“You’re a printmaker now!” Angela Silva anoints me as I hold my breath and methodically peel the paper off a gelatin plate at a printmaking demo in Valencia, Negros Oriental. “We need men!” she quips.

Much like in the Miriam Toews novel and the subsequent Sarah Polley film adaptation that inspired this article’s title (Women Talking, if not obvious), the women at Mugna Gallery can be both blunt and subtle at once. Silva underscores the fact of the matter: the virtual impossibility of talking about Philippine printmaking, both as a practice and a process, without acknowledging the women printmakers who bore witness to its legitimation as an art form. As critic Leonidas Benesa wrote some five decades ago, women “constituted, as it were, the collective matrix in which the art of printmaking was partly to gestate and develop into [a] full-grown organism.”1

In Negros, the exhibition Echoing Messages serves as a result of this history. It is a congregation of ten women artists whose individual practices are largely facilitated by the printmaking medium, spanning relief and reduction printmaking, serigraphy, monoprint, gel plate printing, and beyond. The show runs until February 23, 2025 at Mugna Gallery.

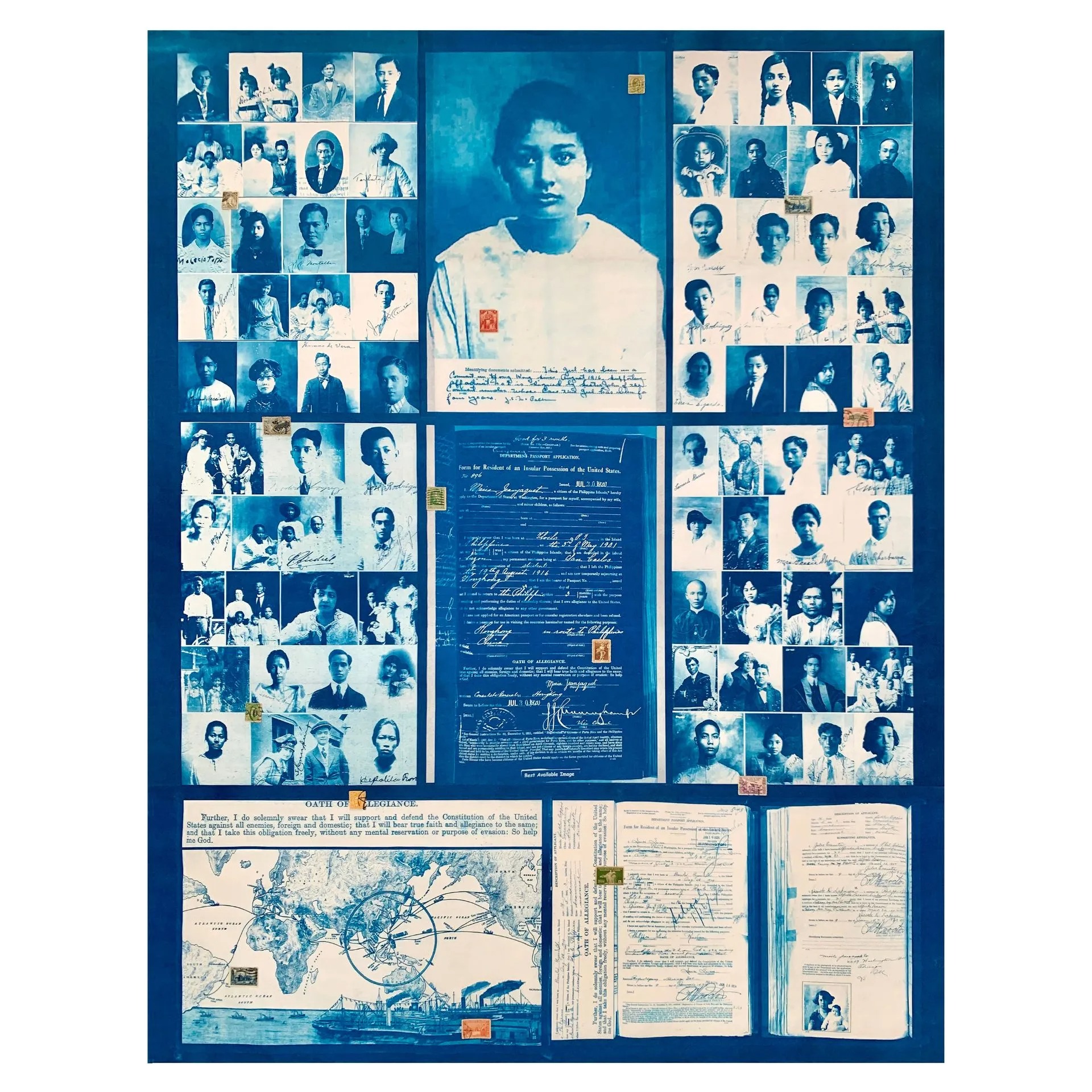

Silva, who has mounted solo cyanotype projects at Qube Gallery in Cebu and the Negros Museum in Bacolod for the past years, returns with a little over four feet grid of her monochromatic blue prints. Collectively titled I Will Bear True Faith and Allegiance, the images were derived from travel documents and identification photos of Filipinos during the American colonial period.

A migrant artist herself, Silva’s movements between the United States and the Philippines enable her to articulate regulated bodies in the context of travel and mass movement. Picture after picture, the printmaker intervenes in this visual archive, reappropriating mere administrative records as spectral portraits of diaspora.

At the print demo, Silva shares the worktable with Kristen Cain, who primarily employs found objects as tools in her printmaking practice. Cain is also no stranger to crossing geographical borders, having moved from the U.S. to the Philippines where she’s exhibited collagraphs, culled out from a process that fixes everyday items into a matrix to create ornate, multi-layered prints.

In one way, their respective journeys as trasnational artists mirror what they inventively call the landing / take off inking technique: the printmaker strives to fluidly glide the inked brayer onto the plate, roll it up, and without a hitch, lift it off to create a seamless spread of ink. Repeat until the application is even and no corners are missed. The simplicity is deceptive; the method demands some muscle memory and precision, evident in the printmakers’ exacting yet delicate work.

From separate tables, Irma Lacorte and Tin Palattao—the artist duo behind ILCP Art Space—and printmaker Gabi Nazareno, introduce me to their stock-in-trade: handheld rollers, ink bottles, old newspapers, and some more sheets of paper.

“There’s a lot of wastage in printmaking,” Lacorte admits as she pulls an initial print from a tabletop wooden press and makes a second pass with the ink left on the plate. The result is a ghost print: necessarily a faded copy from the ink residue, often discarded but capable enough to surprise Lacorte with its shifting tones and textures.

Nazareno agrees with Lacorte. The Cebu-based artist has just finished rubbing the back of a paper placed over her wooden block with what looks like a synthetic spoon, thoroughly applying pressure in a process called burnishing. Doing away with a mechanical press, burnishing makes possible, albeit laboriously, the uniform transfer of ink onto the paper.

Added to her arsenal is laser-cut technology as is used in her exhibition piece The Twins. Here, she deconstructs a rubbercut print on wood into geometric pieces and assembles them again in protruding layers like a jigsaw puzzle. The resulting image is augmented to near abstraction.

Indeed, Echoing Messages comes with a bag of tricks and techniques: Fara Manuel’s two-block color print Baguio Daydream on acid paper and Marge Chavez’s Dead Dove: Do Not Eat, Pt.1, a consequence of the chine colle method which is used to adhere a lightweight, often colored or textured paper to a sturdier backing paper. Screenprinting enters the fold with Maya Muñoz and her phantasmal renderings of people and landscapes, reminiscent of her 2023 solo exhibition Drift and Vapor at Silverlens Manila.

Regardless of the method, printmaking, as much as it makes visible the ridges not readily seen, also works in the language of subtlety. To the untrained eye, Nazareno’s woodgrain impressions may seem like flaws that need correcting; Lacorte’s ghost prints might be mistaken for unwanted remnants. Yet, these artists recognize that while taxing standards are demanded of this craft, there is always room for the spontaneous to break in.

Printmaking’s reputation precedes itself. This has prompted critic Dr. Patrick Flores to ask: “How does the work of print harness the potential of a medium that is by nature reproducible and multiple?”2

Marz Aglipay’s Marzing Machine engages with this problematique. Essentially devised as a gachapon-style vending machine, it dispenses pocket-sized prints hand-pulled by the exhibition-goer who is consequently positioned as an active participant in a commercial exchange. Beyond modes of interactivity, the printmaking process is made to form part and parcel of a supply chain; it takes a back seat as a preparatory step to the transactional procedure of consumption.

For Aglipay, the installation—it has been toured in group exhibitions and is certainly a crowd-puller—is an integral component of her inquiry into consumer culture, one that is not only driven by the capitalistic trade of commodities but is also informed by how an article, as simple as a farmer’s market produce, reaches domestic spaces of home and family. This theme finds resonance in Hershey Malinis’ stack of rubbercut prints on reused corrugated boards, each bearing images of sardine brands.

Outside the art world, print has historically occupied contentious economic and political territories. It has entangled with the excessive worlds imagined in corporate advertising, the (false) promises made in election propaganda, and in more recent public debates, the kind of images we choose to enshrine on our new polymer banknotes. Whether it’s the face of a historical figure or a natural wonder, money—as printed matter—does more than represent purchasing power; it serves as a canvas on which we attempt to refine our sense of nationhood and collective identity.

Back in the gallery, making a case for printmaking as art has already dispensed with the staunch defense of the medium. By now, and especially now for emerging artists, it has become a reprieve from the ever-confounding, tyrannic world of the digital. For the more tenured ones, it simply has withstood the test of time.

Echoing Messages, in terms of scale, is a modest showcase to the sweeping surveys its predecessors have done elsewhere, as in the 138-artist lineup of Tirada 50 Years of Philippine Printmaking 1968-2018 at the Cultural Center of the Philippines in 2018 or the three-gallery exhibition Proven and Printed: ILOMOCA Print Festival at the Iloilo Museum of Contemporary Art in 2023.

But this does not deter the expansive imagination of the women who, despite the limited real estate of galleries from the regions, affirm that the printmaker-as-artist discourse has long been archived in the dockets. No longer is there a need to litigate the place of printmaking in Philippine art history—thanks to the makers who saw past the limits of the medium and put in the necessary work.

Notes

[1] Leonidas Benesa, What is Philippine about Philippine Art? and Other Essays (National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 2000), 59.

[2] Patrick Flores, “The Strike of Print,” in Tirada 50 Years of Philippine Printmaking 1968-2018 (Cultural Center of the Philippines, 2020), 10.

Echoing Messages: A Print Exhibition was on view until February 23, 2025 at Mugna Gallery, Valencia, Negros Oriental.

Denzel Yorong is an independent media producer and writer.