In 1986, Antique Governor Evelio Javier was assassinated in the province’s capital, San Jose de Buenavista, an event that remains central to the province’s collective memory. Today, the exact site of his death faces the former provincial capitol, now rebuilt as the National Museum of the Philippines San Jose de Buenavista. Its inaugural exhibition, Paghabül sa Antique opened in July 2025 and is the sixth iteration of Hibla ng Lahing Filipino, recognizing Antique and Panay Island as strongholds of weaving traditions. The Museum stands as a testament to the province’s endurance, binding survival to memory.Yet for whom is it built? To what extent does the exhibition enrich the lived experience of its audience that it necessitates its display in a state museum?

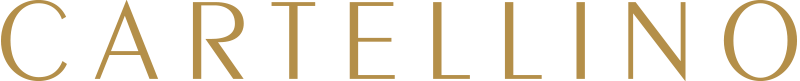

Initially constructed in 1921, the Old Capitol Building was severely damaged during World War II. This led to a series of renovations, the latest of which was completed during the pandemic [1]. I visited the Museum in August with my maternal grandmother and younger relatives. This was the only exhibition on view. Upon entry, I was confronted by a map of Panay Island, showing Antique, Iloilo, Capiz, Guimaras, and Aklan, summarizing the province’s “existing” and “known” weaving traditions, according to the map legend. This first display raised questions: how can an exhibition compress centuries of practice into something digestible? What separates so-called “existing” from “known?” The exhibition attempts to visualize living practice through geography, translating a tactile, intimate process into a cartographic one.

Beyond a place of display, the Museum introduces a new perspective on how art and culture are valued. It joins the National Museum of the Philippines’ efforts to extend its reach beyond the nation’s capital, toward regions once excluded from state representation. Its presence in Antique brings with it three assumptions that shape my understanding of Paghabül sa Antique: first, that there exists a narrative in need of legitimization; second, that the Museum is of value to the community it inhabits; and third, that its location holds national significance.

The Need for Legitimization

By nature, museums legitimize what they exhibit. They decide what is worthy of preservation and attention. Paghabül (“weaving” in Kinaray-a), from the exhibition title, asserts that weaving, often confined to the realm of “craft,” deserves institutional regard. Its being the Museum’s first and only exhibition is already a statement: that textile knowledge, long marginalized, can anchor the province’s cultural narrative.

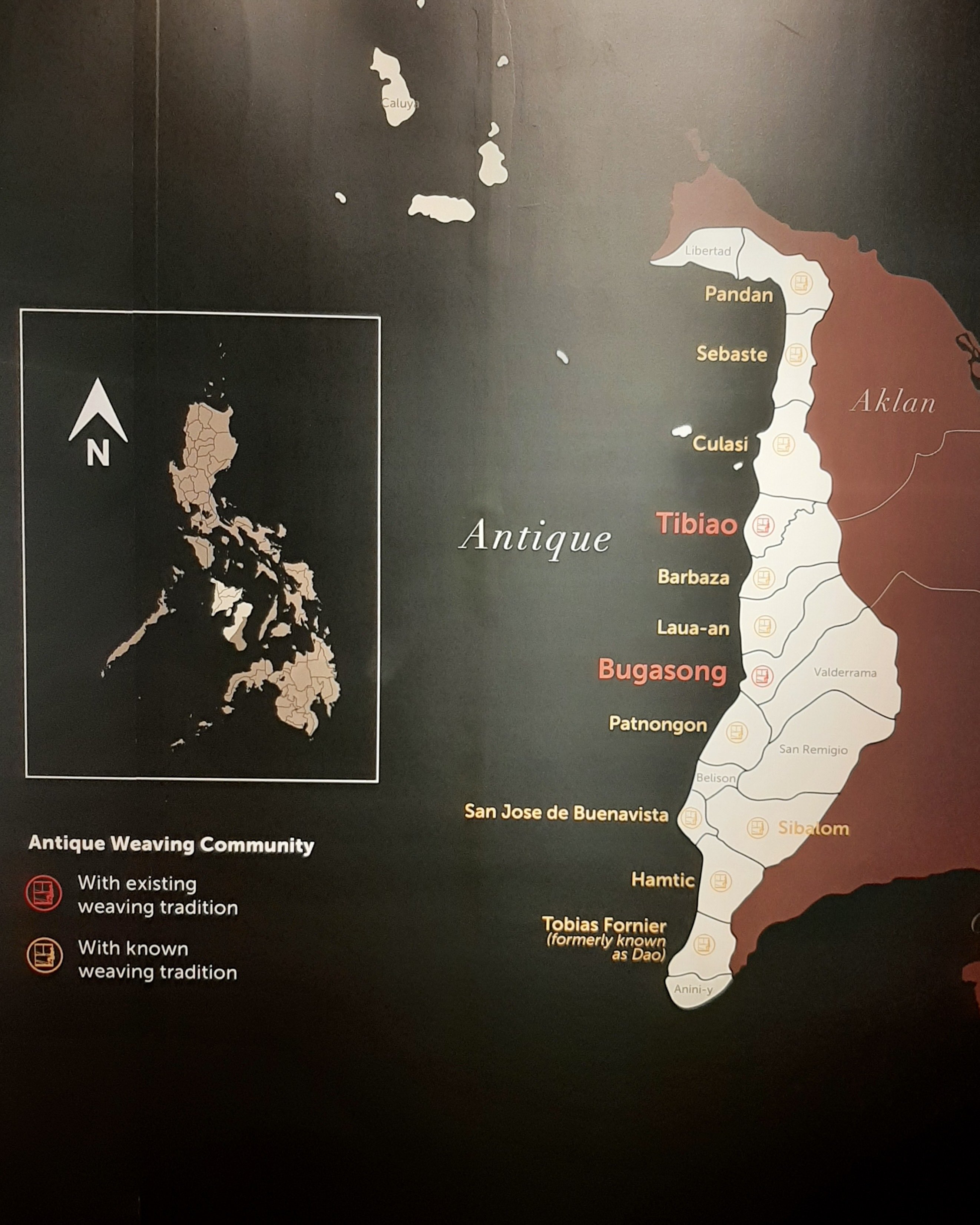

“What comes before textiles?” asked a panel, both in English and Kinaray-a: Anu ayhan ang nauna antes ang tela? In one section, visitors were invited to blindly feel inside boxes of raw fiber and guess which is which. A short description of each fiber, namely abaca, cotton, piña, and silk, detailed what it is often used for, both in the pre-2000s and at present. Though a simple exercise, it highlighted a type of education that weavers are experts in, one that is not as easily taught in a typical classroom.

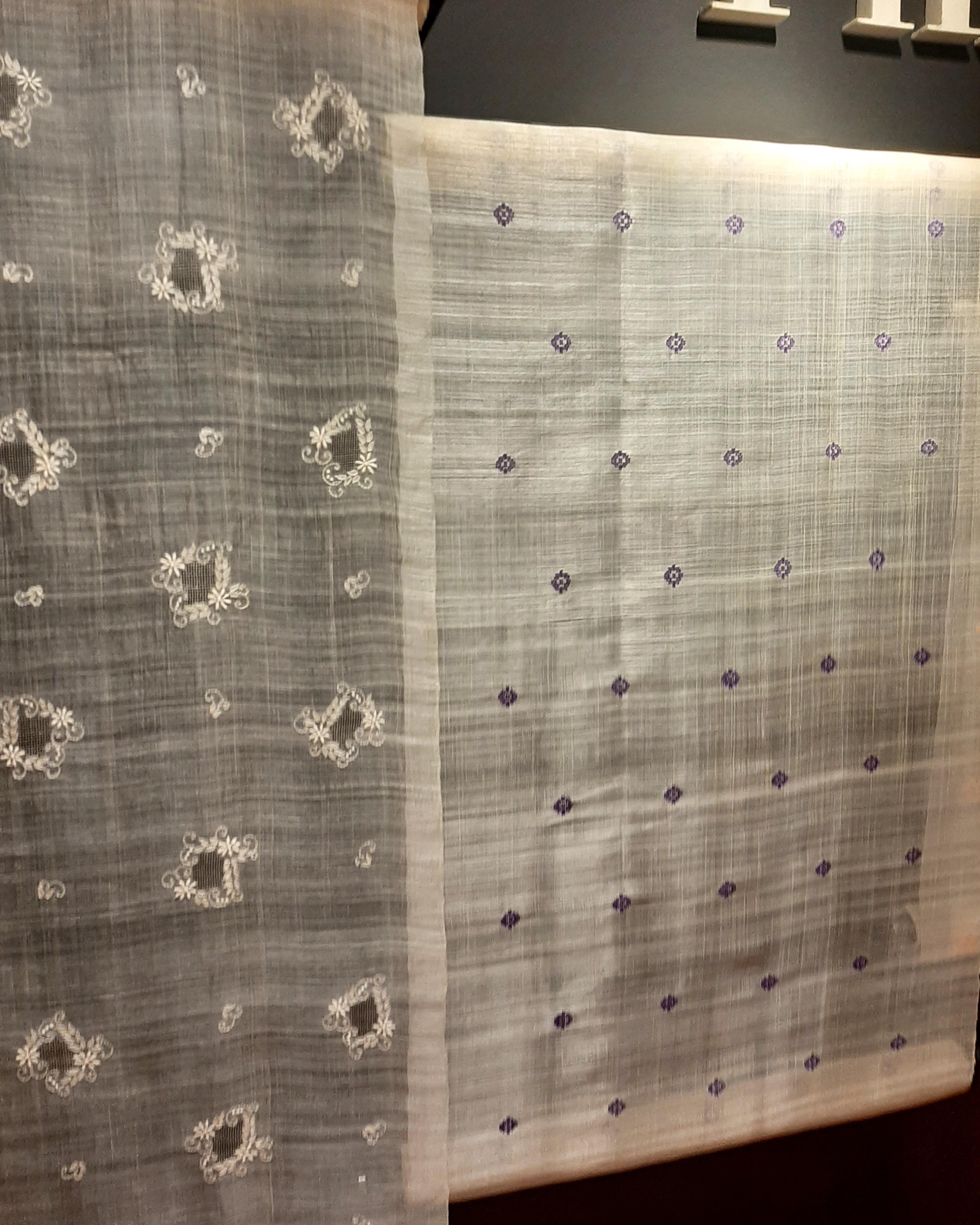

The textiles displayed in the exhibition depict not only an inventive way to create, but, more importantly, a knowledge intertwined with land. The weavers of Antique work with abaca, cotton, piña and silk; their craft is an archive, carrying intelligence passed generation to generation. To display these works within a museum is to acknowledge their intellectual and cultural depth, yet it foregrounds a risk of confining them within the frame of the “artifact.”

Art theorist Cecilia de la Paz discusses the dangers of exoticizing provincial communities in The Appropriation of Local Culture in Museum Practices, calling museums to redefine their role beyond collection and display [2]. A museum that treats its cultural artifacts and objects as traces of a faraway culture untouched by modernity fails its community, sanitizing their narratives to conjure idyllic images instead of the complex histories at play, one that has adapted through colonialization, government changes, and technological advancements.

These are not remnants of a lost world; they are living expressions still practiced, refined, and adapted. How then does institutional framing influence our perception of weaving as both historical and ongoing?

Authorship complicates contexts further. Unlike fine art, whose makers are often singular and named, textiles are communal works. In an art world that privileges the lone genius, this recognition of collective authorship offers a quiet resistance. When community work enters the museum, it meets another system of value, one governed by historical policy and institutional frameworks. The encounter is uneasy but productive, opening questions of how cultural knowledge is mediated when placed within institutional walls.

The Museum’s press release notes that while Antique’s weaving was once dominated by women, men now engage in tasks such as harvesting and transporting fibers. The gendered reconfiguration reflects a living system, responsive to contemporary realities rather than static tradition. The Museum’s responsibility, then, is not only to exhibit this knowledge but to sustain its dialogue with the communities that keep it alive. This leads us to the second assumption: that the Museum is of value to the community it is built in.

The Museum and the Community

The National Museum of the Philippines, as it now stands, began operations in 1998, though its origin traces back to Spanish colonization. Its main home is in the capital of the Philippines, Metro Manila, where the complex resides in three categorized buildings: Natural History, Anthropology, and Fine Arts.

Since 2016, admission has been free, part of a broader initiative to expand access. More recently, the institution has opened branches in Cebu, Davao, Iloilo, Dumaguete, and, in 2025, Antique, classified as “regional, area, and site museums” [3]. Unfortunately, the National Museum of San Jose de Buenavista is not visible on their webpage, which may render this inaccurate.

Behind the establishment of the Museum was Hibla ng Lahing Filipino, an ongoing project by Loren Legarda tracing Philippine textiles, beginning in 2013 at the National Museum of the Philippines in Manila. As a project, it has travelled in its different iterations through other regions in the country like Ilocos Sur and Iloilo as well as foreign cities including Berlin, Washington, and Lisbon, among others [4]. Considering Hibla as the system in which Paghabül sa Antique lives, this essay acknowledges this programming but remains rooted in the latter exhibition as it stood in San Jose de Buenavista.

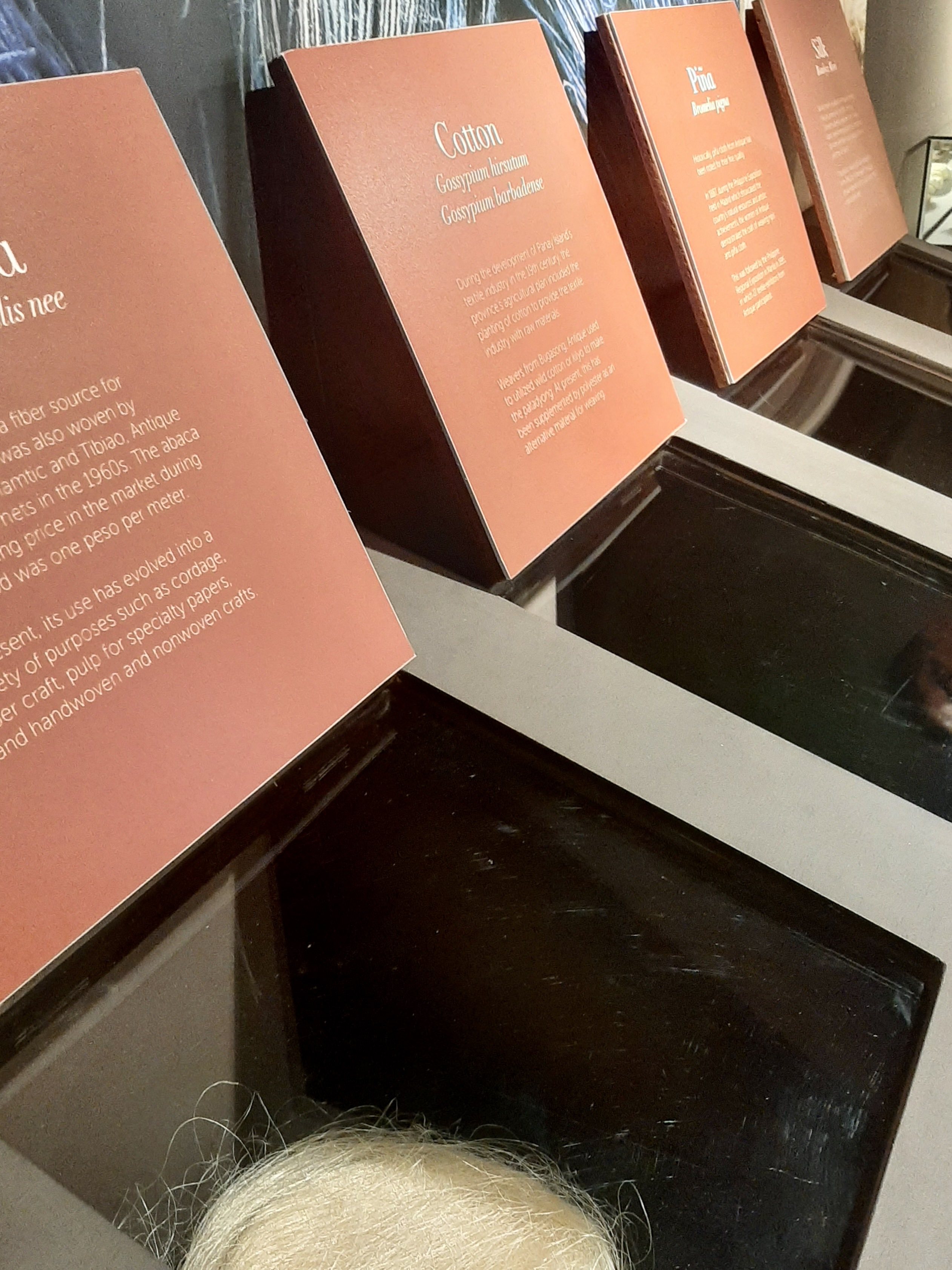

By establishing a museum in Antique, the state assumes its presence benefits the local community. Certainly, its educational value is evident: a group of students were at the gallery during my visit. I imagine that they are better off tracing patterns of panubok with their own eyes and inspecting the threads of piña seda, as the current exhibition allows them, than simply seeing images of the textiles on a screen. For them, the Museum provides tangible access to cultural heritage.

In theory, the Museum functions as a resource for researchers and cultural workers, a site where the study of weaving can continue. Whether it will fulfill such a promise remains to be seen. Its location, across the site of Javier’s assassination, presents a powerful continuity: both are spaces of remembrance. Here, memory is not monumental but woven, refusing elegy and asserting persistence through making.

Still, the question lingers: for whom is this value defined? Upon leaving, my grandmother said softly, “Nami ba.” A literal translation, “It’s so good,” fails to capture her tone: part wonder, part disbelief, more akin to, “It’s amazing, isn’t it?” Her quiet amazement was itself a measure of the museum’s power, to make the familiar seem new.

The Significance of Place

To situate a National Museum in Antique before other provinces is symbolically charged. Expansion beyond Metro Manila signifies inclusion, marking certain sites as nationally significant. The Museum’s very presence declares that Antique embodies something essential to the Filipino narrative.

Paghabül sa Antique positions weaving as both heritage and cultural emblem, but this framing carries a curatorial challenge: to hold weaving as a living practice while historicizing it. The exhibition design attempts to address this duality: a video loop shows the weavers’ labor. Women pick grass, soak them in dye, set up the loom, thread the string, and so on. Text panels in Kinaray-a and English detail stories of indigenous culture, primarily of youths in these communities. Both formal education and lessons by culture masters become vessels for the younger indigenous people. Curiously, the text extends beyond weaving masters, listing Sugidanon (epic-chanting, of which the region’s Manlilikha sa Bayan Federico Caballero was recognized by the state in 2000), Ambahan (welcome joust), Dilot (love songs), Taida (musical repartee), Duruyanon (lullaby), Hinu-anon (traditional stories), Ulaw ofhay (long narratives), and Binanog (courtship dance). This asserts the deep research and community engagement that preceded this gallery, foregrounding a respect for the indigenous peoples’ lived experiences.

Simultaneously, gestures toward “contemporaneity” occasionally falter. Mannequins on rotating platforms risk turning the weaves into spectacle. In a corner, a weaved duyan (hammock) invites visitors to sit and swing, though a warning sign against hitting the wall feels oddly misplaced: was it an afterthought or a playful nod to museum decorum? My grandmother enjoyed it as a photo spot. In her home in Belison, she has a similar duyan, yet this one, staged under museum light, had been transformed into artifact.

To claim Antique’s place in the national consciousness, the Museum must navigate the line between reverence and recontextualization, between tradition and accessibility. Significance, after all, is not discovered but declared. The province becomes visible when framed by the institution’s gaze.

Reflections on Place, Audience, and Self

“Creating a museum is only the beginning of a process involved in housing the nation’s heritage,” writes curator Ana Maria Labrador in UNESCO’s 2010 report on community-based approaches to museum development in Asia [5]. Paghabül sa Antique begins that process in a place already marked by memory. Across the site of Javier’s assassination, the Museum undertakes another act of remembrance, one that looks not to loss but to continuity, to the quiet persistence of its weaving communities.

To write about Paghabül sa Antique critically is not to diminish its achievement, but to place it within the larger dialogue of representation and regional agency. It is to insist on its complexity: how the language of the museum meets the language of weaving. The friction between them is productive, revealing how institutions translate lived knowledge into heritage and how communities negotiate that translation in turn.

I stand both inside and outside this history. I did not grow up in Antique, yet I recognize its patterns. My grandmother’s quiet “Nami ba” captures this friction better than any exhibition text. It is an expression of astonishment that her own world, once ordinary, could be made extraordinary under museum light.

That is the Museum’s most urgent task: to sustain that astonishment, not by displaying objects, but by keeping it open, active, and in conversation with the people whose hands continue to weave.

References:

[1] “Tourism | San Jose de Buenavista.” The Municipality of San Jose de Buenavista’s Website, sanjoseantique.gov.ph/tourism-2/. Accessed 16 Oct. 2025.

[2] de la Paz, Cecilia S. “The Appropriation of Local Culture in Museum Practices: Problems and Possibilities for Philippine Communities.” Suri Sining: The Art Studies Anthology, edited by Reuben Ramas Cañete, Art Studies Foundation, Inc., 2011, pp. 152–168. Scribd, https://www.scribd.com/document/846327646/De-la-Paz-C-The-Appropriation-of-Local-Culture-in-Museums. Accessed 14 Oct. 2025.

[3] National Museum of the Philippines. “Regional, Area and Site Museums.” National Museum of the Philippines, www.nationalmuseum.gov.ph/our-museums/regional-area-and-site-museums/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2025.

[4] Torrevillas, Domini M. “Loren Legarda’s Hibla and Baybayin.” Philstar.com, 28 Oct. 2013, www.philstar.com/opinion/2013/10/29/1250634/loren-legardas-hibla-and-baybayin. Accessed 20 Oct. 2025.

[5] Labrador, Ana Maria Theresa P. “An Ethnography of Community Museum Development and Museum Studies in the Philippines.” Community-Based Approach to Museum Development in Asia and the Pacific for Culture and Sustainable Development, UNESCO, 2010. UNESCO Digital Library, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000189902. Accessed 5 Oct. 2025.

Further Reading:

Adamson, Glenn. Thinking through Craft. Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Labrador, Ana Maria Theresa P. 2016. Hibla ng Lahing Filipino: The Artistry of Philippine Textiles. Exhibition catalog. 2nd edition. National Museum and the Office of Senator Loren Legarda, Manila.