Perhaps the defining moment in the conversation between Filipino artists Judy Freya Sibayan and Eric Zamuco one August afternoon at Silverlens Manila was when the word “derivative” entered the room. In IP parlance, derivative is what you get when you translate, adapt, abridge, arrange, or alter a literary or artistic work1—an exclusive right exercised by the original author, lest infringement follow.2

But this was not a clinic on copyright. And no one’s suing anyone. Sibayan was less interested in statutory precision than in the baggage the word has accumulated in the art world. In certain circles—particularly those orbiting modern and contemporary art’s more promiscuous forms like assemblage, readymades, and installation—derivative can be a polite slur. It can imply laziness or ineptitude, the nervous suspicion that an artist has merely gathered the leftovers of others’ artistic labor. The anxiety is not unfounded: in a milieu already drowning in material excess, the audience will not tolerate a mediocre assemblage. Because the prima facie artfulness of the work lies in the materials themselves, the assemblage artist is always under trial—every slight change in construction measured against the charge of unoriginality.

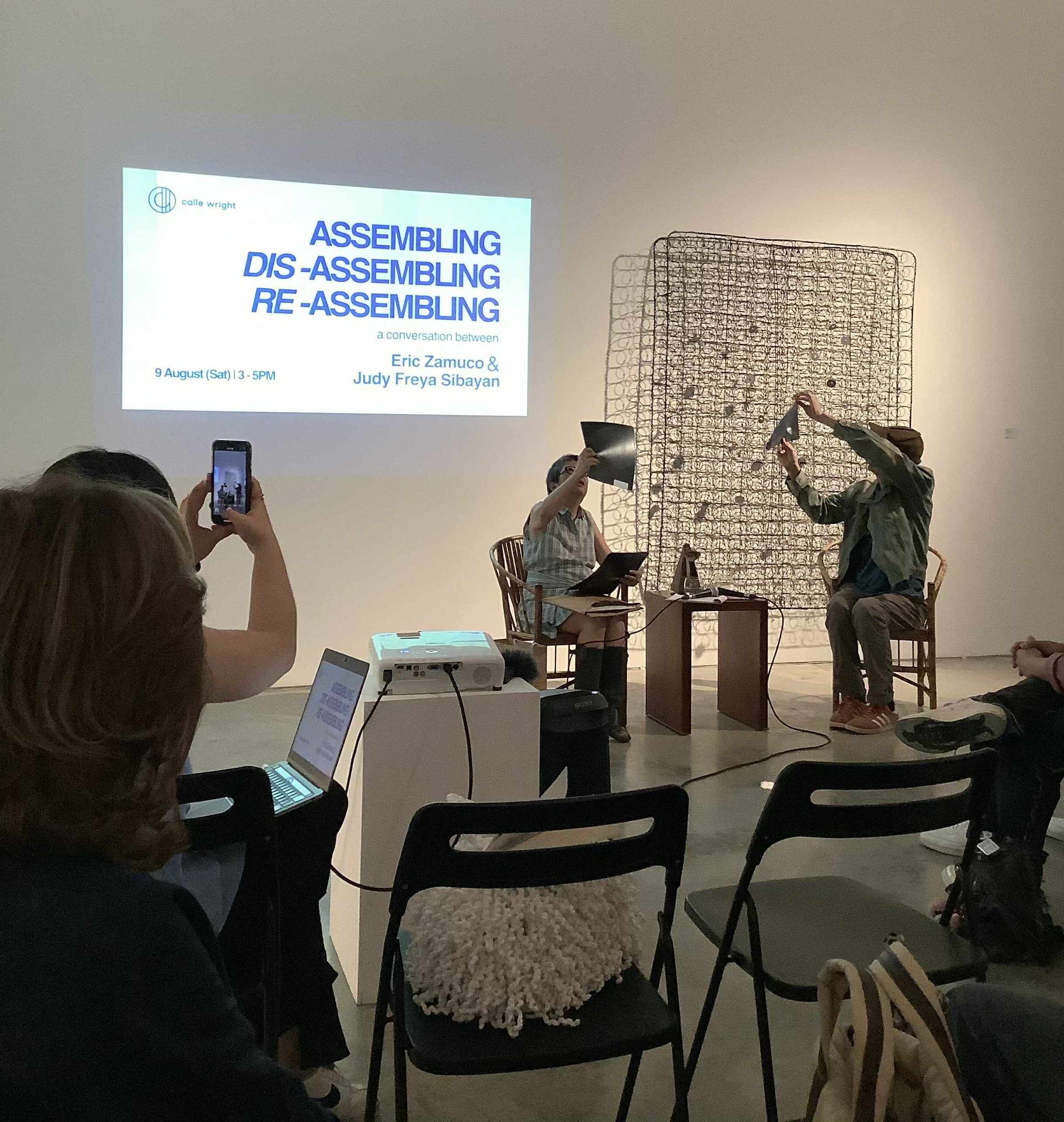

The two artists sat across from each other on the occasion of Assembling, Dis-assembling, Re-assembling, a closing dialogue marking the final week of Zamuco’s seventh solo exhibition Sa Ilang (In the Wilderness). The show gestured toward the “junk” ethos of neo-Dada, in which assemblage was a key strategy, but without the anarchic aesthetics of the street or the studio—these works sat neatly, and even elegantly, within the white walls of the Makati gallery. They offered, too, a vantage point on Zamuco’s evolving practice, one defined by fluctuating densities of material—wood, metal, plastic, textile—yet anchored in the sediment of deeply personal archives. After completing his MFA in Sculpture at the University of Missouri, he lived for several years in Massachusetts before returning to Manila in 2012, a cycle of departures and returns that would become more than biographical detail: it informs the very grammar of his work. Sibayan, whose own remarkable self-archive exhibition is on view at Calle Wright, played both provocateur and guide, teasing out the historical matrix of Zamuco’s approach while situating it in the broader tensions of contemporary art.

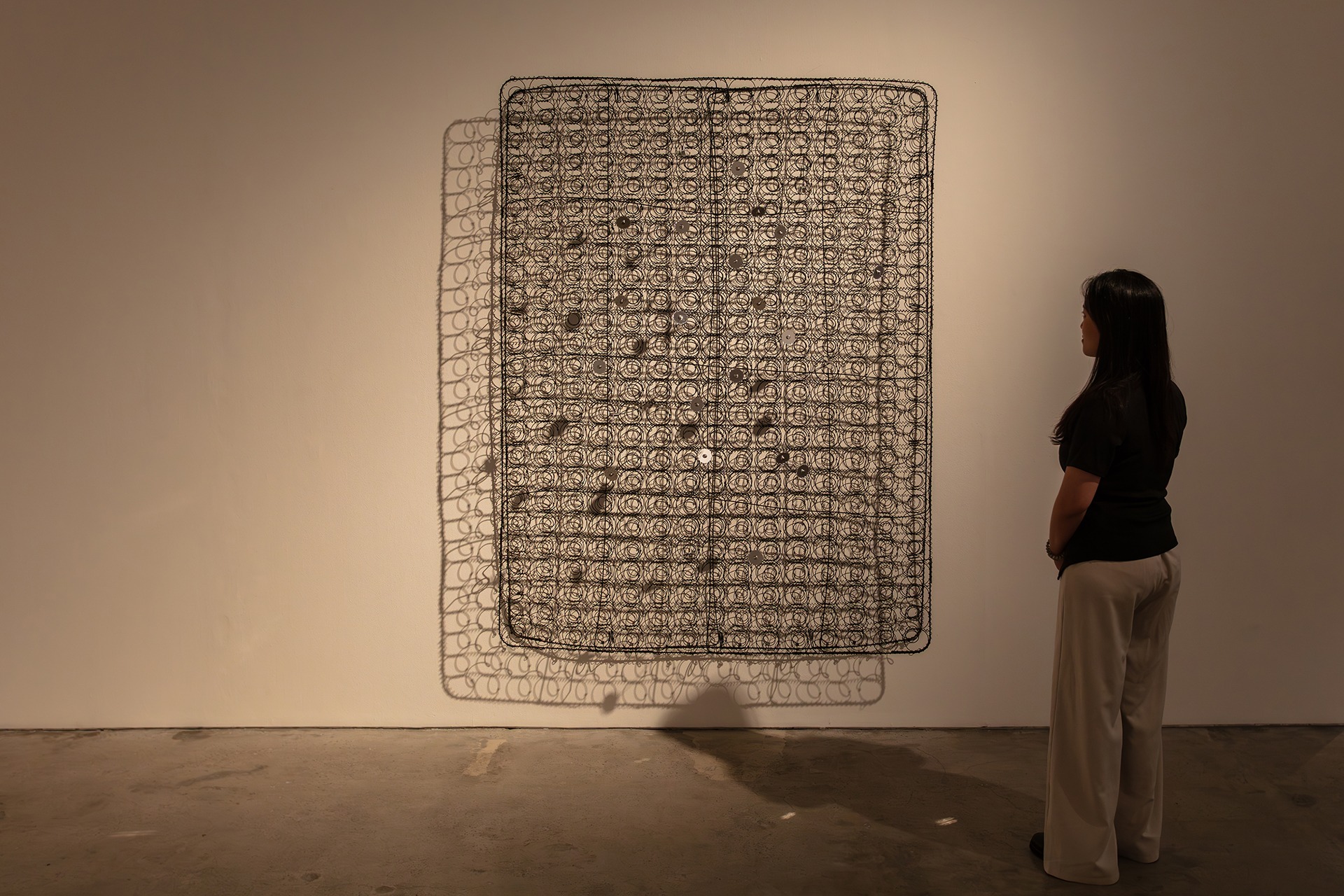

From a bird’s-eye view, Zamuco’s wilderness is a thermoplastic terrain. Its undergrowth is a canopy of acrylic sheets, which curator Josephine V. Roque assigns it as the “syntax” of his works. In Salud (2025), for instance, acrylic serves as the canvas for UV prints of pictures and postcards sent by Zamuco’s grandfather to his grandmother while seeking work in Zamboanga. The structure is scaffolded by singed wood and stainless steel fasteners. In Akatan (2025), perhaps the most understated piece in the collection, laser cut acrylic mirrors bloom as wildflowers. It is almost impossible to believe that this bed spring—once an ancillary object of domestic and intimate life, the hidden armature of nightly rest—now appears as a coiled skeleton, reconstituted into austere geometry, delicate yet enduring.

Upon closer look, one cannot ignore the complicated—often violent—history of the material. Before acrylic became a fixture of consumer design, it was a wartime essential, prized for being lightweight yet shatter-resistant, an ideal medium for airplane canopies, gun turrets, and submarine periscopes. In the interwar period, plastic carried utopian promises of stability and abundance, so much so that historian Jeffrey Meikle heralded it as a democratizing material to banish scarcity.3 That optimism has since yellowed; acrylic now speaks as much to fragility and environmental consequence as to resilience.

What we do not often realize is that acrylic itself is a derivative—born from methacrylic acid through the alchemy of industrial chemistry. Long before it arrives in the artist’s hands, it is already freighted with past lives, already conditioned by functional design. For Zamuco, those biographies intersect with his own. His assemblages fold together inherited objects, scavenged matter, and fragments of family memory—an ongoing negotiation with the residues of migration, loss, and return. Polymer becomes more than a medium. Transparent, it filters; reflective, it mirrors. Always, it withholds as much as it gives. Zamuco works with acrylic as if in full command of what chemists call its “morphological adaptability.”

To this, Sibayan cautioned against overreach: “The basic idea of assemblage is the artist’s very little intervention in the individual material.” So what, then, remains of the creator’s job? “The assembling is the work,” she clarified.

The assembling is the work. The entire conversation flirted with this volatile construct of originality: while the legal world has long reduced it to two building blocks—independent creation plus a modicum of creativity—the sacrosanct duty in this discipline lies elsewhere. It is not to refine the nature of the objects but to (re)organize them, to coax them into new configurations, whether toward harmony or deliberate disarray. This is no secret to those who have followed the practice: Norberto Roldan honors this duty through his reliquaries of the everyday; Mideo Cruz, with his irreverent fusions of icon and debris, does too.

And though the assemblage artist—Zamuco included—may borrow from his predecessor, the collage maker, or acknowledge his godfather, the sculptor, or even slip into the skin of his more cosmopolitan cousin, the installation artist, he is always reminded that in his work nothing is ever final. This impermanence is not a deficiency but a method: to gather, to fasten, to loosen, to start again.

“It is easier to disassemble than assemble,” Zamuco admitted after a long pause.

“It’s like going home.”