Corinne de San Jose is a film sound designer noted for an oeuvre of considered, intentional works. While also working on mainstream projects in advertising, her practice in the independent circuit has stayed loyal to an overriding ethos of quality storytelling above all else.

Sound in film is essentially influenced by the space in which a film is shot in. As the adage goes, editing can only build upon what’s already been collected. A sound designer might reduce or increase the volume of certain ambient sounds in a recording, but these stay in the final product one way or another. It was this awareness that likely influenced the output from de San Jose’s artist residency in Calle Wright last year.

The residency culminated in Open House: counteracts, a show shared with three fellow artists, Daniel Chong, Lesley-Anne Cao, and Gary-Ross Pastrana, which opened in November 2025. She shares that Calle Wright’s non-commercial goals enabled her to experience this project as repose from her usual work, “a creative break.”

As such, sound designers are essentially good listeners, working within the space they’ve chosen as their medium. What happens if, rather than an element to a work (as in the case of film), a sound recording becomes the focus?

At first blush, one might interpret de San Jose’s latest sound installation in Calle Wright as such, but experiencing Open House: counteracts leaves a more nuanced impression. As Gary-Ross Pastrana wrote in the exhibition notes, the show creates space for “the practice of listening to grow” where “imprints are not erased but received as a given signal.”

Guests walking through Calle Wright’s rooms may find that de San Jose’s recorded sounds are almost indistinguishable from the ambient sounds emerging from life in this sleepy corner of an otherwise bustling Malate. The only indicator that a sparrow chirp, buzzing tricycle engine, or the pealing laughter of a barkada of students is recorded is the faint static from the transistor radios dotting key corners of the ancestral house-cum-art space.

Calle Wright, an experimental space by Silverlens Galleries, inhabits an old home in Malate, Manila, composed of “twin” buildings with a similar layout in each. It is part of a larger ancestral family compound, marked by two sprawling balete or banyan trees each growing out of the remnants of an old, now-demolished patio.

Utilizing such a floor plan, de San Jose placed transistor radios on corners, along the hallways and rooms, and around the courtyard housing the balete trees. Each radio is tuned to a specific frequency playing ambient recordings produced by the artist during her residency. Broadcasting these recordings are four transmitters placed strategically in sections of the twin houses where the signal is most likely to reach more radios. This is also aided by one of the balete trees being decked—like a Christmas tree—with copper wires and bells, adding sonic layers to the broadcasted recordings.

As guests immerse in the visual component of de San Jose’s recordings and in the installations by the rest of the artists, these “echoes of echoes” play in the background and highlight how the space itself doesn’t just contain the art, but is a medium for the pieces.

It’s interesting to note how the artist chose analog and more dated methods, when more convenient and more commercially-available setups exist: For one, she could have simply hooked up a series of speakers connected by a cable or even Bluetooth to a single device playing the recordings. This choice of installation ties it to the desire to (re)create the importance of pausing to listen amidst an overstimulated digital media landscape.

“Silence is a concept I constantly negotiate with,” de San Jose wrote in December 2025, “I think about the weight and space it creates. I think about its relation to noise, because it can only exist in that duality. As the world around us has become increasingly chaotic, I’ve also grown nostalgic for it. Silence has become this precious, precarious state I willfully have to orchestrate.”

There’s also an element of ephemerality—or ritual—to it as every morning, Calle Wright’s gallery staff needs to tune the radios to the appropriate frequency lest they stray into commercial FM radio stations. In her past non-film projects, de San Jose has also touched on the psychological impacts and philosophical underpinnings of both traditional rituals and the act of ritualizing.

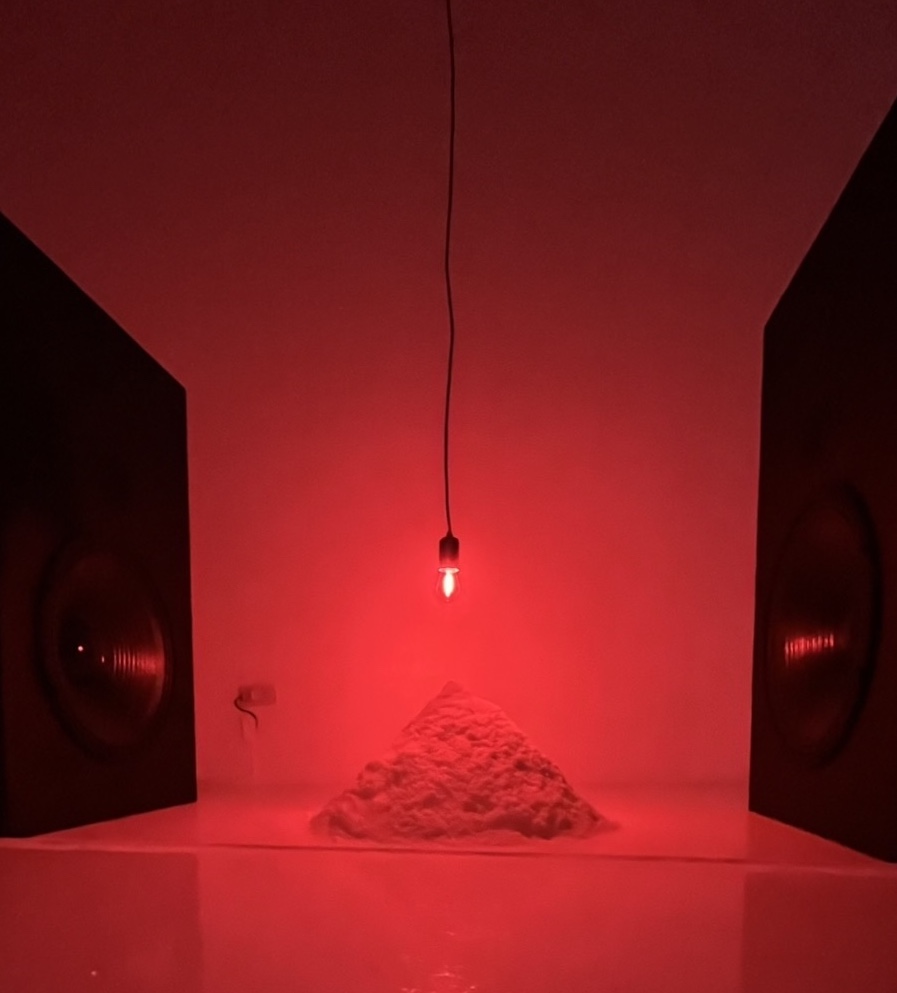

de San Jose has deployed similar works in a parallel group show at Edoweird Gallery where she presents an installation of two big speakers, a mound of salt and a red light fixture. The sound of slow and repetitive movement of waves emitted from the speakers consists of digitally reconstructed audio of different speeches by two authoritarian leaders through the erasure of words that speak of violence, and the symbolic use of salt and red light, the work suggests the “sisyphean cycle of cleansing and contamination” as described in the notes.

In the Calle Wright show, she tuned the transmitters to play at a frequency traditionally believed to hold healing properties. Many traditional healing practices, like those of the Tibetans, Aborigines, and ancient Indians and Chinese utilize music and sound.

Equally important to the show’s implied message is the notion of welcoming, rather than masking, sounds. In fact, it seems that the choice, unconscious or not, to label a sound as a “noise” is also being questioned.

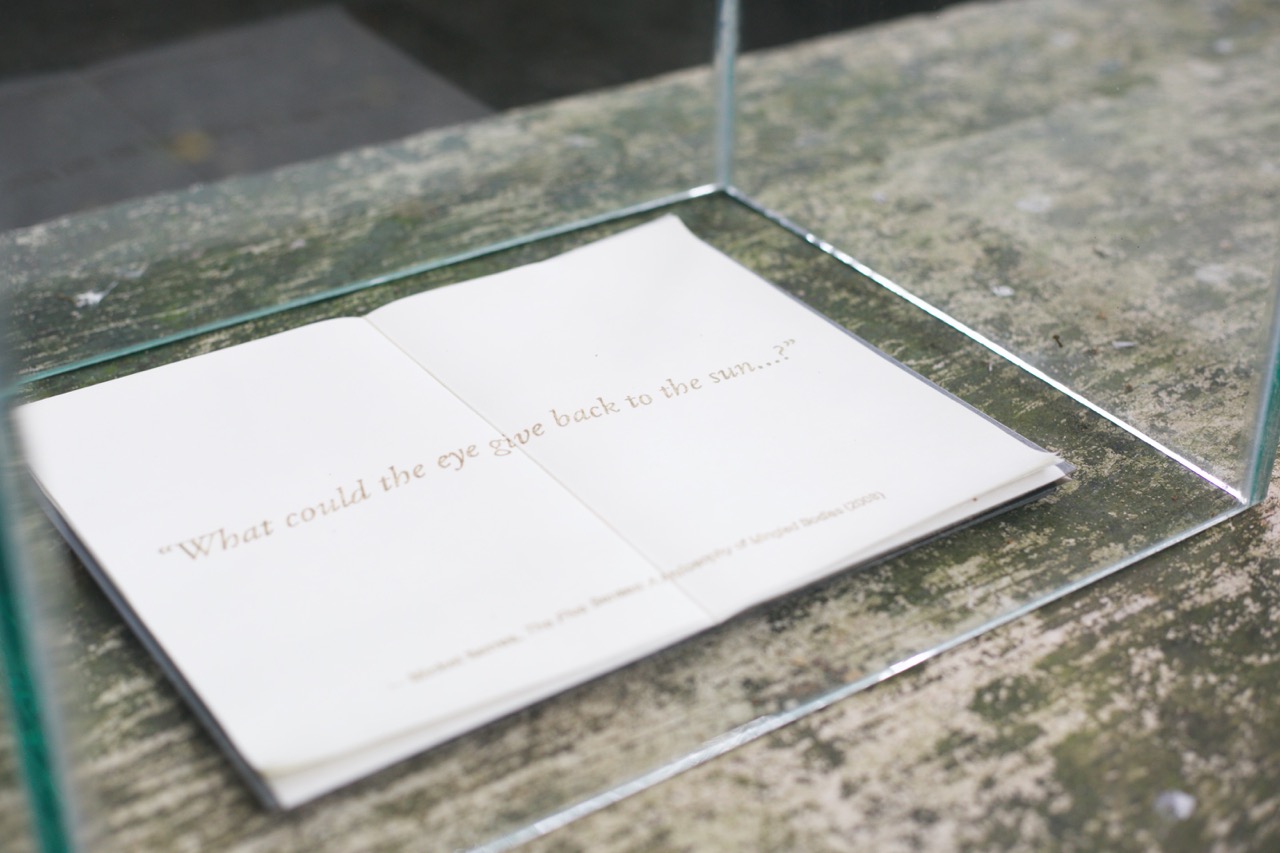

A single work by Gary-Ross Pastrana and Lesley-Anne Cao sits between the two balete trees on a bench in the courtyard. Their collaborative work is a book encased in glass, opened on a two-page spread with one line printed using coffee in a large font which reads “What could the eye give back to the sun?” The act of blending with the surrounding teasingly echoes what de San Jose seems to be doing as her recordings merge with the ambient sound already present not just in Calle Wright, but in the Malate neighborhood.

Meanwhile, visual installation pieces by visiting Singaporean artist Daniel Chong seemingly accompany guests as they walk through Calle Wright. The first set of his works consist of torn underwear taking the shape of cobwebs mounted on the house’s actual CCTVs. These culminated in a bed of bougainvillea leaves made of crepe paper, in which the artist painstakingly folded and twisted each blossom to appear realistic.

Chong’s works in particular create an interesting dialogue when taken in with one’s full attention as de San Jose’s soundscape plays on. Like de San Jose’s works, these are best appreciated when one pauses to allow details in.

The small number of works from each artist placed strategically in commanding corners of each room or space within Calle Wright seems to invite guests to pause—to not simply browse room to room but to immerse not just in the works, but in the space holding them.

Lores and legends abound that Calle Wright is haunted, and this isn’t surprising, given Malate’s storied history, once an artist’s village surviving wars and colonization, now a notorious red-light district.

But the world of Open House: counteracts is first and foremost, open, to the possibility of perceiving noise and silence as imprints. What if ghosts are people too? What if Calle Wright isn’t so much haunted as it is enchanted?

Zen schools often train students through koan, roughly analogous to riddles designed to baffle normal logical thinking. Famous examples include “the sound of one hand clapping” taught by old master Hakuin Ekaku or “show me your face before you were born” from the Gateless Gate compendium. Both are taught as introductory material in dojo around the world, including the Philippines, and trace their lineage to Japan. Koans are often tackled in order, and a single koan may take years to work on. There are hundreds of koans spread across volumes of text.

One such koan simply asks a student: Save a ghost. It seems through the ritual of tuning radios to sounds already-present in the space, Corinne de San Jose plays an ode to the specters of Calle Wright.