Walking into the exhibit space of Artinformal, one is greeted by the visceral, primal energy of red. Large red tapestries hang from the gallery walls, exuding an air of both the religiously solemn and the unflinchingly unnatural. These beating red hues might leave one apprehensive, as one so often is at the sight of bright red. Yet at the same time, they reveal hypnotic and familiar narratives that may appear strangely familiar.

In Namatanda, Doktor Karayom weaves an ode to the macabre and oftentimes cautionary nature of Philippine mythology. The term references the creature known as matanda sa punso, also known as nuno sa punso, a spirit that is said to live in small mounds. Violating their homes by kicking, stepping, or urinating on them would incite their fury, and they would place a curse on the offender, manifesting in mysterious bodily afflictions. The text for the exhibit, a poem, reads:

Nilagnat kinahapunan,

Nanginig ang kalamnan,

Nilamig at pinagpawisan,

Ang init ng katawan.

Namatanda is a tribute to both the forces beyond our control and the stories passed down from our ancestors that remind us that our actions, however blissfully unaware, can have consequences that fester deeply.

Doktor Karayom is known for his unapologetic and unfiltered imagery. His works are steeped in the uncomfortable and oftentimes darkly humorous. However, more than provoke, his distinct iconography reveals a keen perception of the framework of cultural, religious, and social webs that we share. Arrayed like religious tapestries, his works for the exhibit might induce a sense of reverence, their sizes evoking the presence of altarpieces. Yet we find that looking more closely upon these superstitions from our upbringings, reveals threads of creativity and ultimately, shared experiences.

Greeting viewers upon entering the exhibit space are two works in different shades of red, similar in shape to church portals. Hindi Pantay features a faint human figure obscured by a network of veins that pulse outward from the textile surface, stemming from a heart that appears to beat a deep red through the rest of the work. Around the figure are small hands suspended from strings. The hand is a ubiquitous symbol in Filipino culture – the hand in supplication, deference, or a hearty slap or pinch. No hand appears alike, for however it may gesture or whomever they belong to. Labas Pari oozes a more flesh-like tone. Small heads hang from gashes across what appears to be a mass of skin. The work instantly recalls pain, but upon closer reflection carries with it a sense of catharsis. Like the suspended hands, no two heads are completely alike, and they wrench themselves free of their fleshy prison. The gruesome stories we are told often shock and excite, and the horrors they birth are free to grow on their own.

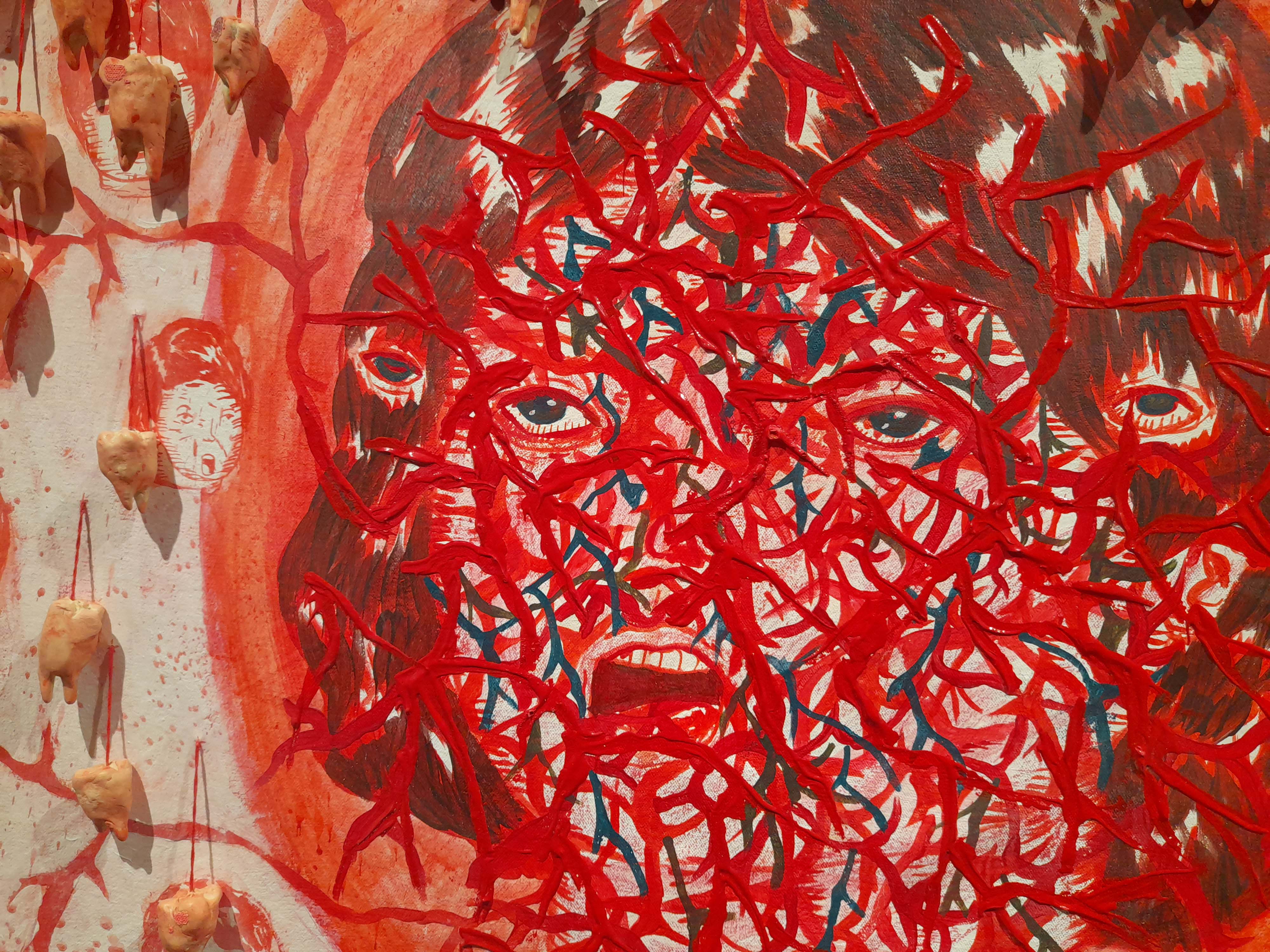

Each of Doktor Karayom’s works have different layers of visual depth, slowly enticing viewers to read even deeper. From his complex compositions to the three-dimensional elements that emerge from them, each piece yields a different perspective from different angles, reflecting again the idea of different facets from shared stories. These stories are on display in Padugo, Papawis, at Pamagat. The work depicts interwoven narratives of penitence and suffering. At the top center is the angered figure of Christ with a crown of thorns, overseeing a hellish landscape evocative of a Hieronymus Bosch painting. Yet like many Doktor Karayom works, it is overlaid with a tinge of dark humor. What appear to be clumps of fecal matter in red hang from the work. A grotesque addition to the bodily disfiguration on display, or perhaps a sarcastic commentary on the austere nature of Philippine superstition. Interpretations shift with each viewer’s eye.

In other works, supernatural entities are given form. Sayaw Usok depicts a wispy creature seemingly made of smoke. It gestures playfully, yet sometimes the mere suggestion of form is enough to unsettle the mind – a presence somehow felt, yet barely visible. In Mga Gabay na Walang Kamay, it is those hiding in plain sight that unsettle. A forest of figures with treelike appendages gathers in front of a large three-headed figure. Fragments of actual branches are tied to the surface of the work. Whatever religious implications the composition may bring to mind are instead seen through a more eerie, unnatural lens. The figure lording over its subjects seems to beckon viewers into a forest they may never be able to leave.

Namatanda carries meaning beyond its mythological associations. Younger generations, particularly those who grew up away from provincial areas, were no longer exposed to such superstitious tales growing up, and their cautionary lessons, lost. The exhibit text goes on to read:

Nangamoy matanda,

Galit ang salita,

Sa batang ang alam na gawin,

Ay matuwa…

Doktor Karayom’s works shine a light on a gap not just between age groups, but where tradition is remembered and has yet to be discovered. However the ancestral customs around the matanda sa punso may have dwindled, there remains the power of storytelling, whether through art or any other medium, to keep their spirits alive. For the evocative power of red flows deeper than blood.

Namatanda is on view at Artinformal Makati until August 20.

Mara Fabella is an artist, writer, and occasional fitness junkie. Tap the button below to buy her a coffee.

Images courtesy of the writer.