Ciane Xavier’s new exhibit, “Connecting and Disconnecting”, opens a portal into a bizarre and uncanny domain. Our perception of the physical — our bodies, the world at large — is distorted through the lens of technology. In a bright room, we see warped images of odd bodily proportions, beasts and robots. White sculptures with blank eyes and vacant gazes stare at nothing. Black butterflies rest on the walls. On the floor are bodies engulfed in black eggs with rubbery shells, surrounding a larger sculpture of a woman in the center of the room. This piece is titled Mother; her enlarged, disproportionate foot is extended, almost in a dance. The exhibit is interactive. The art seems to be making a point about how our perception of our own human body is the key to reconnecting with reality. QR codes accompany some of the sculptures, which access a scene of figures walking on water and butterflies emerging from this ethereal, cosmic ocean. (Fittingly, as we contemplate the effect of technology and the internet on our ability to perceive and appreciate reality, we are asked to be constantly on our phones.) The harried paintings, in black, red, and white, showcase naked bodies hairy and menstruating. A block of a different color, present in all of them, feels out of place. The painting We features two figures, facing each other and reaching out, almost touching. There are also two blocks behind each of them. This may represent their disembodied soul, trapped in the emptiness of a distant screen, longing to connect.

Some pieces are supplemented with audio playback, triggered by motion sensors. One is Reflection, a sculpture of a naked woman wearing a rabbit mask, with her tail in front. The words repeated are “My reflection, my reflection”. This reflection is a hazy, wavy image on an LCD screen. Across the room, the sleepy voice of Alan Watts plays over and over again, reminding us that what we do is what the universe is currently doing, here and now. There, a masculine figure is reaching out to the LCD screen where Watts is speaking. The image on the device is the floating head of the same figure, its body submerged underwater. The sculpture, titled I see you, hesitates and seems to quietly wonder: should I turn the device off? If I do, am I also switching myself off? The screen itself is a mirror: but are we watching ourselves, or are we being watched? Who is watching? One suggestion, a thought that springs from the Alan Watts audio, is that the universe humans--“human” is here used as a verb, something the universe does. It isn’t so much that the universe “populates” the world with human beings, but instead that the universe itself exists and can be identified through our being human. By existing--that is, by being conscious and mindfully aware--we participate in this cosmic act, and we human as the universe humans. Further, although we have gotten used to seeing ourselves as individuals, we are all multiple waves of the same ocean, different breaths of the same lung. Locating Watt’s idea of metaphysical connectedness in Xavier’s art, we see that our relationship with cyberspace, and the fragmented identities we create through it, all exist and are part of one cybernetic astral plane, from which all things emerge. If we follow this rabbit hole, we dive headfirst into wondering whether we’ve created our own parallel universe through technology. Does our technology people (“people” here, used as a verb)? If so, did we create technology, or does our sense of self, in fact, spring from it?

Extricating ourselves from that philosophical spiral and grounding ourselves back in reality, we might begin to notice something more straightforward, but just as important to consider. Beyond technology, the exhibit seems to also be drawing from the experience of being a woman, and what it means to be one. Study 5, a painting of a woman with her legs up and exposing her vagina, has a sensor that asks, “Who are you?” in different tones: consenting, confused, intrigued, and afraid. Engaged with the nude, the works question, if at least unconsciously, the awkwardness one might have toward the female body, whether as witnessed or as possessed. Beyond the physical, the exhibit seems to also make a statement about how the woman positions herself. Mother, the largest sculpture at center, depicts a woman with huge feet. Maybe this size of feet is required, to be a strong foundation for the female body it supports, and the role it has to play.

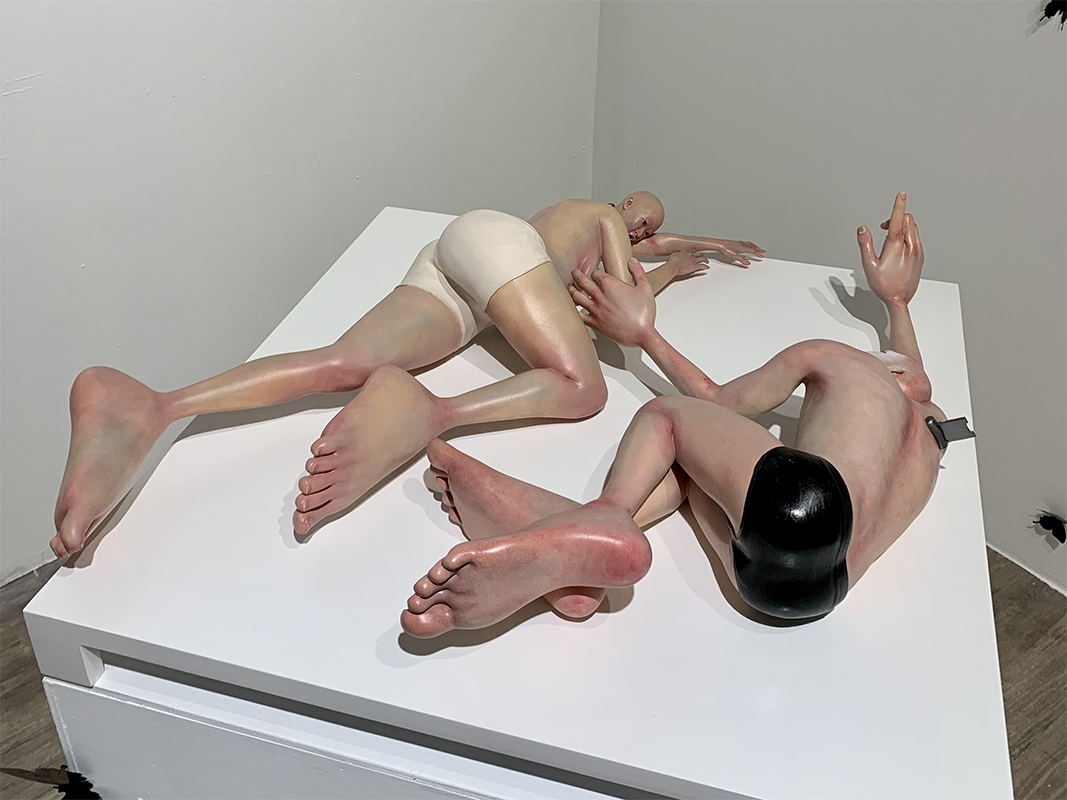

Towards the end, the figures seem more exhausted. In Dragging Away, the sculpture is being pulled by a black butterfly. It suggests that technology drags us around, and we let it. Cyberspace is mesmerizing; it is easy to get lost within it. By interacting with it, we become it. We merge with this digital universe and create ourselves over and over again, through the varied identities we've constructed online. We’ve overstimulated ourselves through technology, creating worlds within worlds, and we’ve fragmented ourselves to achieve the illusion of omnipotence, to the point that there’s nothing left of us. Are we creating the experience, or is it being created for us? Finally, in Together, the only fully colored sculpture, we see an attempt to make a real bodily connection. But the figures seem too drained.

‘Connecting and Disconnecting’ invites the audience to contemplate on their own human-ness. It may not be too late to remove oneself from the simulation, but what are we leaving behind? Who are we leaving behind? Do we transcend our own human-ness by leaving cyberspace, or are we simply rediscovering our truest selves? Further, who is the truer self--the one that was born or the one was created? These questions, which might be philosophically overworn, regain a kind of newness, as though we were confronting them for the first time. The screen has been switched on — or is it a mirror?

The exhibit will be up at Art Cube until October 9, 2021.

Carl Cervantes likes Negronis, psychoanalysis, and the occult.