Not Visual Noise remains scheduled to be on view until March 29, 2020, in the Soledad V. Pangilinan Arts Wing of the Ateneo Art Gallery. Curated by Angel Velasco Shaw, the exhibit is both a contemporary survey of Philippine photography and a remarkable assessment of the practice in a world that wouldn’t have thought to need it.

“What is the role of a photojournalist, documentary and contemporary photographer, and multimedia artist in a media-saturated world? How do these creatives represent the social and cultural issues that concern them?”

In Shaw’s accompanying essay, “media-saturated world” reads as a tell-all, which, beyond the familiar scare large statistics brings, hardly warrants further explanation. And while images like “torrent of media” or “being inundated” may come to mind (they fit well with the running staples, “mainstream,” “web surfing”), they don’t lend much to what we invariably imbibe. The world is indeed media-saturated; it’s also data-driven.

Through third-party cookies, limited ad preferences, all those under the catch-all term, “algorithm,” visual culture does not go unparsed. Each tug of a scanning eye or thumb-scroll communicates within a feedback relay that indiscriminately eschews one novelty for the next. Against such recursion, in the grand scheme of the digital every day, underwritten in Not Visual Noise is the haunting implication of an amnesiac state of mind.

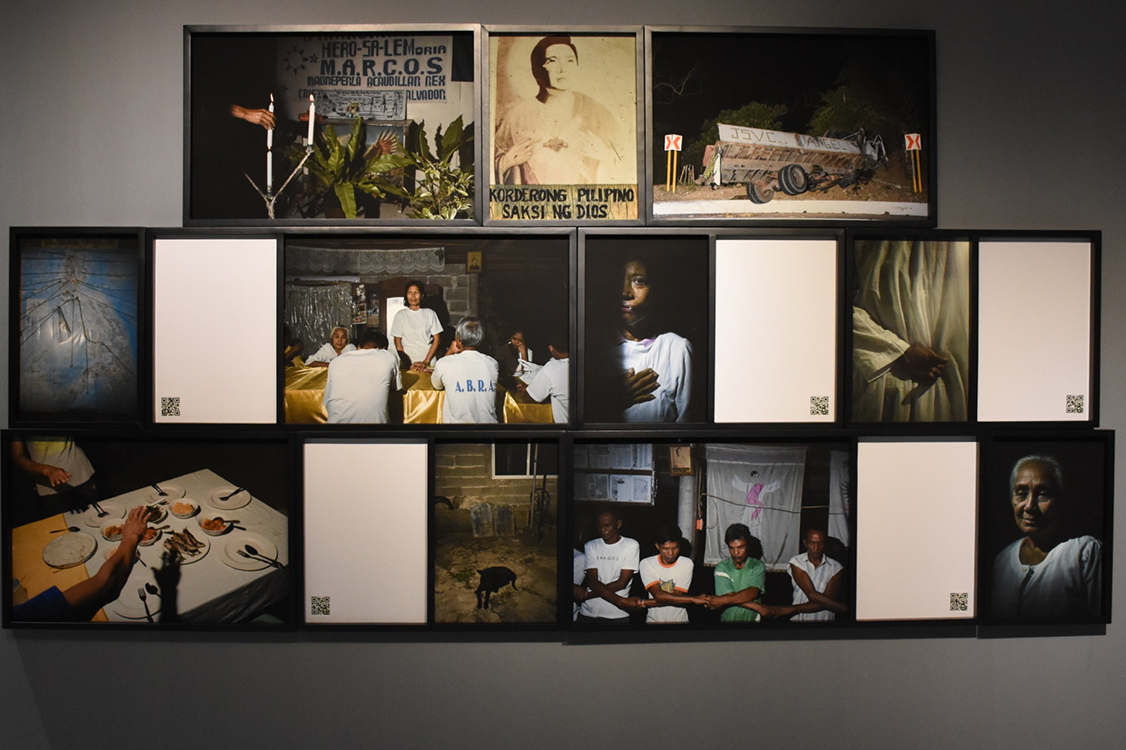

The survey exhibition covers the myriad contributions of 31 photographers based in the Philippines or belonging to the country’s diaspora from the late 20th century to the present. As if trading history for cultural memory, the displays don’t feature in chronological order. The photojournalistic, matter-of-fact documentation of the country’s war-on-drugs by Raffy Lerma and Ezra Acayan, as well as Kiri Dalena’s visual accounts of the families affected by the extra-judicial killings, do far more than roil the stomach. Apparent throughout the exhibit is a visceral kind of closeness, a physicality that bellows tones of immediacy across the gallery walls, even if it has us writhe.

If the seemingly divergent works do not cohere into some continuity, then it must be a kind of gravity that arrests us. To the situation, and with how each individual work pulls viewers in, particularly for those more inconspicuous such as Lawrence Sumulong’s “Dead to Rights” line of Viewmasters and the accompanying barcodes of Carlo Gabuco’s “The Other Side of Town.”

It’s not all overt social engagement, but the alarming number of works contributing to that implies much in line with Shaw’s connecting thread, “[The artists] were in fact, documentarians—of their interest, aesthetic and social concerns, and of the times in which they live… their artworks exemplify the diverse range of photography-based approaches and perspectives exploring cultural and socio-political issues today.”

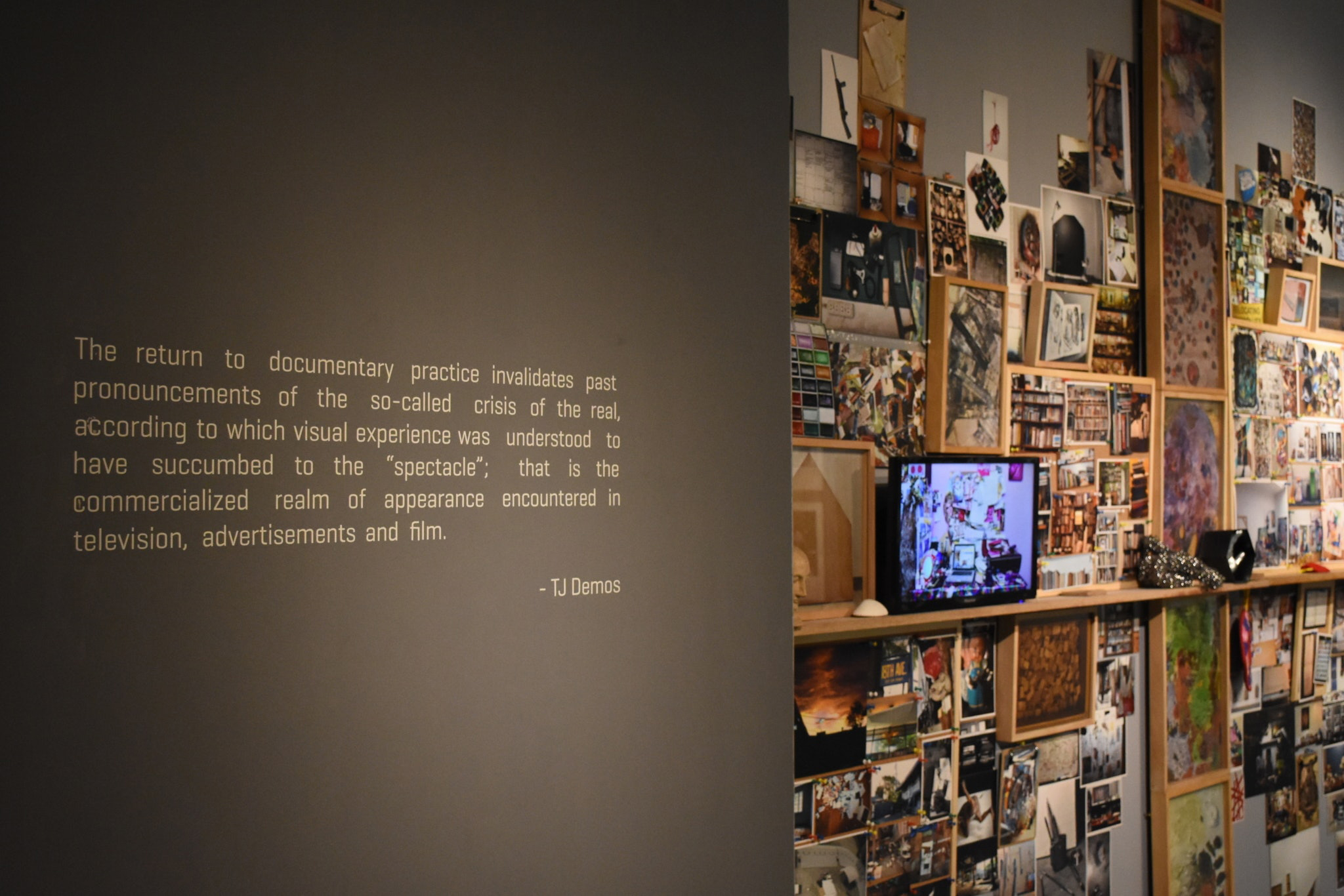

The works assimilate viewers through context, interaction, and the liminal process of meaning-making the show space allows. Exemplified here is MM YU’s “Subject/Object,” a photocollage whose paramount feature is the lack of an explanatory text, possibly a rebuff toward the quick-to-consume. The array of subjects, from the seemingly miniscule to the overblown in scale, are skillfully leveled, inviting viewers to return from what present media platforms may not have been: vessels for contemplation. Mindful engagement shapes the memory, of which Not Visual Noise is a palace.

It’s here that the primacy of the gallery wall does the trick. As viewers amble about and “breathe the totality of each work and its details,” as per Shaw’s request, Shaw also extends the curatorial question in the conclusion of her essay: “What is visual noise?”

Yet, can we even pretend for the works to be noise, still, when it would—at the very least—embarrass us to deny such depicted realities exist? Maybe the challenge doesn’t lie in drawing a line between what is and what isn’t visual noise, but, rather, for how long.

Not Visual Noise runs until March 29, 2020 at the third floor of the Ateneo Art Gallery. The display schedule may be affected by recent news regarding Covid-19.