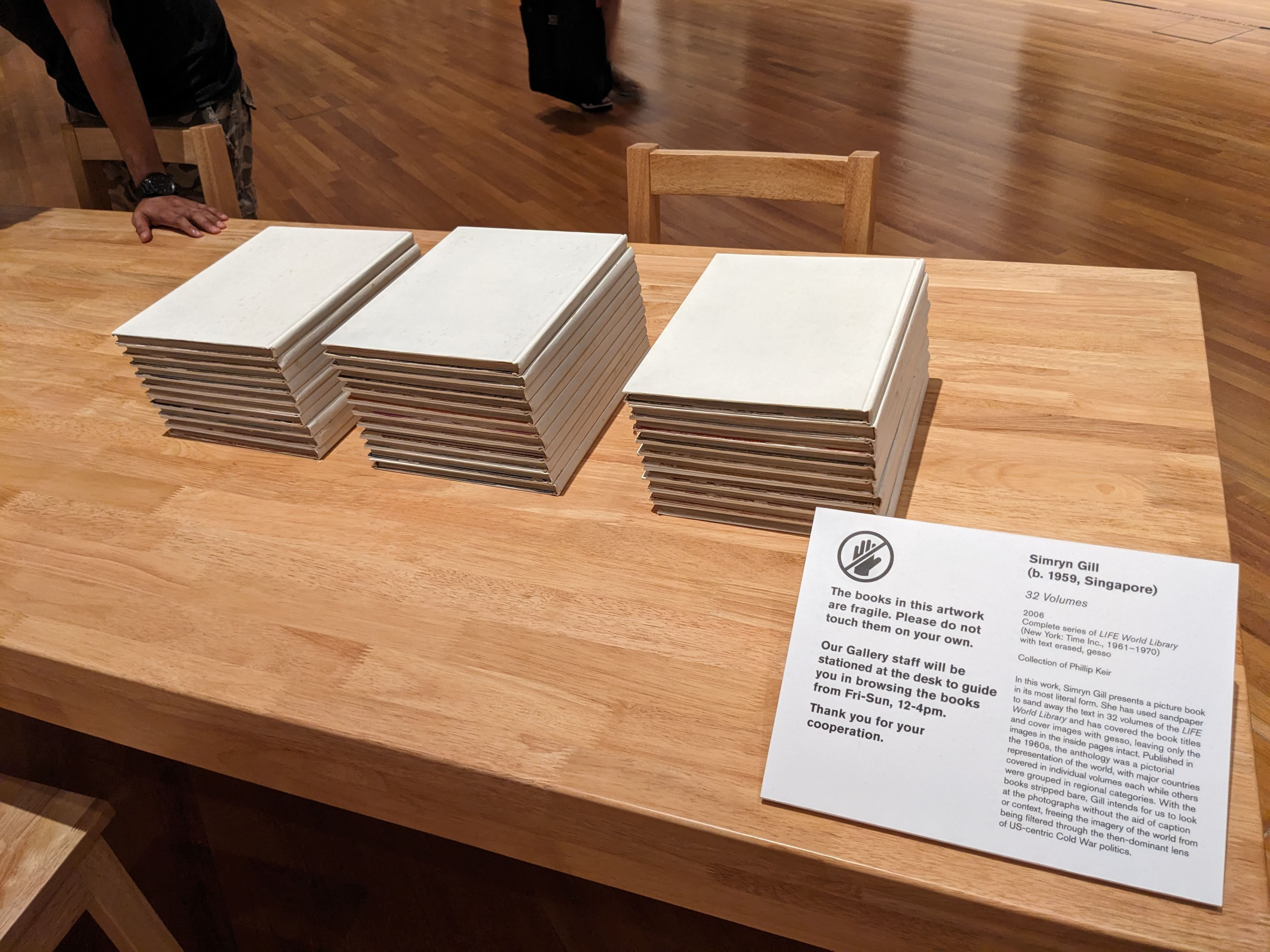

Near the entrance of the last gallery, an inconspicuous table of plain white books is positioned. Stopping to peer inside the books, one would discover that the pages are also devoid of text. Only photographs remain.

In her work ‘32 Volumes’, Singapore-born artist Simryn Gill altered the volumes of LIFE World Library by masking the covers with a white paint mixture and sandpapering the printed text. The result turned each volume that was once about a specific country or region into a photo book without context. In its original state, it is straightforward how countries like the United States and Spain had their own dedicated volumes, while some like the Philippines were featured within a volume for their region such as Southeast Asia.

I was intrigued if I could locate photos shot in the Philippines so I approached the gallery staff to browse the books. She gladly obliged and even quizzed me if I knew how long we were under Spanish control after learning that I was from Manila. Interestingly, my correct answer surprised her because she said that other Filipino visitors she asked (younger ones, she observed) didn’t know.

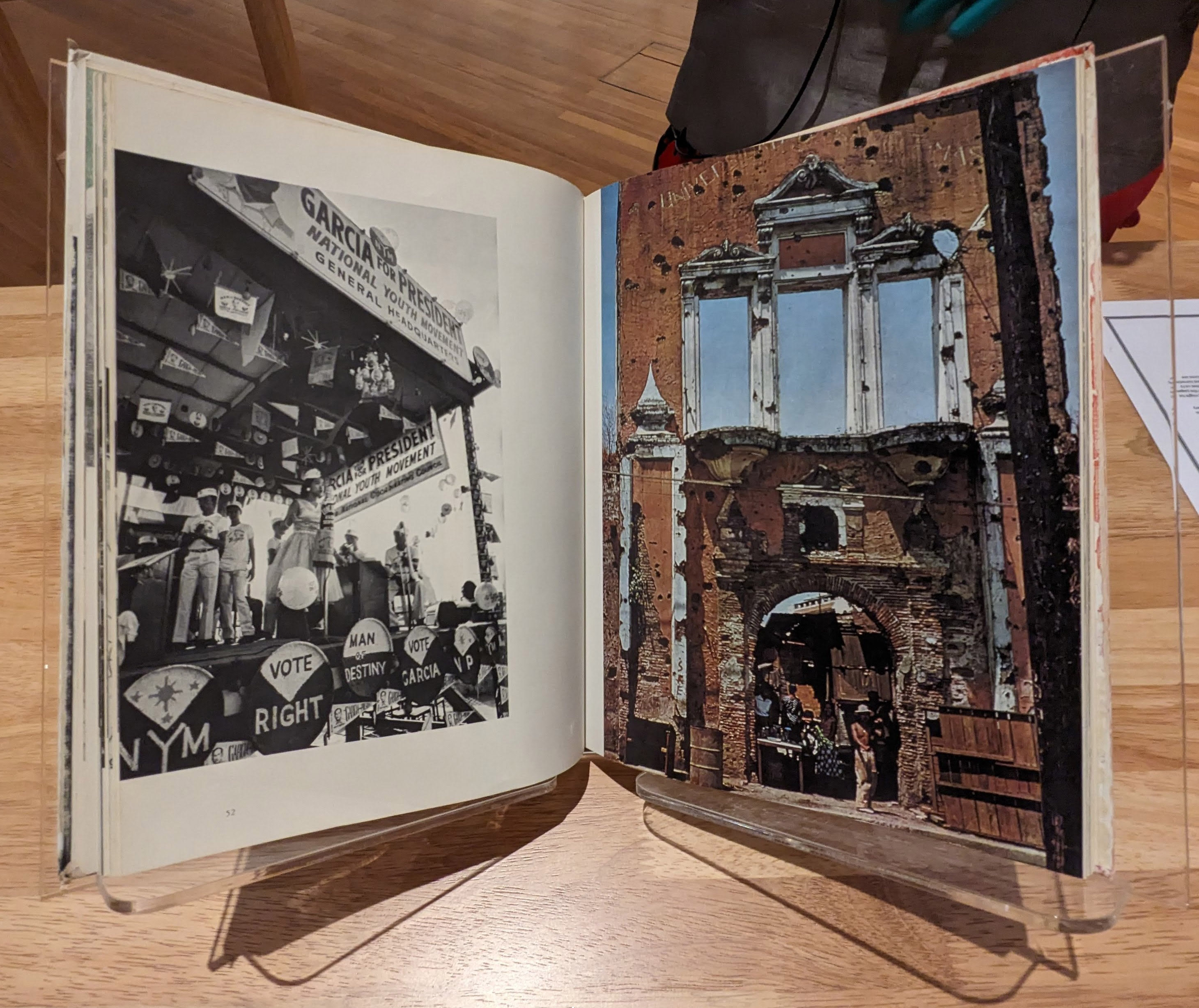

As she gently flipped through the delicate pages, I finally spotted it. At the bottom of a full-page photo, there were bilaos (circular baskets) painted with the Philippine flag. On the opposite page was a photo of ruins with “Universidad Santo Tomas” engraved at the top. Even without captions to confirm it, I pieced out that they were taken in the Philippines.

Aside from deconstructing the relationship between text and images, ‘32 Volumes’ is also an inquiry into how the Philippines and other constituent countries in Southeast Asia were viewed by the West considering that LIFE was an American publication. This interrogation is just one of the overarching themes explored across the five sections of Living Pictures, most evidently in the first part.

Walking through the five sections

Gill’s work is in the fifth and last section of the exhibit called Contemporary Imaginations which is also the area where most of the works from Filipino photo-based artists are displayed. Near ‘32 Volumes’ is Kiri Dalena’s ‘Erased Slogans’ and further down the gallery are works from Poklong Anading, Wawi Navarroza, and Stephanie Syjuco.

Exhibition view of works by Filipino artists in the Contemporary Imagination section. Left: Kiri Dalena’s ‘Erased Slogans’ (2008-2016). Right (clockwise): Poklong Anading’s ‘anonymity’ (2009), Wawi Navarroza’s ‘Start Here, a Lesson on Looking (Self-Portrait with Mandarins)’ (2019) and ‘May In Manila/Hot Summer After (After Balthus, Self-Portrait)’ (2019), and Stephanie Syjuco’s ‘Block Out the Sun’ (2019).

My tour with one of the curators, Goh Sze Ying, started with the first section Colonial Archives which presents Southeast Asia through the lens of European colonists. Thinking afterward about the absence of Philippine photographs in this section, I realized that Syjuco’s work in Contemporary Imaginations – the last section dedicated to how artists are wielding images now to evaluate the past, present, and future – is a fitting surrogate that does not only show a part of our troubled history but also and more importantly, challenges it.

In ‘Block Out the Sun’, Syjuco photographed the images of Filipinos in the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, an expo that included a “human zoo” where they flew indigenous people from the Philippines, Central Africa, and Japan to the United States to exhibit their culture and their “normal” day-to-day lives. What’s different in the resulting photographs is the inclusion of her hands that blocked out their faces.

In her interview with one of the curators, Kenneth Tay, Syjuco shared:

“I find irony in the motto ”let there be light”—as if shining light on something will lead to truth or enlightenment, when in the medium of photography, images were used to conscript and assign value when used as ethnographic tools. Block Out The Sun … also considers what it means to deflect the image itself, and prevent it from functioning in its original intent.”

Moving onto Portraits and Performance, the second section shifts to the perspective of the colonized as they became aware of the power of image-making. Here, Masferré has portraits from the Mountain Province that are in dialogue with German photographer Hedda Morrison’s photographs from Sarawak, Malaysia. Sze shared with me that there were only two photos from Masferré because the others were also on display for another ongoing NGS exhibition called Familiar Others which explores how the “Other” looked at themselves and presented it through art.

The Philippines is missing in the third section titled In Real Life which probes into the construction of reality through pictorial and documentary photographs. Perhaps, the exhibition could have potentially included any of the 5 Photographers acknowledged as the masters of Philippine photojournalism. Notably, Romy V. Vitug was particularly passionate about elevating photography as an art form whose works could be placed beside other pictorial photographers. The documentary photographs that they chose in this section touched on key events around Southeast Asia at that time including the aftermath surrounding the proclamation of Indonesian Independence in 1949 and the contrasting depictions of the Second Indochina War (Vietnam War) between photojournalists covering for American news versus snapshots by Vietnamese photographers. As a Filipino viewer, these events around Southeast Asia provided me with an opportunity to reflect on the interconnectedness of the region's history and the role of photography in documenting and shaping it.

For New Subjectivity, the fourth section that illustrates the experiments with photography as a medium, Johnny Manahan and Nap Jamir II are included. In Jamir II’s ‘Auto Retrato Series #2’, “blood” oozed out of the final frames after his character stabbed his chest.

The exhibition does not only end within the museum walls. Also touching on the ubiquity of photographs on the internet, Living Pictures also had an Instagram showcase that featured four photographers, including Filipino photographer Veejay Villafranca.

Finding the Filipino

Taking everything in, I found a deeper appreciation for the Filipino through the lens of the shifting consciousness around Southeast Asia, through living photographs. Living Pictures is a substantial attempt not just to establish the region’s historical beats of and through photography, but more critically, to invite interest and inquiry into the region’s idiosyncratic practices using photography, their connections and intersections.

Living Pictures: Photography in Southeast Asia is currently on view at the National Gallery Singapore until August 20, 2023. More details about the tickets here.

Lk Rigor is currently pursuing MA Art Studies in UP Diliman. Aside from being a curator, she dreams of becoming a cat lady someday.

Exhibition view images courtesy of the writer. Images from Veejay Villafranca used with permission.