It’s often been said that the space holding art has as much impact as the art itself.

The choice of lighting and background, the spacing of pieces, and how walls and barriers set foot traffic can shape a narrative and amplify themes, messages, and emotions that the works are attempting to communicate.

This is especially true in the second run of Weaving Women’s Words on Wounds of War (WWWWW), a collaborative, multi-creator exhibit curated by Marian Pastor Roces and developed by Karl Castro at the Ateneo Art Gallery (AAG), in partnership with the Ateneo de Manila University Department of Political Science and the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation.

Its first version took place between April and May this year, in a different wing in the AAG and with a more open-ended layout and brighter lighting.

The exhibit, more than a history project, more than a testimony, more than a political statement, is first and foremost an art project, and with that comes the medium’s possibilities and limitations.

While the focus is on aesthetics, it’s undeniable that this is a project heavy on context and intertwined with ongoing political realities faced by indigenous and minority ethnicities in the Philippines.

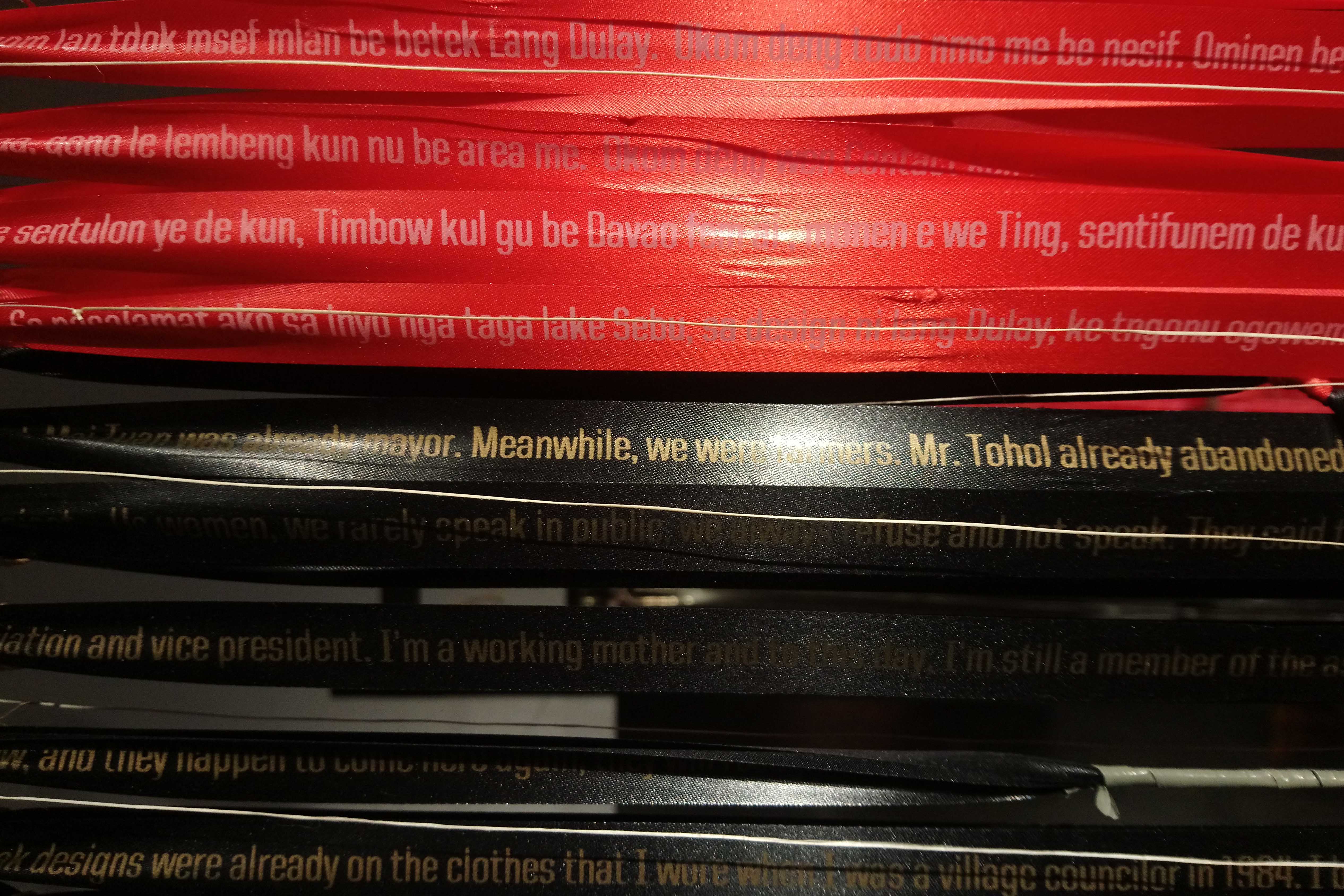

WWWWW features six works, named around six attributes of spirit, their short titles being: Endurance, Amplification, Discretion, Tenacity, Grace, and Equanimity. Each work contains autobiographical recollections from women from six different locales in the Philippines: Sultan Kudarat, Cotabato, Lake Sebu, the Cordillera Mountain Range, Jolo, and the Sulu Archipelago.

While some might describe these short titles as too lofty, the words are borne of blood and describe the experiences of women from the margins of Philippine society who suffered under Martial Law. Many of them witnessed the horrors of incursion, resistance, war, and displacement, amplified by gender-based violence.

A burned mosque where a massacre occurred is recreated on acrylic based on the memories of locals, hanging in the center of the room and lit like an altar, all while another such model is wrapped in the style of a traditional Islamic burial.

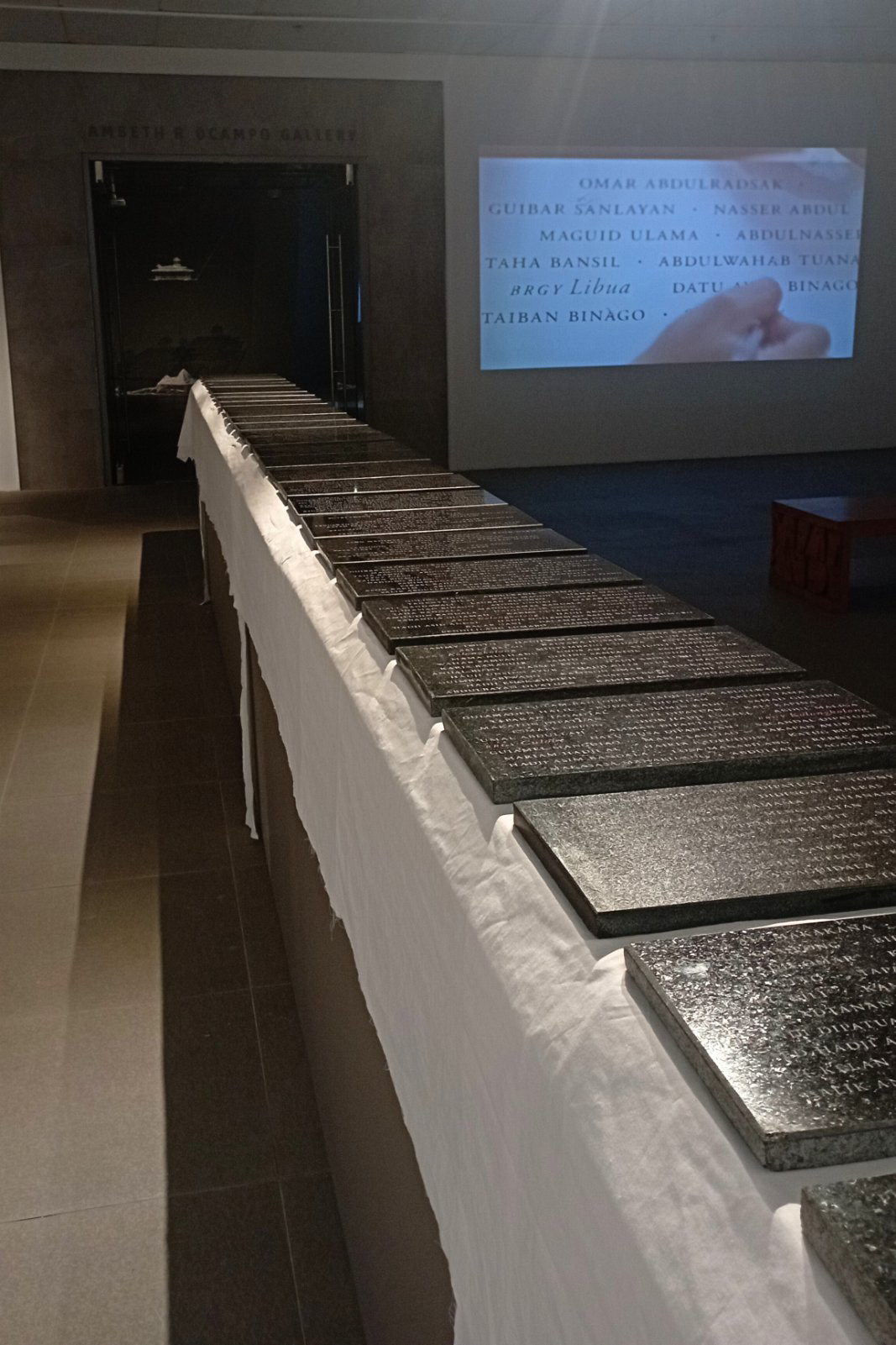

Granite slabs hold the names of Muslims and the villages they hailed from, who all met their end in a mass grave in periodic killings that took place over a month. For the first time, the site will have a proper marker in memory of the victims.

Unfortunately, the present local government leaders, owing to political alignments, want to block the installation of these grave markers at the massacre site, despite requests from the families of the victims.

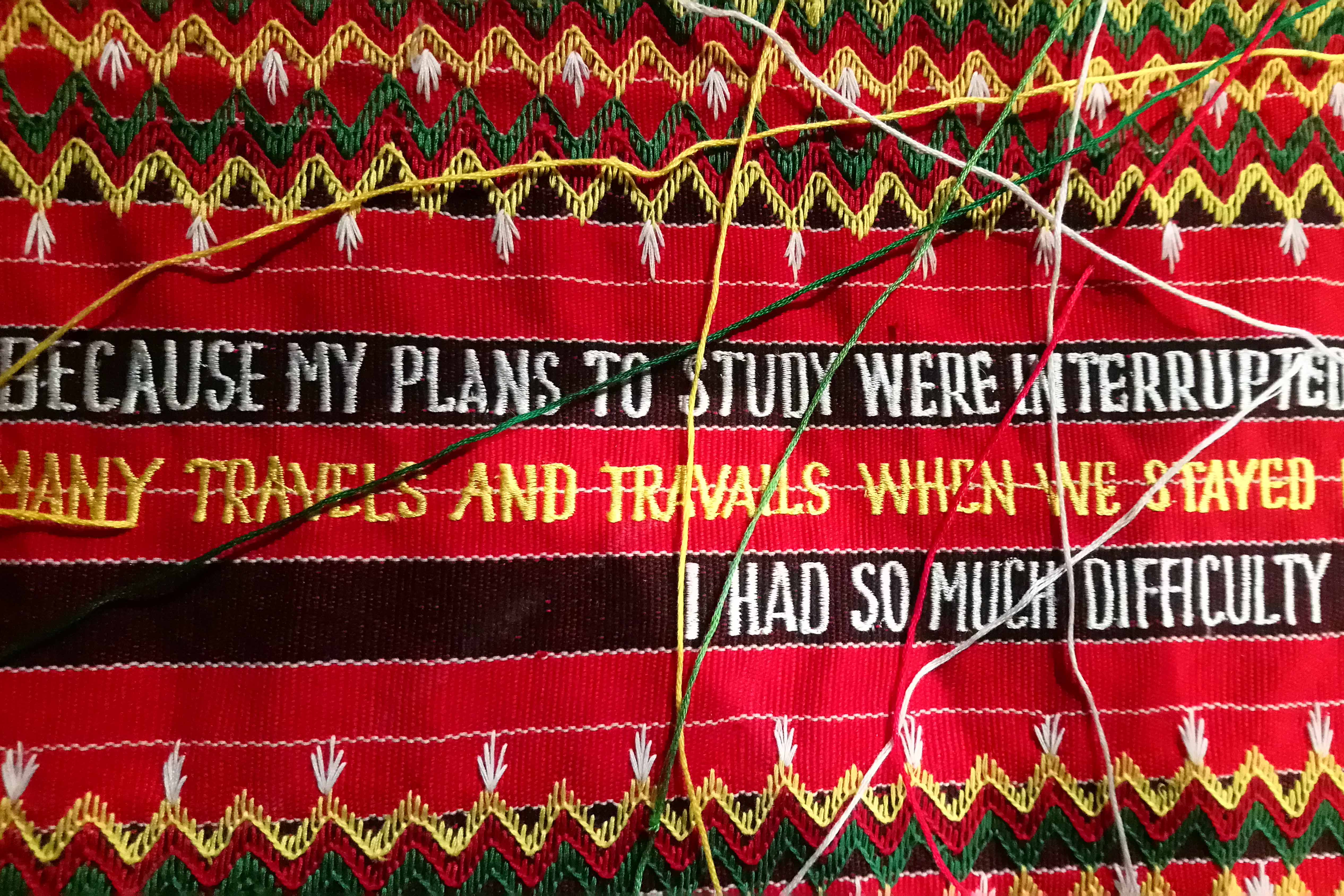

Traditional weaves stand side-by-side with their commercialized forms as the stories of women, in their mother tongues, and in English, are literally woven into the fabric: “Meanwhile, we were farmers … because my plans to study were interrupted.”

T’boli women faced not only the commercialization of their sacred, traditional weaving process but also sexually predatory male behavior from outsiders looking to include the Tboli in the cash economy.

There is even ephemeral art: sand pictures on the museum floor hearkening to the apparent erasure by fellow Muslims of Sama Islam given its syncretization of pre-Islamic spirituality.

Meanwhile, over the nondescript clothes of women-soldier-spies, a traditional canopy keeps watch, a tree-of-life print at its center. Not all of the words can be read, but that is part of the message.

All this coincides with the Philippines and United Nations’ National Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security, which started in 2017 and is slated to end this year. Also, WWWWW was created with the Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Commission in mind, formed by the Philippine Government and Moro National Liberation Front to study historical grievances to pave paths toward transitional justice.

When WWWWW first debuted, there was hope in the air for its creators and sources, and now, in its second run, the context is very different as some fear that the second Marcos presidency might repeat the worst elements of the first.

Boots Herrera, director and chief curator of the Ateneo Art Gallery stipulates that museums must “operate ethically with the participation of communities” following her discussions with the International Council of Museums in Prague, last August 24, during which the council also affirmed the need to redefine what a museum is in light of emerging social realities.

While men were massacred by bullets and gunpowder, women and children faced their own horrors, imprisoned as they were by state forces. Other women decided to join the fray on the frontlines, protecting their ancestral lands against the encroachment of state-sponsored greed.

What all stories have in common is the women’s continuing choice to recall, in itself a form of defiance in the face of historical distortion and denialism. This denial tragically extends to some of the very people oppressed and marginalized by policies and campaigns greenlit by the Martial Law regime of Ferdinand Marcos, Sr.

These issues remain largely ignored or denied in public consciousness, and the WWWWW exhibit is part of a bigger project memorializing and documenting these events and recollections. While WWWWW can’t hold all autobiographical details, these are intended to be published in an upcoming book.

Art has always had a shaky relationship with the culture surrounding it. Is art purely about aesthetics? Or should creators and audiences also consider the socio-political realities in which a work is created and later on, preserved and displayed?

Critical theory posits that a work is not created in a vacuum by a single, isolated genius, but is shaped by the socio-political and economic ideas of the society and era where the creators and viewers both live. Because of this, expounders of the theory like cultural critics Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault warn against fully believing artists’ statements on their work. Even Picasso in 1935 opined that “a picture lives through the one who is looking at it.”

The caveat of this viewpoint however has to do with works aiming to memorialize historical events whose loss or erasure may harm society, be it works about Martial Law, the Holocaust, or the Rwandan Genocide. In many contemporary works tackling such subject matter, no single artist takes sole authorship for the work, as demonstrated in the Ateneo Art Gallery’s current exhibit.

Given WWWWW’s collaborative process, the AAG deploys two sets of contrasting yet complementary approaches to art: individual vs. community authorship, and aesthetic vs. political judgment of a piece.

Works that have a more or less defined message clear enough to both audiences and producers, as well as clear in the historical context depicted, are aided by factors outside the production of the work, and these include curatorial decisions. Here, curators and their teams have control over elements that either clarify or obscure an exhibit’s message: lighting, spacing, and foot traffic, to name a few.

“A change in style,” the poet Wallace Stevens wrote, “is a change in subject.”

On that note, it’s easy to see why WWWWW needed a second run: its new elements make it more haunting, more beautiful, adding gravitas where needed, but also, when the heaviness threatens to burst at the seams, viewers are also reminded that these women live, and choose to speak and that there are still people choosing to listen, no matter the noise from those sinister sources determined to drown out their voices.

When the gunshots die down and tractor fumes dissipate, the ancient music – testifying to the beauty of man’s harmonious dance with nature – continues in Lake Sebu’s waters, Sulu’s seas, all the way to the Cordilleras’ grooves.

Did it ever stop to begin with?

Weaving Women’s Words on Wounds of War runs in the Ateneo Art Gallery until Oct 1, 2022.

When Pao isn't writing about art, he's trying to be a cat-whisperer