In the grim African proverb about a child burning down a village in order to feel the warmth of the embrace it was deprived of, the impartial nature of fire is portrayed in stark contrasts: as a source of warmth, and the spark of destruction.

Similarly, visual artist Iya Regalario mulls over the duality of fire in Tag-Apoy (“fire season”) — a new series of pyrography paintings on wood and ink drawings on paper on view at Pintô Art Museum until July 24, 2022 together with other recently-launched works by fellow female artists: Gaiang by Steph Lopez, This Isn't Mere Hyperbole by Janica Rina, and A Soft Place to Land by Celline Mercado.

The Promethean spark

Using fire as a central, almost intuitive element, Regalario ponders on its polarities — as both the warm glow of guidance and solidarity, and the primary agent of chaos, destruction and suffering in a perpetually burning pit. She uses it to reflect on her (sometimes unwilling) observations of the shifting tides of the Philippines’ cultural history and socio-political environment, as narrated in her latest body of works in three parts: three horizontal, scroll-like tableaus titled Sinilabang Kasaysayan, six individually-titled wood and ink portraits, and a four-part ink-on-paper vignette titled Bodies.

“Fire is life and death, the beginning and end, constantly burning through the timeline of our national identity as Filipinos,” says Regalario on the topic of the antiquity and persistence of fire throughout time. Sinilabang Kasaysayan reimagines some of the most memorable fire-born events and figures throughout the Philippines’ mythological universe, as contained in the myths and legends from across our islands. Among the collage of ancient deities portrayed are Lumawig of the highlands, the Great Spirit and Bontoc bringer of fire; Magwayen, the primordial goddess of the Visayan seas and underworld; and Bagobo god of war, Mandaragan, who is believed to reside in the dormant Mt. Apo volcano. The prehistoric gods appear alongside other figurative and literal depictions of notable events in Philippine history: from the arrival of Spanish colonial rule and the beginnings of the long road to revolutionary resistance in Sinilabang Kasaysayan I, the continued resistance to oppressors from within in Sinilabang Kasaysayan II, and the more recent literal and metaphorical scorched-Earth scenarios in Sinilabang Kasaysayan III. Having been finished not too long before the show opened, the third installation depicts events that have been, to our horror, continuing to unfold before our very eyes. Ending the last wooden scroll in flames, almost like both a cry of rage and frustration, and a precaution against pushing a collective threshold to its limits until it goes up in smoke.

The village is burning

In the same breath, the exhibit also delves into the destructive capabilities and symbolism of fire—forest fires, kaingin, effigies, territorial disputes, warfare, modern renditions of the crusades, burning people on stakes, and the dreaded return of fire-breathing tyrants.

“The element of fire is consistently represented in both its literal and symbolic senses to mark significant events in our history and to express personal ponderings towards the perpetually chaotic state of our nation as most notably stressed during the recent regime,” says Regalario.

Accompanied by an unprecedented physical replanting of her roots from Manila to Baguio City, the recent works also express the changes in the artist's physical and mental spaces molded by the pandemic. It continues in a similar direction as her past tarot-style portraits, while also taking off from that to delve deeper into specific personal and societal issues. While Regalario already had some of the works mapped out and in progress, the pandemic standstill had altered the course of some of the pieces, giving birth to portraits such as Higherlands, which attempts to make sense of her upland surroundings, its nuances, and her place in it; and the rhetorical Gulong Ng Kapalaran, which depicts Filipino National Hero, Dr. Jose Rizal, posing a recurring question that symbolically seems to point at more than one kind of collective illness and the corresponding cure.

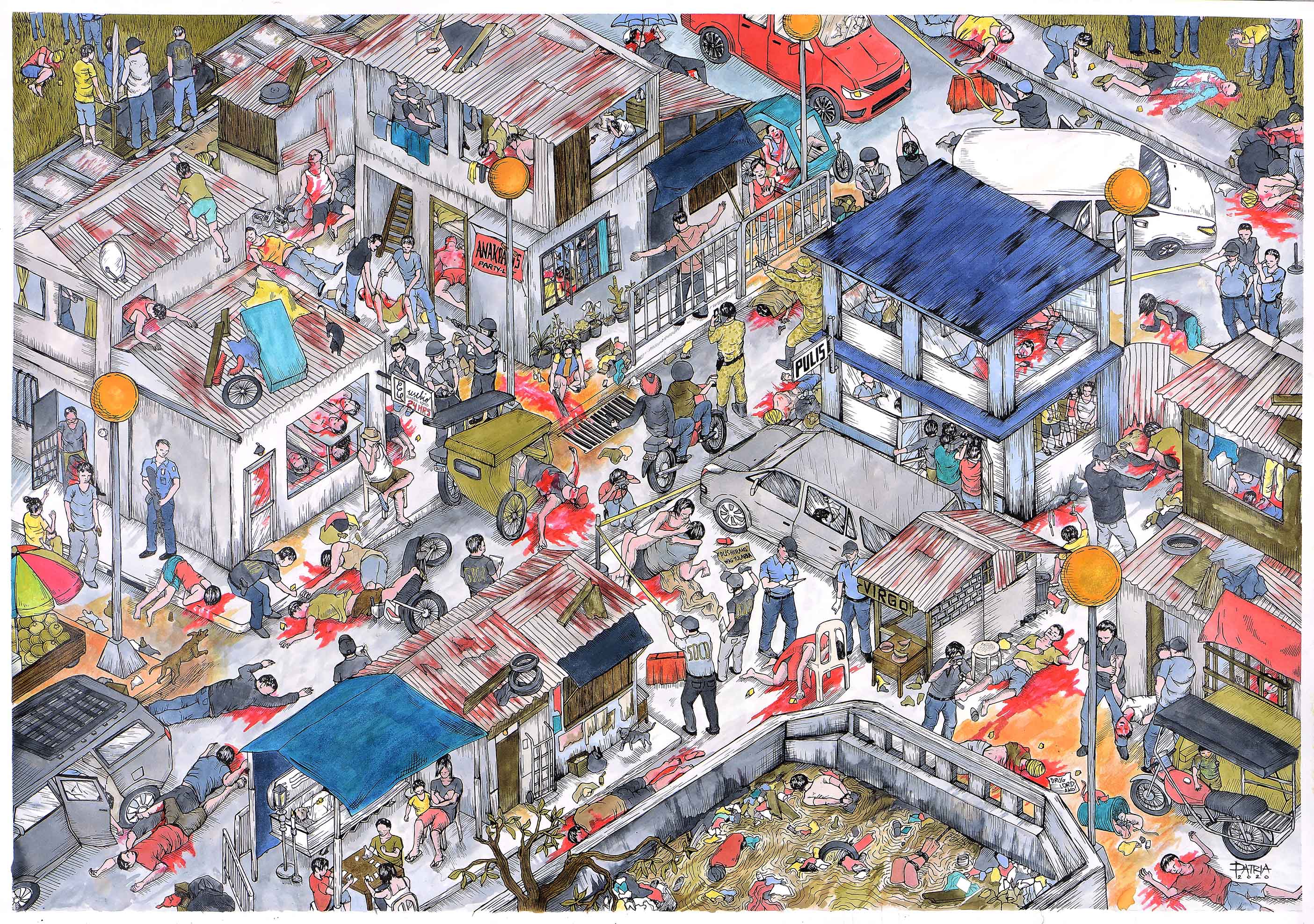

The more recent developments have also yielded Bodies, which takes an uncomfortable but necessary closer look at the casualties of a deeply flawed system whose cracks were made more pronounced in recent years. While the larger works on wood expound on the larger universe behind Filipino society and psyche, Bodies became Regalario’s subconscious coping and documentation of the times, zooming in on the real lives and warm bodies being crushed under the weight of the collapse—from the frenzied masses struggling to survive day-to-day during the pandemic lockdown, actual scenes of just some of the documented extrajudicial killings to date, and the gross contrast between the lives of the majority and the untouchables who remain unfazed by it all.

Huddle for warmth

With walls neatly painted in black and a pair of handheld torches perched by the entrance (titled Sulo, handcrafted by the artist using bamboo, as part of the show), the gallery space feels like a cross between a clandestine tavern and a welcoming space that offers refuge for the willing to safely view and digest some hard-to-swallow realities portrayed in Regalario’s personal documentation of the times. Like Regalario’s past shows, the works are laid out how she would exchange stories, heated discussions, and fears with loved ones in real life: honest, raw, straightforward, but always with some room for hope, warmth, and beauty.

In the words of Dr. Ma. Diosa Labiste’s exhibition notes titled Contagions of Repression and Frames of Resistance, Tag-Apoy may be the “antidote to the ambient despair” felt after the election polls, and this may be the nudge to confront our “losses, maladies, and ghosts using one of the few critical resources available to us: art”.

Combined with the all-too-familiar oversaturation of “violent online media culture, the proliferation of impunity and fascism, and the oppressive pandemic state imposed on top of an already severely disillusioned and freedom-deprived society”, Regalario sits through the duality of feeling driven to act in resistance and the dull helplessness of being a struggling, middle-class artist by looking back on fire as a necessary part of her weapon of choice—pyrography—and the meditative act of bringing ideas to life by using fire to draw on wood. While Regalario's main practice as a visual artist isn't limited to woodwork, her pieces for art shows seem to naturally gravitate towards pyrography on wood. Over time, the surfaces and scale of the canvases she uses evolve. Recent works also make more use of color, as her early works were more monochromatic and focused more on pyrography as a means of illustration. Currently, her works show a merging of her medium and styles. In Tag-Apoy, Regalario comes home, full circle, to the very essence of her craft. Perhaps, maybe because the uneasiness brought about by the current state of affairs can sometimes only be somewhat quieted by the continued act of creation and truthful documentation as an inextinguishable reminder that wherever there’s smoke, there’s fire, as there always has been.

Tag-Apoy is on display at Gallery 2 of Pintô Art Museum until July 24, 2022.

Nikki Ignacio is a writer and communicator who works mainly in public relations, media, science, art, and the development sector.