It was easy to miss To Find Gold in a World That Needs Silver, an exhibition by artist Jose Olarte at Gravity Art Space Gallery held last July 11 to August 6, 2025. The show was mounted in a tiny cubicle, about the size of a passenger elevator, and located inside one of Gravity Art Space’s back galleries. One could mistake it for an employee’s storeroom unless you looked inside.

The tight and claustrophobic feel of the space contributed to the atmosphere of the exhibition. The floor was covered in fake grass. The ceiling was divided into a grid of backlit tiles. Two tiles depicted different skies: one showed a clear, sunny day with tree branches gently swaying in the breeze; while another tile depicted ominous storm clouds along with the noise of thunder and incoming rain. A third tile depicted a ripple traveling across a computer-generated grid. Most jarring was the dolphin that stuck out of the ceiling, as if it was about to dive into the room. It carried a Penguin edition of The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in its mouth, which hinted towards the exhibition’s commentary on capitalism, labor issues, and social inequality. There was clearly a glitch in the matrix.

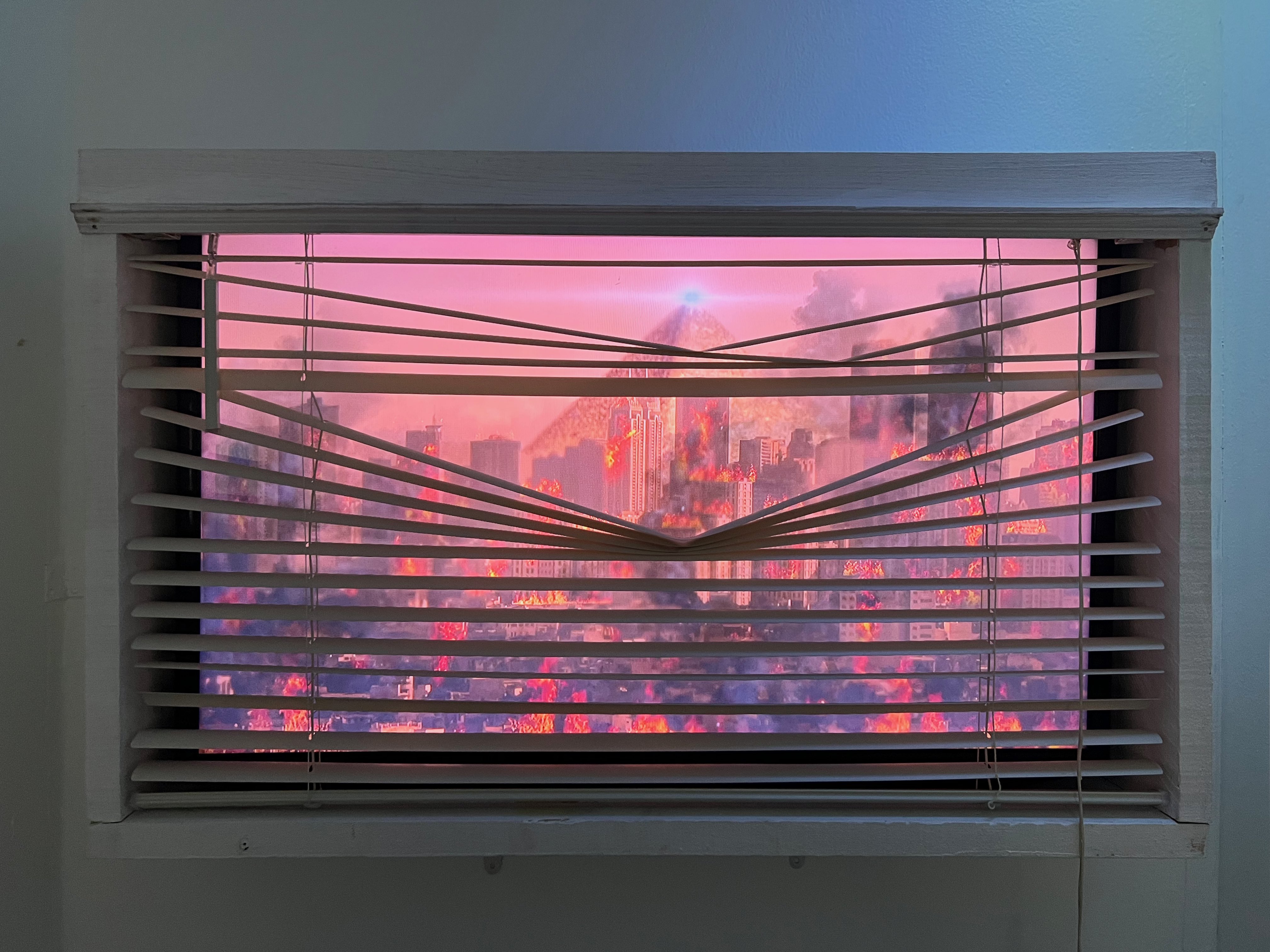

On the wall was a video showing a city on fire with a glowing pyramid in the background. It was mounted in a white box that made it look like the viewer was peering through the broken blinds of a high-rise window. On the opposite wall was a photograph depicting a forest or overgrown garden. Dark storm clouds and bolts of lightning loomed above. At the foreground of the image was a fence with bright plastic flowers and cans repurposed into plant pots. A hand-written sign reading Cash For Work was attached to the top of the fence.

It was a strange, unsettling experience. The tight space made the exhibition feel more immersive, as you were trapped inside and couldn’t distance yourself from the installations. It felt like you were watching the city burn through a window, helpless to stop it. Meanwhile, a dolphin hovered in mid-air, as if falling from the sky. It evoked the sensation of a surreal, alien apocalypse.

Jose Olarte is a filmmaker, photographer, and curator whose works touch on social issues. In 2025, he joined the group show What Power Leaves No Room for Autonomy? at Kalawakan Spacetime, a presentation for the inaugural edition of the Quezon City Biennial. The artists in the show represented the empire by incorporating its scraps: maps, scrap metal and fabrics, bureaucratic diagrams and videos. Through this, they insisted that “‘aid’ from the empire isn’t charity, but something that is done, and it’s ‘time for the capitalist powers to pay up.’”

Meanwhile, Olarte’s solo exhibition Gyre Dominion, held at Mono8 Gallery in 2024, was based on his research on the Angat and Caliraya Dams. The mixed media exhibition took place in a dark, concrete room, which gave it a gritty feel. CRT TVs stacked together displayed diagrams drawn over videos of lush green mountainsides, representing the nature destroyed by construction and industry. Collages consisted of mechanical parts of a hydroelectric dam: gears, fans, and a synchronizing panel featuring the Woodward logo—a real American company that manufactures aircraft engines and hydro turbines. The exhibition explored the positive and negative effects of hydroelectric dams. While they provide electricity to the public, they also destroy the environment, displace farmers and indigenous people from their lands, and underpay workers. However, in true Olarte fashion, he added some humor to the bleak subject matter. A mirror with the words Main Character Energy written around its border hovered over two videos of the Philippine President’s and Vice President’s eyeballs staring blankly at each other.

To Find Gold in a World that Needs Silver felt like a natural progression of Olarte’s work and themes. He continued to tackle socioeconomic inequality, but this time, he injected much more humor and fresher ideas. While he included more explicit examples of critical theory, his approach was open-ended and absurdist enough that it encouraged viewers to research further and think about whether they or not they agreed, rather than wholeheartedly advocating for a single cause.

The exhibition text explained the artist’s vision.

“This is Fine.

In an era where hard work doesn’t necessarily produce rewards, and where work anxiety is all but normalized, what does it really mean to be working class in the 21st century?”

The dolphin with a copy of The Communist Manifesto was a reference towards Posadism. While Communism is a political theory that advocates for common ownership and the abolishment of social class, Posadism is a later branch of Communism that the Argentine activist J. Posadas developed in the 1960s. Internet memes about Posadism often include images of dolphins, as Posadas believed that humans should communicate with these animals.

Posadas was also notorious for his belief and support of extraterrestrial life. He argued that UFOs could only become technologically advanced enough to travel to other planets if they had evolved past selfish capitalism and developed a communist society that focused more on cooperation and technological development over profits. Posadas then advocated for humans to cooperate with aliens, as he believed that aliens could help humanity suppress poverty.

The 1960s saw both technological advancement and human suffering. The Soviets and the Americans sent the first humans to outer space and the moon. The Cold War carried the threat of humanity’s extinction through nuclear weapons and mutually assured destruction. In Southeast Asia, the Vietnam War raged on, aided by the US military. In Posadas’s Argentina, various coup d’etats had occurred.

It’s not difficult to see the parallels between the 1960s and 2025. Today, war rages on in Ukraine and Palestine. Barely five years ago, the world was overcome by a pandemic. And now, AI threatens the jobs of employees around the world. Furthermore, we are bombarded by climate change: melting glaciers, rising temperatures, and storms and floods that worsen with each year.

Perhaps humanity seemed so hopeless that Posadas could only seek salvation from outer space. Jose Olarte’s view of the world was equally bleak. The city burns, the storms rage on, and yet ordinary people still have to work. The desperation to have a job, to make a living, is so extreme that one will state Cash For Work instead of the opposite. Owning a property full of plants and trees isn’t enough to feed or support someone in this world; you still need a job.

As chaos unfolds, only the elite living at the top of the pyramid remain safe and unharmed. It would almost be a blessing to have an alien dolphin fall from the sky and offer humanity the gift of salvation in its mouth. But we don’t need aliens to restructure human society. By citing human thinkers like Marx and Posadas, Olarte hints that humans can also solve our own problems. Humanity has dug its own grave, but we can work together to get out of our own hole too.

Gold is a valuable status symbol, but silver has more practical uses. Silver represents the working class that supports the bottom of the pyramid. Gold represents the elite at the top. In Olarte’s video, the top of the pyramid glowed with a steady, calming blue light. It towered over the rest of the city skyline, its inhabitants safely protected from the fires and smoke of the streets below. We, the viewers, could only helplessly watch the destruction from the window of our dwelling. Our vantage point was somewhere in the middle; not at street level, but nowhere near as high as the tip of the pyramid. Furthermore, it was a tiny exhibition space, similar to the “coffin home” condominium units in Hong Kong. We aren’t millionaires; we are average people.

By approaching such serious subject matter through the absurdity of communist dolphins and a meme in the exhibition text, Olarte lightened the mood of his exhibition. The absurdity could make one laugh, but more importantly, it showed the importance of optimism and a sense of humor in such a bleak world. One ceiling tile showed a stormy sky, but another one showed a clear, sunny day with green leaves fluttering in the wind. The garden with a sign that read Cash For Work was decorated with colorful, handmade flowers repurposed from plastic trash. The dolphin referenced Posadas’s belief that humans should also communicate with dolphins. Posadism’s entire vision of communist aliens saving humanity is absurdist and humorous, but ultimately, it advocates for cooperation over pure self-interest. Yes, the world is on fire and we cope with memes of dolphins and dogs drinking coffee. This is fine. It will be. Perhaps, if we’ve got each other’s backs.

All images courtesy of Gravity Art Space.

Frankie Locsin is a writer and cultural worker based in Metro Manila. In 2022, she was shortlisted for the Ateneo Art Awards - Purita Kalaw-Ledesma Prizes in Art Criticism.