For visual artist Celine Lee, surfaces reveal more than just flat expanse. In her third solo exhibition, A Surface, she etched aluminum prints of Philippine topography onto abaca paper and then pounded the resulting image onto rice paper. The exhibited work is the outcome of casting the two papers together, yielding a strange combination of fragility and depth. “The exhibition is an attempt at pointing out the awareness of space, or lack thereof,” Lee said of the work. “I used abaca and rice paper to establish territorial markers for the Philippines and China, respectively.”

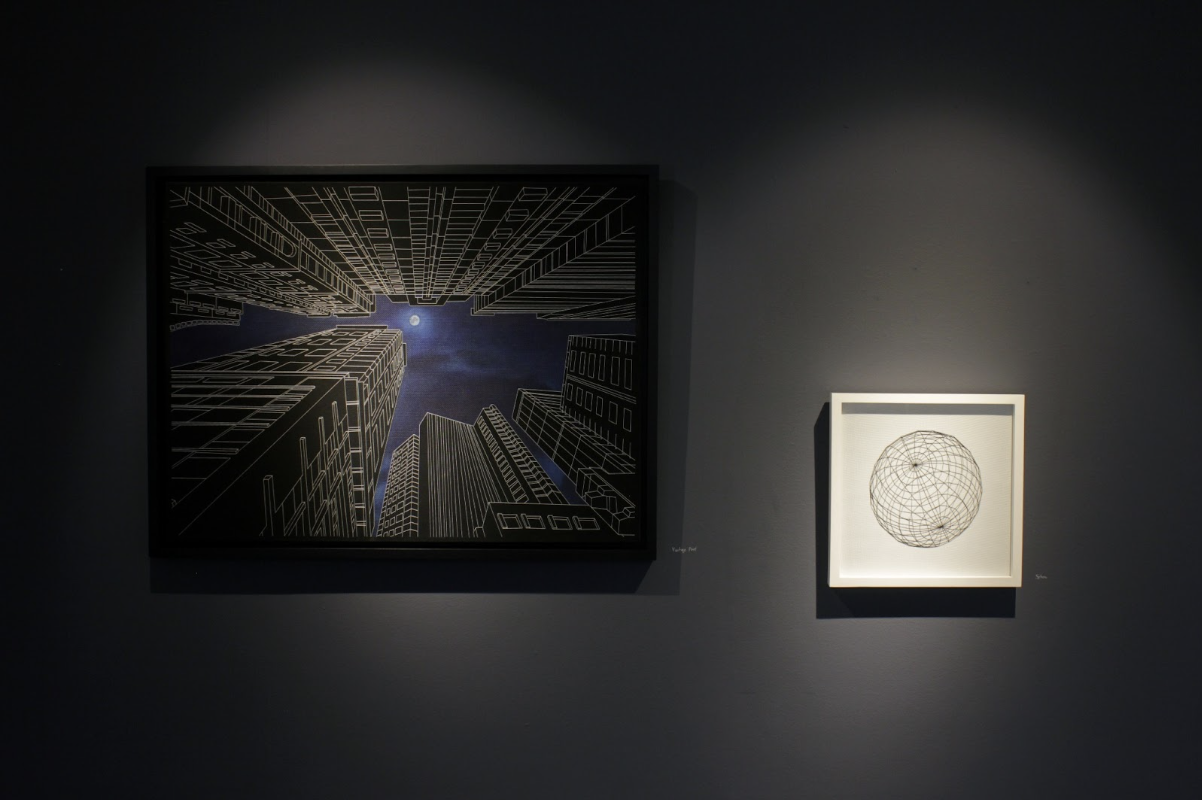

Tinged with geopolitical critique, A Surface feels cut from the same cloth as Lee’s other works: geometrically perceptive experiments that toy with the borders of concept, space, and material. Seeing Lee’s work up close, you get the sense of her attempt to dissolve those boundaries. The artist’s 2020 solo exhibition, The Length and Breadth of Depth, deployed 3D printing to present shadowy portraits, made available exclusively online. Meanwhile, the empty canvases of the supposed paintings are left lingering in the exhibition site, a blank slate of a dwelling.

For her, traversing the relations between the arts and sciences has been a key factor in expanding her art practice. “I think basic math and science can be found in art and vice-versa,” she says, citing “the light spectrum and color theory, geometry and composition, how shadows work, how certain metals oxidize and age over time, chemistry in film photography.” Lee’s preoccupation with the dynamics of science and mathematics bleeds into her view of life in general: “To me, there’s just something inherently poetic about such principles that I can’t help but relate in life and translate in my art. I feel like these things are often overlooked and I just attempt to re-interpret them in my art practice.”

In Lee’s works, the task of rediscovering figments and remnants of the overlooked and the obscure is impelled by a curiosity grounded by a zen-like sensibility. The Brightest Part, her 2022 solo exhibition at MO_Space, saw an arrangement of mirrors across a space—some hanging from the ceiling, others fixed at the center—creating images from the resulting shadows. A soft nostalgia floats through these images, as though seeing a shadow of a leaf casts the object in a sepia-toned, impermanent past tense. The Brightest Part was an invitation to experience, and also to disturb, a simulacra of light.

“The Brightest Part was a pandemic show,” Lee recalls. “I was inspired by the notion of spaces during that time—digital spaces and physical spaces. I was fascinated by the alchemical process of photography being able to capture moments and transporting it elsewhere and wanted to translate that into the show by way of deconstructing it.”

Last year, it was announced that the show was shortlisted in the visual arts category of the 2023 Ateneo Art Awards (Lee’s second nomination). “I was so happy that it got nominated and got into the shortlist. I felt proud of myself because it was honestly one of the most challenging shows I’ve done to date. Logistically, financially, emotionally, it was taxing.”

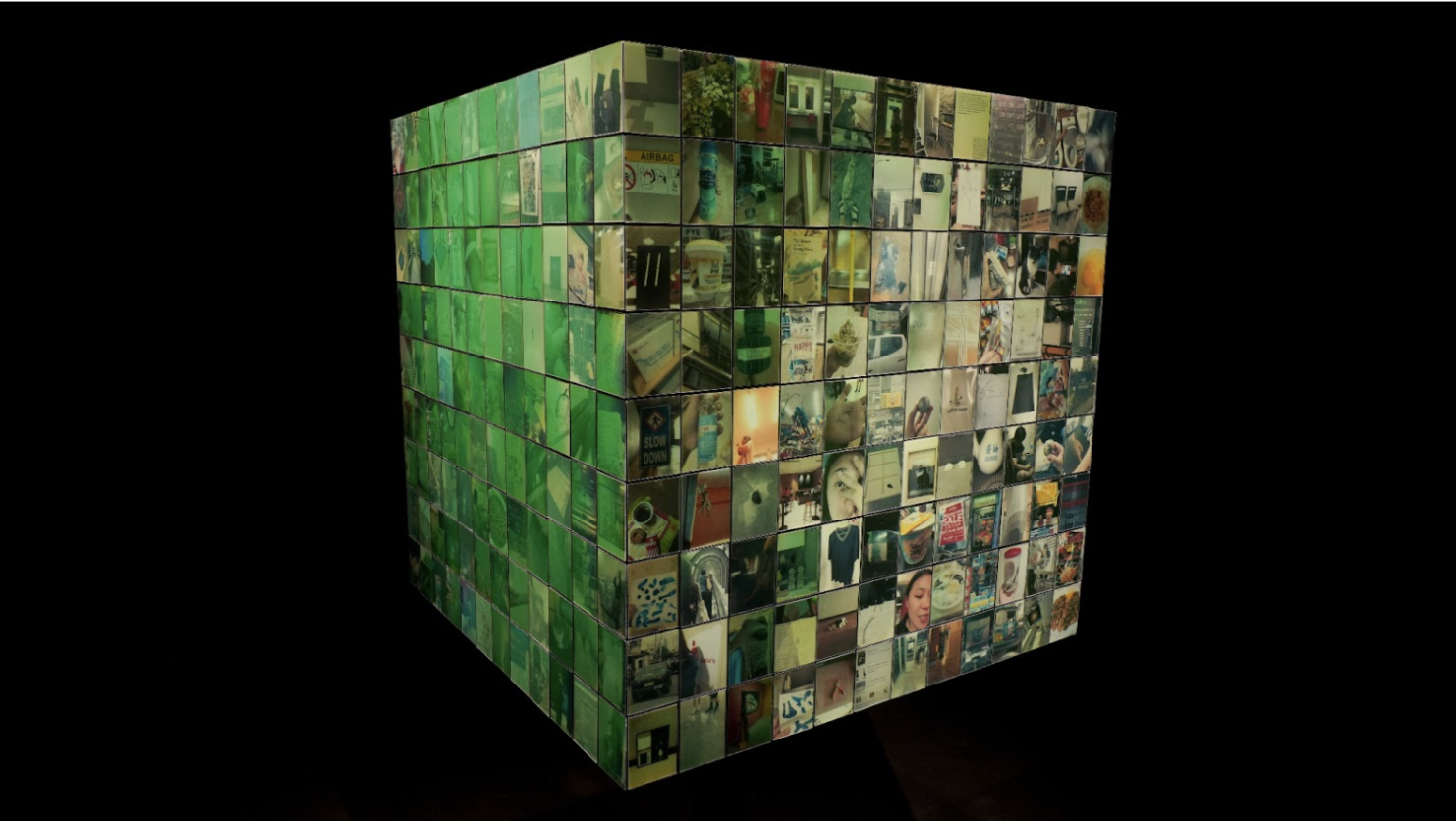

Her latest show, Free Space, which ran at Artinformal in Makati City last November, derives from the same experimental streak of her previous works but with an even more overt personal angle. Deploying a chroma green cubic structure framing various photographs—540 to be exact—Lee splayed the motley pictures out and incorporated them painstakingly into a singular, trippy sculpture. “[The] cube comprises 540 lenticular prints of photos captured through a smartphone camera, in portrait and landscape orientations: mindless selfies, half-finished food, proof of parcel deliveries, series of blurred shots, random snaps of pets, and hilarious road signs and vandalism,” the show notes states.

“The concept behind the work is an ‘existential crisis in the digital age’ so I wanted the work to feel surreal,” Lee tells me. Free Space, in effect, works as an offloading of images and memories, a digitized form of catharsis. But despite the anxiety impelling Lee’s process, the end result arrives serene and composed, each frame swathed in amniotic green. “I wanted an element of movement for the show which is why I made use of the lenticular lens. It functions as a screen — an analog screen.” It’s that screen that serves as a buffer between the tenderness of Lee’s memories and the unease through which they materialize years later.

“I feel like it’s relevant to me now since I’ve been experiencing moments of short-term memory loss,” she said. “Since the beginning of the digital age, we’ve become progressively wired to our devices that its possibilities always precede our comprehension.”

Throughout the artist’s career, Lee has been fascinated in unearthing these possibilities. By changing and challenging the material processes of her work, she has consistently found new methods of expression, openings to consider the self in relation to memories, digital spaces, and the sciences. For her, these openings emerge spontaneously, each exhibition a kind of timely self-interrogation. “I want to surprise myself more than I want to surprise others,” she remarked. Throughout her body of work, as with Free Space, Lee demands that we engage with our own daily perceptions, looking at each surface as a chance to reconnect with the wider world.