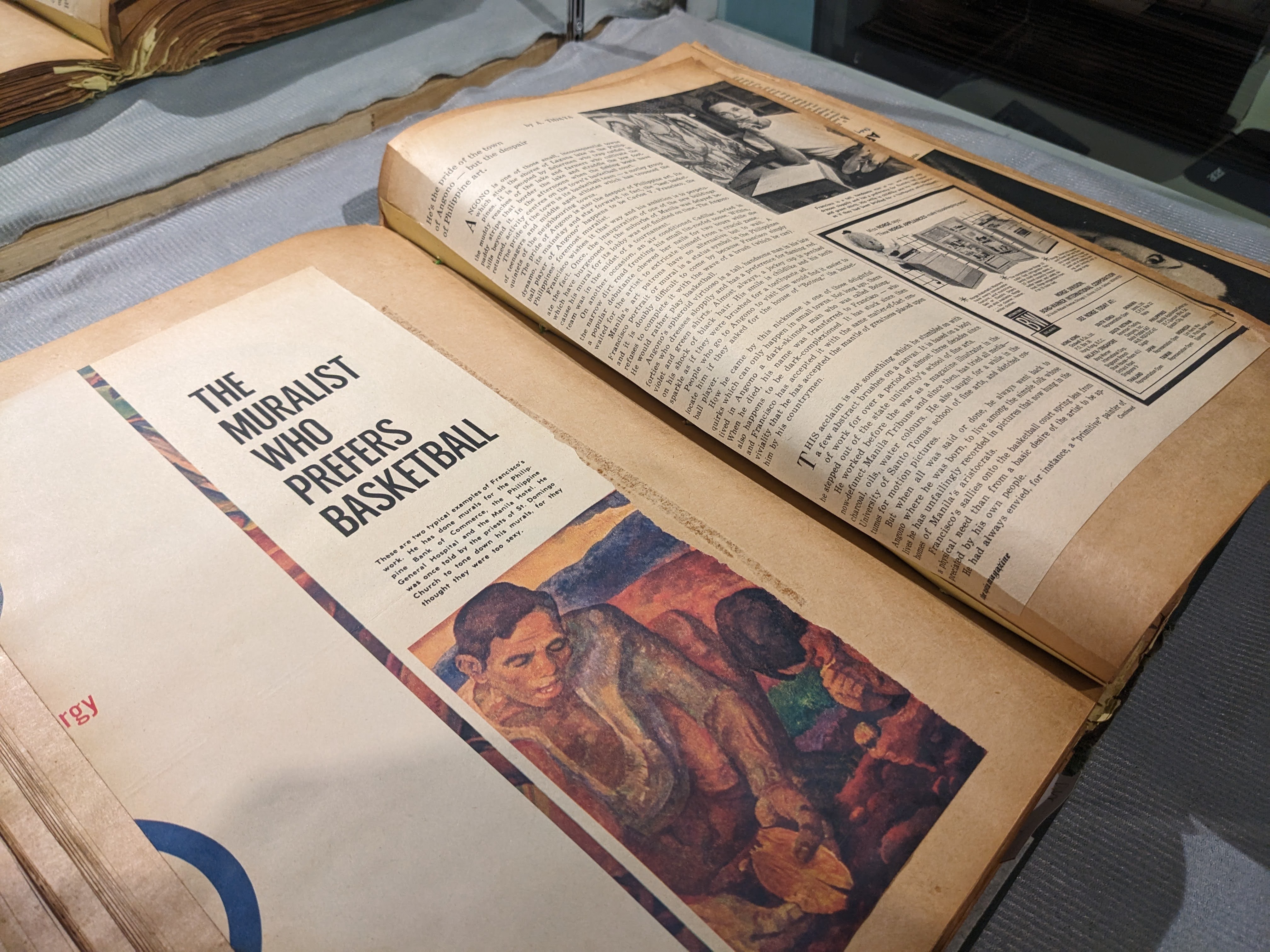

Note: This essay was first circulated as part of the exhibition, The Muralist Who Prefers Basketball, by Sofia Santiago-Jimenez. With the essay incorporated as an exhibition object—among the artworks—of the show rather than its wall notes or review, its position suggests different functions of written text in exhibitionary contexts. The Muralist Who Prefers Basketball is supported by the KLFI Venue Grant and probes connections between Philippine art and basketball culture. It is on view until January 21, 2025 at the PKL Center, Makati City.

Author's Disclaimer: The characters and events in this essay are fictitious. Any resemblance to persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

1. Magpapasa ba ang mga bwakaw?

"Hindi kasi kayo nagba-basketball, kaya wala kayong pagkakataon makipagbalyahan sa akin”, the old veteran artist started.

It was our last day in an art camp, and we were asked to meet the head mentor at his house. We had a number of scuffles with management during our stay and we were expecting to straighten things out before we left.

The old man laid down his first point and implied that many social barriers could be broken down by a game of hoops. It made sense, and I nodded—playing sports is a great way to get to know a person’s demeanor. We lost this opportunity to connect with him because we never played.

But slowly, as the old veteran, who prided himself for being ‘marumi maglaro’, continued to preach about how tough he was for risking to pursue an art career in the 90s (and grumbled at how kids these days have it so easy), it dawned on me… that we were never invited to play.

Now, bear with me. This piece is more than just a whining of a kid counted out of playtime.

I understand that basketball is not a co-ed sport. But during this art camp, save for one explicitly straight man, no one else in the group of eight artist residents—four male and four female—were offered a chance to join. So it was not about our assigned sex at birth. Our guess was that their game required a specific and outward manliness. The rest that lay outside this standard were carelessly dismissed by the veteran: “Ibang balls kasi nilalaro niyan,” he said, giggling at his own dirty joke.

The Philippine art scene, just like this 5 p.m. recreational basketball game, is a game for the man’s man. This has been pointed out and proven by so many other authors before me. What makes this comparison to basketball especially frustrating is that the art scene is not bound by technical rules. And yet women and the LGBTQ community remain mostly relegated to the sidelines as muses, cheerleaders, and comic relief.

If we did join, will we ruin the seriousness of their game? Was there an assumption that we were not competent players? Do they think we are too fragile?

I have tallied many different lists such as art school year books and catalogs of world fairs, and data shows the same glaring difference between the number of male and female participants in the art scene. But for this discussion, let me show you a quick study of the list of winners of national art contests.1

Last year, looking at the list of semifinalists in Metrobank Art and Design Excellence Competition, only 7 out of the 80 names, or 8.75% are traditionally female. This is a slip down from their previous numbers which were 13% in 2022 and 11.25% in 2021.

We see the same situation in Philippine Art Awards. PAA acknowledged this problem in 2018 by endorsing on their website and social media pages a magazine article titled: The Woman Question. The author Katrina Stuart-Santiago pointed out this discrepancy by spotlighting the only six women artists among the 140 winners in PAA’s 24-year existence. After this, we saw a significant improvement in the following years in 2020 and 2023, with 20% and 15% female names in their list of regional winners.

GSIS National Art Competition has an average of 15% female names among the finalists in the last three years. And while I find it odd that GSIS still separates categories for representational and non-representational painting, this choice reveals interesting data: The roster of finalists in the non-representational category has notably more female names. Last year, 32% or 8 out of 25 finalists in this category were female names, and in the last three years, the list included an average of 26% female names.

What is in this segregation of non-representational images that allows more women to thrive? Is it the special layer of anonymity granted by abstract painting? A variation in tastes during judging? The freedom from the belabored themes of the figurative tradition?

Not everyone sees the existence of competitions as healthy for an art scene: Art shouldn’t be a competition, some would argue; art’s value is arbitrary and any hierarchy is meaningless. But whether or not one agrees, to win a competition is one of the best catalysts for one’s art career. Like the Palarong Pambansa, they become recruitment machines for opportunities to enter the art scene’s “big leagues.” Aside from that, it drives artists to train regularly, much like athletes, to sharpen ideas and master techniques.

Many aspiring artists look at these competitions as beacons of good taste. I remember anticipating the annual delivery of PLDT telephone directories to our home. It felt like Christmas, unwrapping each book and revealing the new winning artworks of their competition, printed proudly on their front page covers. For the rest of the year, I would find myself trying out their techniques and making my own versions of their themes.

Competitions hold so much potential to push artists to meet the responsibilities of art to society: open it to new movements, mediums, techniques, and creative experimentation; generate new levels of dialogues; even forward new perceptions of the self and reality. The relevance of narratives, however, depends significantly on the diversity of its sources.

If left uninspected and held tightly by a select few for too long, competitions can cultivate formulaic derivatives. Like an AI image generator left without new data, it will feed on itself and eventually churn out a homogenous paste. Thus, we too, struggle to outgrow a perception of the self that is flooded by elements of grit and grime, of flesh entangled in suggestions of Philippine flags and obvious tokens, utterly entrenched in the cyclical argument of national identities and by default, its accompanying pain.

We do not blame the select few for being in their position. But sometimes, the best thing to do for the betterment of the game is to look around, pass the ball, and let others play.

2. Balyahan!

We were never able to resolve the clash between the art camp management and the artists. A few months after the conversation with the veteran, things escalated. After several more failed attempts at communication, we did what artists do, and joined other batches to mount an exhibit that processed our collective experience and frustrations into artworks. The veteran did not like this.

Now, rumor has it that I, along with around 20 emerging artists from the camp, have been blacklisted in the veteran’s network of high-profile galleries. I have tried looking at the incident from many angles, even at the possibility that I did deserve the consequence. But from all angles, the blacklist did not seem like a well-meaning criticism. It felt more like an ‘I’ll-injure-you-so-you’d-stop-playing-this-game’ move. News of the blacklist traveled fast, and we became a cautionary tale to warn others not to touch the veterans.

In an ideal world, the incident could have been a chance for a creative jostle about the state of art education in the Philippines. Had there been enough trust between the vets and the rookies, the conversation could have been productive no matter how contestatory it would become. But foul plays like blacklisting, and threats of such, have made this ideal unattainable. While most of us know the need and merit of honest criticism, we cannot all afford the consequences of speaking up against the powerful few.

From where I stand, even the landscape of art criticism in the Philippines seems quieter, very far from what we had in the 70s. On a recent dive into the archives I found published commentaries that easily describe an artwork as: “a clear example of what happens when an artist tries to ‘Filipinize’ a foreign style.” In the same paragraph, seemingly without blinking, the author writes the words “disappointingly” and “least impressive”.2

When was the last time we saw candid remarks like these in print? For quite a while now, we have been coddled by favorable feature articles where the voice of the art writer is often obscured by the intention to promote. The benevolent brutality of art reviews is replaced by rumor mongering, mythmaking, and blacklists.

Criticism now mostly lives secluded in inner circles of collectors and the academe, enveloped in the scope of curators, sometimes hidden out of sight in the judging process of more attentive art competitions. The common folk encounters it in the corners of the internet—in group chats, cryptic social media posts, and anonymous Patreon accounts. Barely documented, and either too close to, or never reaching its rightful beneficiary.

3. For the love of the game

“Brutal ang art scene,” was a mantra repeated during the art camp lectures. “Brutal ang art scene,” they repeated the phrase like a self-fulfilling prophecy.

When I decided to pursue an art career four years ago, I jumped in fully aware that this is not a fair game. Art history has prepared me for this.

“Well, you need money.” The veteran advised us near the end of his last lecture. “There wouldn’t be a Michelangelo if not for the Medicis. Even if their image is unsavory, your art will outlive those circumstances. Good art will always outlive their context," he declared, and my idealistic self winced at recognizing the patches of truth in his words.

Visual art, like basketball and many other things, will always be entangled with money and ethics. These are the forces that write the invisible rulebook. Whichever has more influence in the Philippine Art Scene, I will have to see in the years to come.

In the process, in case we find the big leagues too macho, too important; in case we become weary of its stagnancy and predictability, then we can leave Michelangelo to the Medicis.

The rest of us can always play our own game at the grassroots, where it’s easier to hear criticism, and change the rules when needed; where it’s easier to go back to the essence of artmaking: of connecting with people and basking in unadulterated fun of creating.

Notes

1 ±3 counts for margin of error to account for gender neutral names. The data I have is limited to lists and occasional photos. I acknowledge the need for more thorough research to accurately identify different gender identities in this tally. I hope another researcher can do this in the future.

2 Rocamora, N. F. (1974). Lost marbles. Retrieved November 29, 2023, from https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/roberto-chabet-archive-clippings-and-other-documents/object/lost-marbles.

All images taken by Lk Rigor, courtesy of the Kalaw Ledesma Foundation Inc.