When you enter someone’s bedroom, you might be able to tell what kind of person they are based merely on their personal items and how they’ve been arranged. Most rooms have a vibe, a feel —even a smell —that conjures up an image of a person, whether or not you have met them. Bedrooms are where we rest, and so it’s where we find comfort. We wouldn’t keep something in our room that would disturb us. Synthetic Condition, curated by Carlos Quijon Jr., feels like a collection of items from different empty bedrooms. You get the feeling that these items are personal, but they feel removed from whoever it was that owned them. These are just things, but these are things that imply that someone was once there.

Entering the exhibit, the viewer is greeted by Tan Zi Hao’s You Again, a collection of rusty sculptures of the symbol Yòu, which means “again”. This play on words is a tired welcome; they are dilapidated remnants of the Self scattered on the floor. It’s you — but not quite. It feels like these objects were left there, abandoned and left to rust. It’s like returning to a place that’s not even remotely familiar anymore.

You Again, Tan Zi Hao, aluminum and stainless steel (2022). Image courtesy of the writer.

Beside You Again is a set by Ged Merino, titled Selecting Memory in Red. It’s a collection of mostly medical items wrapped in red fabric, sculpted to resemble various internal organs. These items, apparently, were used to care for the artist’s infirm mother. There is a visceral, emotional quality to Merino’s pieces, yet they also feel somewhat distant. The fabric may represent the tenderness of a memory. But fabric, as in articles of clothing, is also something you wear and eventually remove. In other words, although they can be part of the body, one does not identify with them. We are not our clothes; we are not our memories.

Selecting Memory in Red, Ged Merino, repurposed fabric on found and personal objects (2018). Image courtesy of the writer.

At the end of the room is Jao San Pedro’s A Fold in the Horizon, which is a set of felt sheets with markings. There is also a video of someone dancing. They are wearing sheets of clothing in no discernable fashion, moving around in a manner that doesn’t feel inwardly motivated. It feels like they are being moved mechanically. They are hollow movements. The felt sheets are markings from the dancer’s movements. It feels like it’s just proof that someone was there, but nothing more.

A Fold in the Horizon, Jao San Pedro, video and friction on felt (2022). Image courtesy of the writer.

A Fold in the Horizon brings to our attention the way we make meaning out of the echoes of our mere existence, expressed through movement. Following the psychic mechanism of the world around us, we often move like automatons. Without realizing it, we transform and then leave objects behind. These things that are us but not quite; things that are clues to what once passed a space.

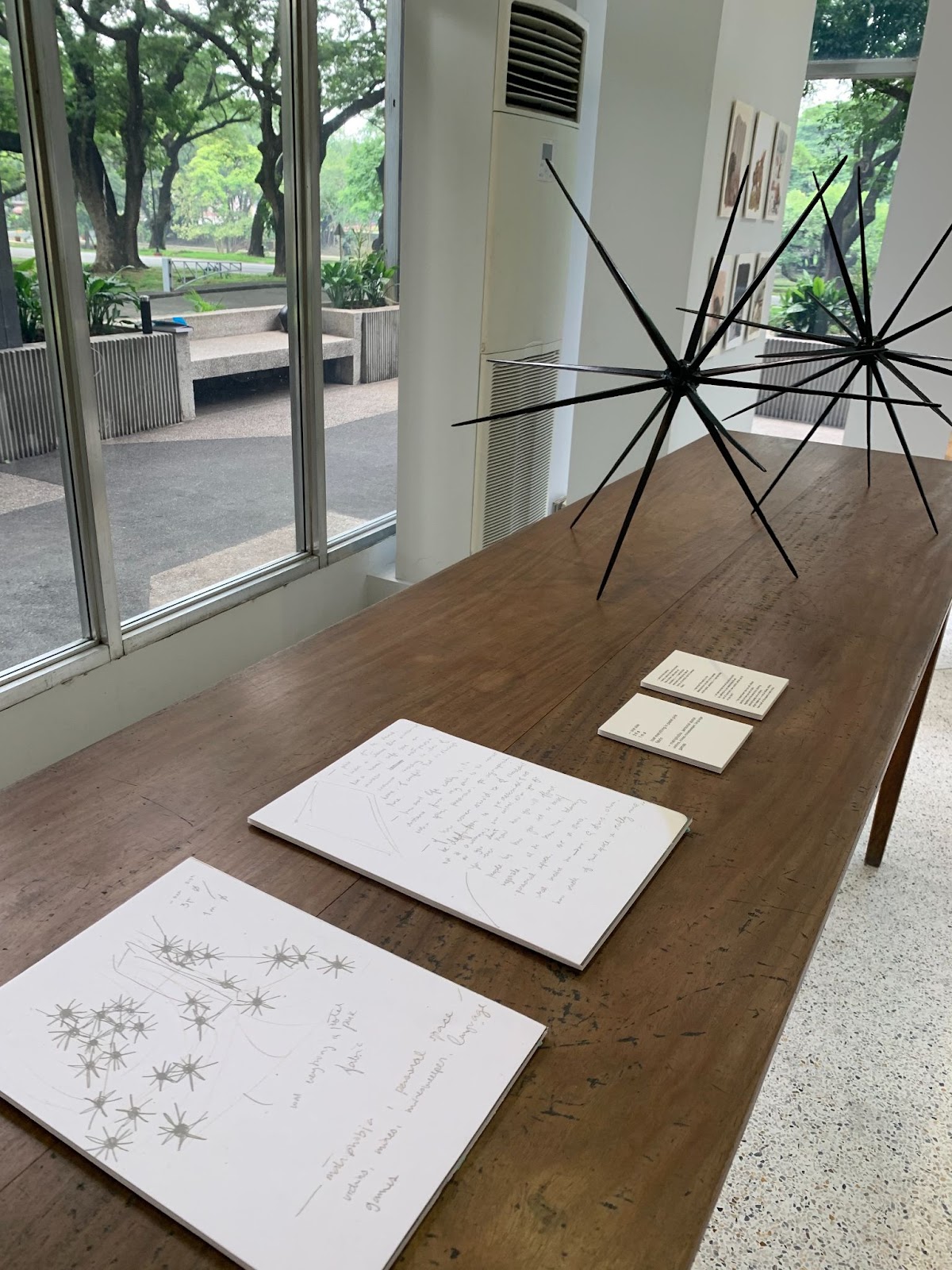

The exhibit extends to the other side. There are more video installations and other personal items. For example, there are reproductions of journal entries alongside spiked sculptures. Bree Jonson’s work, Urchin Studies, is a glimpse into what Jao San Pedro’s work suggests. Urchin Studies presents the inner mechanical system that transforms inspiration into works of art. The journal entries show scattered thoughts surrounding an idea — ideas about ideas. The human mind is a meaning-making machine, but a machine nonetheless.

Phuan Thai Meng’s prints feel intentional but not quite; it’s as though they exist between the inner subjective world of dreams and garbled images, and the external objective words of logic and clear symbolism. They are the images that appear between sleep and waking consciousness, when things don’t quite make sense, yet are full with meaning. There is a context to these pieces. There is a story and a memory attached to it. But without anyone to tell these stories, the viewer is left to guess. Nevertheless, even guessing is a natural process of the human machine — by being there, being surrounded by these pieces, the viewer leaves behind a trail of meaning.

When a statement is synthetic, that means it must still be verified. In other words, its truth lies in how the statement interacts with the real world. This is in contrast to analytic statements, which are self-evident; the truth lies in the statement itself. Synthetic Condition shows you synthetic statements in the form of tangible items. They carry psychic weight, but this weight is implied, and not said outright. Walking around the exhibit, one might feel at peace. Yet, one might also be oddly uncomfortable with the idea that, without being fully aware of it, these items are actually raw and vulnerable expressions of inner worlds.

The items that surround us are incidental to our basic human-ness. In other words, they are there because they represent fragments of our identity. They may have been created with a particular intention, but only because it’s our nature as humans to create. We project onto the objects of the world our psychic experiences, such as our memories, emotions, and perceptions. We give things meaning, because we are meaning-making beings. However, the items are not us. They are disposable extensions of us. It’s like a snake shedding old skin: it’s what they are, but not quite. Synthetic Condition can feel like a cozy collection of implications, doorways to various bedrooms. Scattered around the exhibit are personal effects. They are subdued totems imbued with deep, musty, and emotional psychic energy. They have been transformed into important relics by the mere virtue of being touched by a human being.

Synthetic Condition features Au Sow Yee (Taipei), Allan Balisi (Manila), Nadiah Bamadhaj (Jogjakarta), Chan Kok Hooi (Penang), Chong Kim Chiew (Kuala Lumpur), Sam Feleo (Manila), Joseph Gabriel (London), Bree Jonson (Manila), Celeste Lapida (Manila), Ged Merino (New York/Bogota), Jao San Pedro (Manila), Hà Ninh Pham (Hanoi), Phuan Thai Meng (Kuala Lumpur), Tan Zi Hao (Kuala Lumpur), Yim Yen Sum (Kuala Lumpur), and Ev Yu (Manila). It was created in partnership with A+ Works of Art in Kuala Lumpur. It is available for viewing on the ground floor of the U.P. Vargas Museum until 25 June 2022.

Carl Lorenz Cervantes likes Negronis, psychoanalysis, and the occult.