In the latest paintings of Pepe Delfin, the viewer's eye tends to move about them as their inhabitants do, hovering from place to place, between wakefulness and sleep. The gaze softens as it goes along the flat planes, easing in with the afterglow cast upon what appears to be a somnambulant, placid city.

Depicted amid the city's confounding architecture are the equally confounded vagrants, whose almost nonverbal apprehension begins with the first work past the gallery's front room door, aptly titled What's Going On. A similar sentiment is sounded throughout the other canvas pieces: the geometric shapes proceed by mute permutation; yet, in whatever way the shapes rearrange, the predicament remains the same. The works' titles, too, (From an Old Memory Something Follows, It Feels Like Something, Something's Coming, There's Something About this City) add to the frustrated disposition – that there is something incipient afoot, and that it would, any minute now, come fully into view.

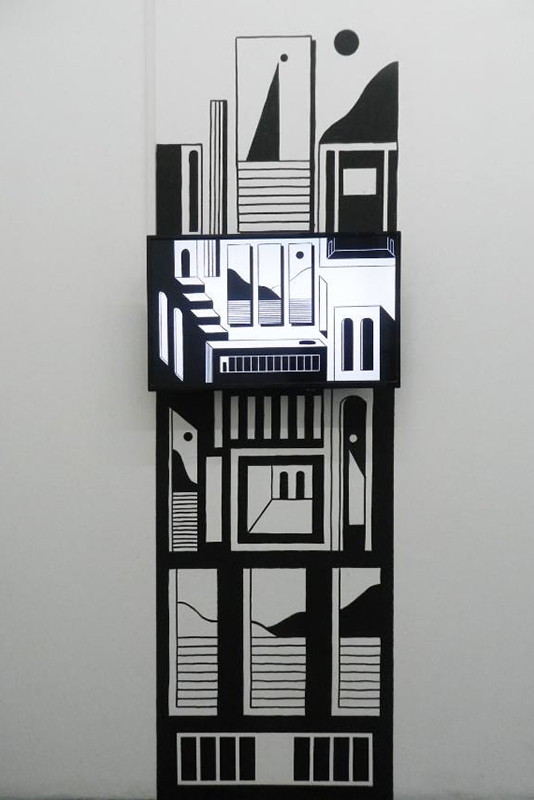

But nothing quite does. If you had gone the natural course for the exhibit – from left to right and back to the door – the last piece you'll see is an untitled video work, screened from a television mounted center of the wall, with a painted mural of similar design extending above and below it. Introduced in the video is a dot – presumably, "Dotty," the artist's recurring character – caught in a continuous loop. Not once does the animation cut from the still vantage point of the domestic interior, and, for 75 painful seconds, Dotty hovers, slowly down the staircase at first, then glides anxiously across the space, bumping against the walls and into the various entryways, each of which transport it to a different area of the same place.

Dotty performs all these with the same frantic energy by which I am writing this. So Dotty is, in my bias, attuned to the deeper rhythm in-step with what is sensed in most things today: restlessness, to an insomniac degree, from the fact that time is unhitched. There's some consolation here to find that it's not just us; all of it is drift: above the underlying pattern and shapes, their attendant Euclidean logic, and the spaces in which Delfin's vagrant figures find themselves in, all appear swept up in that slowed, perpetual movement without grist.

The inflection point occurs in the Uneasy Lies All the Heads series, which trades the solid plates of color and percolated tonal light for a smokey effect, due, in large part, to the change in medium: watercolor on cotton rag. Here, the settings are less compact, more navigable, less labyrinthine. And where the previous works might critique external forces, presented instead in this series are unreproducible, interior states, the structures of mood. While the figures still evoke the sense of an expatriate, they don't seem nearly as arrested as before, pacing or perching themselves along the edges (I, II, VI) or laying in repose (III).

I want to say I share the wish for the clarity these stick-limbed refugees quietly appear to have redeemed, but that is beside the point. It's more the bathed atmosphere of longing that does it, seen best in the émigré figures' bowed heads and, frankly, in the eyes of anyone that has had trouble adjusting to what's been on the news. It's the kind of longing after coming to terms with the fact that all one could do would never be equal to what is needed; that one's wins are never quite to scale; that acting transformatively in the world, to be further consequential, remains still a possibility; and that is the root of the hurt. Realized in Delfin's abstract, distilled world in miniature, the desire and appetite for changeability can be part and parcel, too, with sly, capitalist programming. Whether or not it is to a ludicrous end, interest is how things continue to move.

Against such functional pragmatism is the patient response, the smallest choice makable. One could, recalling Walter Benjamin's The Arcades Project, take stock, or, to no 'real' failure, withdraw. The act doesn't advance a proposition outright, but in a time when one can't rest without proper resolution, 'Heavy Lies the Head' asserts a core modesty. And loneliness, like art, like architecture, asks to be witnessed, if at least at an oblique angle – and at the exact degree and moment it recedes from view.

.jpg)