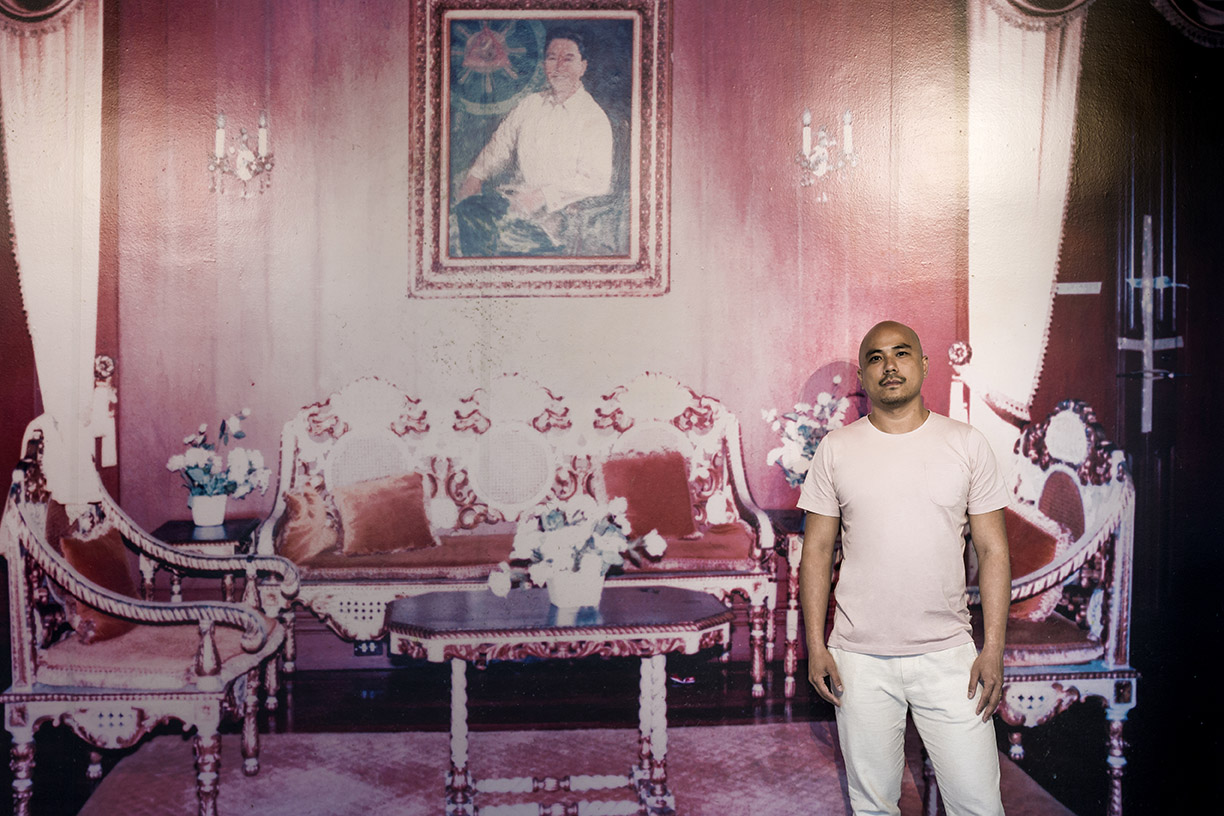

The artist, Pio Abad, by a large printout of the Marcoses’ private chambers in Malacañang. The image lies near the entrance of the exhibit.

On the eve of the upcoming and arguably most important presidential elections to date, Pio Abad reminds viewers of the ghosts that still haunt the halls of Philippine history in his solo show “Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts” at the Ateneo Art Gallery.

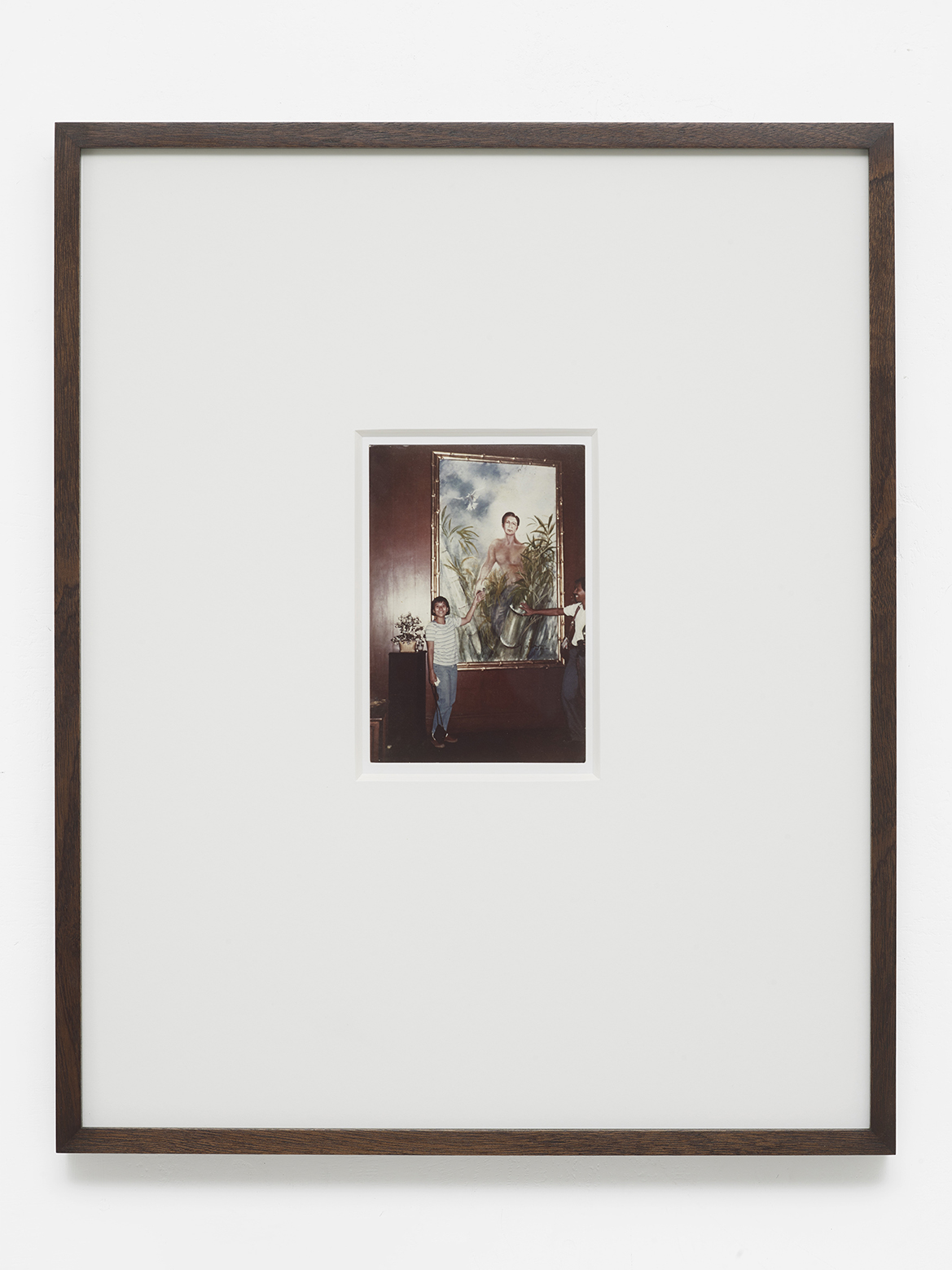

Following the Marcos family’s expulsion from Malacañang after the fateful EDSA Revolution of 1986, waves of protesters began to storm the palace. Among them were Butch and Dina Abad, then student activists, who only a few years prior had been detained by the military for their community work. Within the Marcoses’ private chambers, the Abads, along with Corinna Araneta, take a photo by a life-size portrait of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos, depicted as the mythical Malakas. Smiling cathartically, they reach their hands toward the painting, belittling and dispelling the myth of power for what it truly was — an imitation.

A photograph taken by Dina Abad of Butch Abad and Corinna Araneta by a portrait of Ferdinand Marcos on the day of the EDSA Revoution, February 25, 1986.

This photo marks the beginning of the many histories unpacked by Pio Abad in his solo exhibit, Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts at the Ateneo Art Gallery. This show marks the culmination of ten years of research by the artist into the Marcos dictatorship, continuing the commitment to justice began by his parents decades ago. Abad calls this show an “epic undertaking,” and rightly so, as it lays out the insidious threads of corruption spun by the Marcoses that continue to be woven years after their downfall. Employing a variety of materials and techniques, Abad lays out photographs, texts, visuals, and recreations that attest to the crimes committed by the conjugal dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. With minimal overt intervention, he presents these stories in a direct, inventory-like manner so their truths appear plain for all to see. “Either it’s an art exhibit as a history lesson, or a history lesson as an art exhibit,” Abad muses.

Malakas and Maganda. Painted over reproductions of the portraits of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos as Malakas and Maganda. Next to it, a video documenting the painting in black.

The show begins by shedding a light on the Marcoses’ appropriation of the fabled Malakas and Maganda of Philippine folklore. Following the photo taken by Abad’s parents and Araneta are two paintings covered entirely in black. The Marcoses commissioned portraits of themselves fashioned after the mythical characters: Ferdinand as Malakas and Imelda as Maganda. Fabricating an illusion of strength and beauty, the Marcoses weaponized the well-known myth in order to serve their own ends. Abad had these paintings reproduced by a folk painter and subsequently painted over in black by a museum technician. The act, Abad says, is a form of erasure to combat the erasure of truth the Marcoses espoused. At the same time, it also signaled an act of protest. The works were initially exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design in 2016, the same year when, despite widespread opposition, the Duterte administration allowed Marcos’ remains to be buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani. The black paintings, simply titled Malakas and Maganda, were a cry of protest, but at the same time, one of despair, of “not knowing what to do.” Years after the burial, the statement, all in black, remains just as potent.

A life-size replica of a study of the Marcoses as Malakas and Maganda, sculpted with concrete and steel by Abad.

Alongside the reproduced paintings is yet another reproduction. A life-size concrete sculpture of Malakas and Maganda stands near the center of the room. The artist created the work based on a smaller sculpture he believed to have been made by sculptor Anastacio Caedo. The model was likely a maquette for a monument to be made for the Marcoses. Abad later discovered that the Caedo maquette was an unauthorized fake. His own iteration of the sculpture stands as a monument to this cycle of forgery. “Counterfeit myths seem appropriate to a counterfeit presidency,” Abad observes. His counterfeit beckons viewers in from outside the exhibit space into the room dedicated to myth — a space as dim and hollow as the Marcosian myth of strength and beauty had revealed itself to be.

The next section of the exhibit highlights the vast amount of wealth accumulated by Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos under the aliases Jane Ryan and William Saunders. These were the identities they used to create confidential bank accounts in Zurich that, by the time they were ousted from power, had amassed approximately $10 billion in stolen wealth from the Philippine government.

Forty giclee prints, made to scale, of the forty pieces of Regency-era silverware that broke the record for the sale of silver in a New York auction in 1991.

In a brightly lit room, the Collection of Jane Ryan and William Saunders is laid out opulently for all to peruse. Forty prints of decadent silverware printed out to scale, feature the record-breaking collection of Regency-era silverware acquired and later abandoned by the Marcoses at Malacañang. The pieces in total sold for $4.9 million.

Twenty-three ink sketches by the artist of the lost items of the Samuels collection, later recovered in the dwelling of Irene Marcos.

On the opposite wall are a series of twenty-three ink drawings by Abad of the lost items from the Leslie Samuels collection. Ornate furniture and priceless figurines are drawn in meticulous detail in a graphic, linear style, described as “cartographic.” Detail is crucial for Abad, as the topographic contours of each drawing metaphorically map out the narratives of displacement and theft each object underwent as part of the larger histories traced by stolen Marcos loot. These artifacts were originally to be auctioned off at an apartment in New York along 666 Park Avenue (“You can’t make this up,” Abad jokes), before a mystery buyer purchased the entire collection for nearly $6 million. The pieces were eventually found at the home of the youngest Marcos, Irene, and her husband. Ironically, it was Rudy Guiliani, then a U.S. attorney and now accused of fraud himself, who indicted the Marcoses after the stolen Samuels collection was recovered.

Postcard reproductions of ninety Old Master works implicated in the Marcoses’ fraud, some of which are yet to be found today. At the back of each postcard is a unique text detailing the accounts of the stolen paintings. Visitors are encouraged to take the postcards for themselves.

Abad has always had an affinity for inventories and archives. His first museum experience was at the Malacañang Museum, where he was able to view an archive of the stolen items left behind by the Marcoses. For Abad, there is a physical and visceral aspect in going through an inventory. In laying out his pieces this way, he evokes these qualities among a simulated inventory of riches that, for the most part, seemed almost intangible in value, and thus the theft, easier to underestimate. He presents massive, inconceivable amounts like $10 billion in more concrete, quantifiable ways. In allowing his audience to walk through and more closely engage with each work, he invites reflection and discussion. Between the Samuels and Regency collections is a series of ninety postcards depicting ninety Old Masters paintings acquired fraudulently by the Marcoses. At the back of each postcard, a unique text — excerpts from news articles detailing the paths of corruption the paintings have traversed. Abad not only encourages viewers to read each postcard but to take it with them. Allowing the public to reclaim these works in a sense serves as a form of restitution, democratizing a collection of invaluable artworks the Marcoses sought to keep for themselves. The use of postcards is almost ironic — cheap, easily reproducible — artsy souvenirs of sorts, relocating the works to memories. At the same time, tokens of travel for some artworks yet to be recovered.

Replicas of the Hawaii collection of jewelry by, reproduced by Abad and Wadsworth. The caption for each piece details their monetary value in terms of national development lost during the Marcos regime.

The most labor-intensive and arguably most confrontational of the works from the Collection of Jane Ryan and William Saunders are the jewelry replicas of the Hawaii collection. A collaboration between the artist and his wife, Frances Wadsworth Jones, the series of twenty-four models represents the jewels smuggled by the dictator and his wife into Hawaii in 1986, amounting to approximately $21 million. The pieces were meticulously reproduced from documentation from the Christie’s auction that would supposedly extradite the wealth back to the Filipino people. The auction was abruptly canceled when Rodrigo Duterte was elected in 2016. The research was done by Abad while Wadsworth Jones, a jeweler, created the 3D-printed replicas. Sections of each model were left blank where details from the available resources were insufficient.

“52,631 teksbuk para sa mga estudyante sa ikalabing-isa at ikalabindalawang baitang.” ("52,631 textbooks for students in the 11th and 12th grades.")

It was important for both artists that each piece be rendered without color, so that, echoing the title of the exhibition, the works appear to be ghosts, bearing an entrancing beauty on their own, while still becoming shadows of the real jewels that remain locked away from the public. But perhaps the most ghostly aspect of the works lies in the subtext. The works are placed on plinths, with each replica captioned in both Filipino and English. Instead of the usual description, however, the caption for each model relates the value of each jewel with its corresponding amount in national development, similarly lost as ghosts during the Marcos regime. An ornate crown reads, “Pabahay para sa 1,200 benepisyaryong walang tahanan” (Housing for 1,200 homeless beneficiaries). Pairs of decadent earrings, “Ang karaniwang taunang kita ng 15 Pilipino” (The yearly wages for 15 Filipinos).

The title Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts comes from Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, a text that proved seminal for the activists of Ateneo de Manila University during Martial Law. In the work, Freire says, “Fear of freedom, of which its possessor is not necessarily aware, makes him see ghosts. Such an individual is actually taking refuge in an attempt to achieve security, which he or she prefers to the risks of liberty.” The confrontation of works like the jewelry collection lie not in overt imagery, but in the explicit communication of facts — facts that even the staunchest of critics would be hard-put to deny. The artworks on display are quite removed from the bloody images that may have been expected from a depiction of Martial Law. On their own, they are refined, beautiful, and dignified. Yet the historical contexts of each work beg the question, is such comfort and security worth the risks of liberty? For Abad, Freire’s text and this exhibit serve as a call for people to educate themselves: a “seduction into reading history and politics.” “At a time when fact is a battleground, you need to excite people to look at fact,” the artist says.

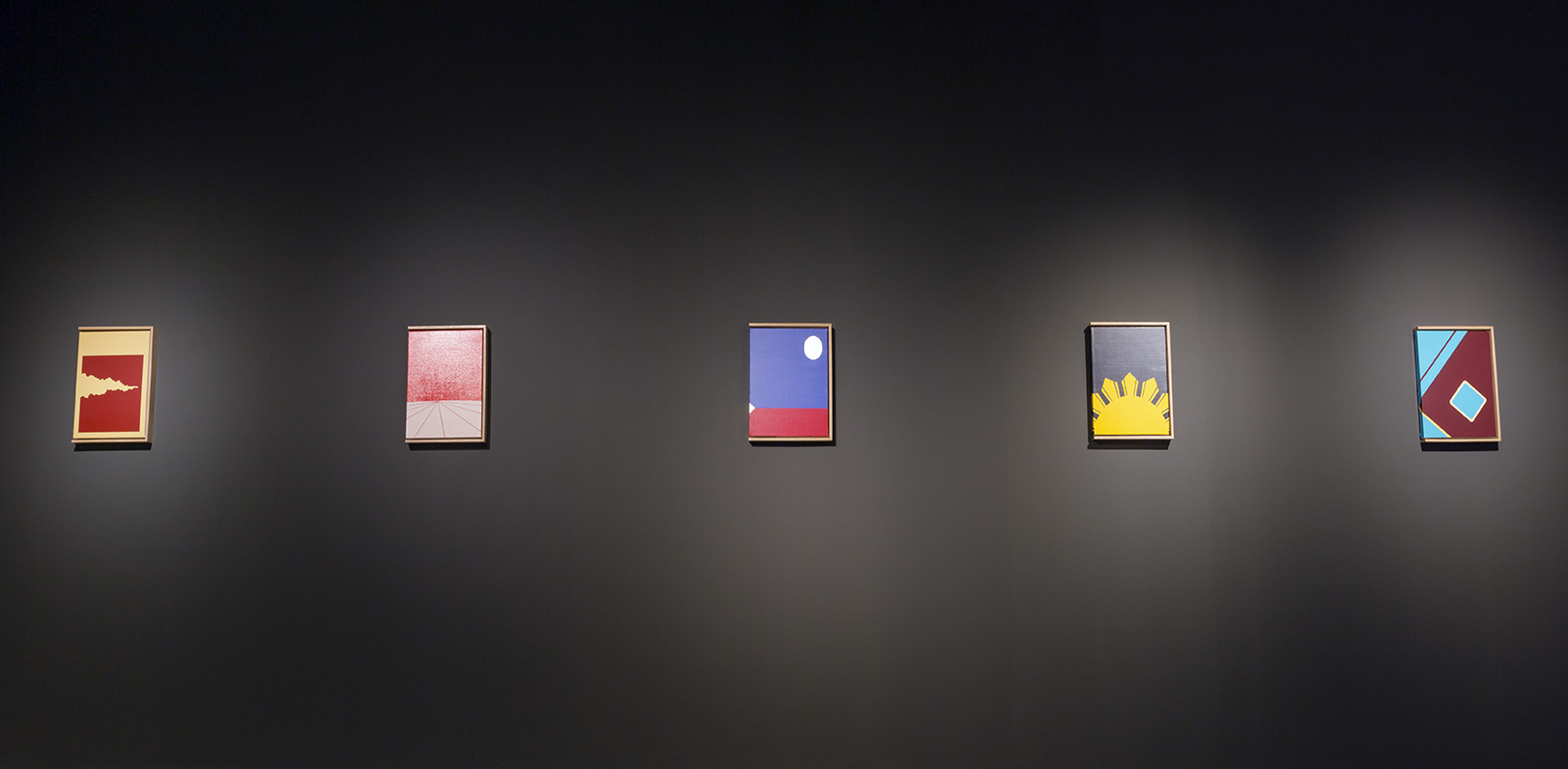

A series of memorial paintings appropriating designs from Marcos manifestos, turning them into tributes for fallen human rights defenders and victims of Martial Law.

Left to right: For Archie, For Bobby, For Karina, For Dinky, For Evelio.

Not wanting to allot more space to the Marcoses, Abad devotes the last series of works to those who fought against their cruel regime. A series of fourteen small abstract paintings line the walls of the space. Their titles: For Noel, For Bobby, For Archie, For Evelio, For Jesse. For this series, Abad took the designs of Marcos manifestos and stripped them of all text, erasing their claims to power. The first two works in the series, For Silme and For Gene, are in honor of Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes, leaders from the Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino, who were murdered for leading the fighting for justice in the U.S. and the Philippines. Their killings were eventually linked to transactions in the U.S. by the Marcoses for what were labeled, “special security projects.” In dedicating these paintings to activists, community organizers, and leaders who were victims of the Marcoses’ cruelty or gave their lives opposing it, Abad transfers the supposed authority of Marcos propaganda to those who held the true power to lead. Many of these figures were family friends of the Abads. The artist views this ongoing series of works as a “productive process of grieving” for what the nation has lost and what he has lost personally. The last two works are titled For Dina I and For Dina II for Abad’s mother, who passed in 2017. These paintings symbolically close out the years of history on exhibit, starting from the photo Dina Abad took herself back in 1986.

Years after the Marcoses were overthrown, much has seemingly changed and stayed the same. Across the period of its conception, this project has been witness to many of these events: the Presidential Commission on Good Government’s raid of Imelda Marcos’ offices, Ferdinand Marcos’ burial, and now most timely, the upcoming 2022 presidential elections, as a Marcos attempts yet again to return to power. Abad and Boots Herrera, director and chief curator of the AAG, had always planned for the show to release before the elections, but never did they expect it to be as relevant and needed as it is today. As a tidal wave of fake news and historical revisionism seeks to erase the Marcoses’ bloody legacy, the facts stay the same — the wealth still missing, the damage dealt, the lives lost. “By rendering things as art, it makes things solid in some ways,” says Abad, clad notably in pink for the show’s opening. Months from now, regardless of the outcome of the elections, the exhibit will still be on display at the AAG, and the narratives of corruption and bloodshed will remain. Yet so does the hope that this exhibit and the stories it tells, shaped by the context of the days to come, may be viewed from the lens of victory against the ghosts that have continued to haunt the country.

Pio Abad’s Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts runs from April 19 to July 23, 2022 at the Ateneo Art Gallery.

Images courtesy of the Ateneo Art Gallery.

Mara Fabella is an artist, writer, and occasional fitness junkie. Tap the button below to buy her a coffee.