Featured in the eighth edition of the Asian Art Biennale, titled Phantasmapolis, one installation work stands as a series of trap doors, asking the viewer to partake in its trippy dimensions. The work features a wall with a door-like opening, and mirrors in the shape of footprints and a doormat. Printed on the wall is an island landscape, serene yet not quite right as the perspectives blur even more once you encounter a green screen copy of that same opening. In the strange logic of the installation, a portal gives way to another portal.

The biennale, a collaboration among five curators across three countries, looked at the concept of “Asian Futurism” as a jumping off point for interrogating cross-border interactions and mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic. Approaching Asian Futurism from this inherently political angle, the curators drew upon the surreal and the fictive as modes of registering the inequalities and unevenness of pandemic time.

It is through a consideration of that timescape, Arundhati Roy writes, that we begin to see the fractures in the “doomsday machine,” a system built upon prejudice, violence, and crisis. To this effect, the biennale invokes the image of a phantasmapolis, a blurring between “phantasma” and “polis,” as another way of imagining time during the pandemic, as straddling between the past, present, and future. Within the phantasmapolis, time bewilders the archive. The phantasmapolis activates a futurist way of seeing.

“While we often associate the archive with the past, it says much about the future and the attitudes we bring towards it,” Tessa Maria Guazon, one of the curators, said in an interview, reflecting on the provisionality of the archive as a structure.

Irradiated in this urgent light, the installation work ‘The Way Into Myself Featuring Conversational Adornments by Tanya Villanueva’ by the Baler-based artist Catalina Africa can be read as not only a reckoning with the self, but with what the self must endure in order to remain attentive, wonder-filled. A work of associative imagery, Africa’s installation is a snapshot of a mind simultaneously finding roots and forging a path where there seems to be none.

In Catalina Africa’s work, time serves a speculative purpose. Her work appears immersed in it, curious as to what it can achieve. ‘Rainbow Making Strategies 7’, exhibited in her 2019 solo exhibition at Silverlens Manila, features a suspended dried coconut shell, a clipboard filled with line drawings, and a metallic leaf. They are ordered vertically, as though waiting for light to hit each variable at the right moment, like a kind of divination exercise.

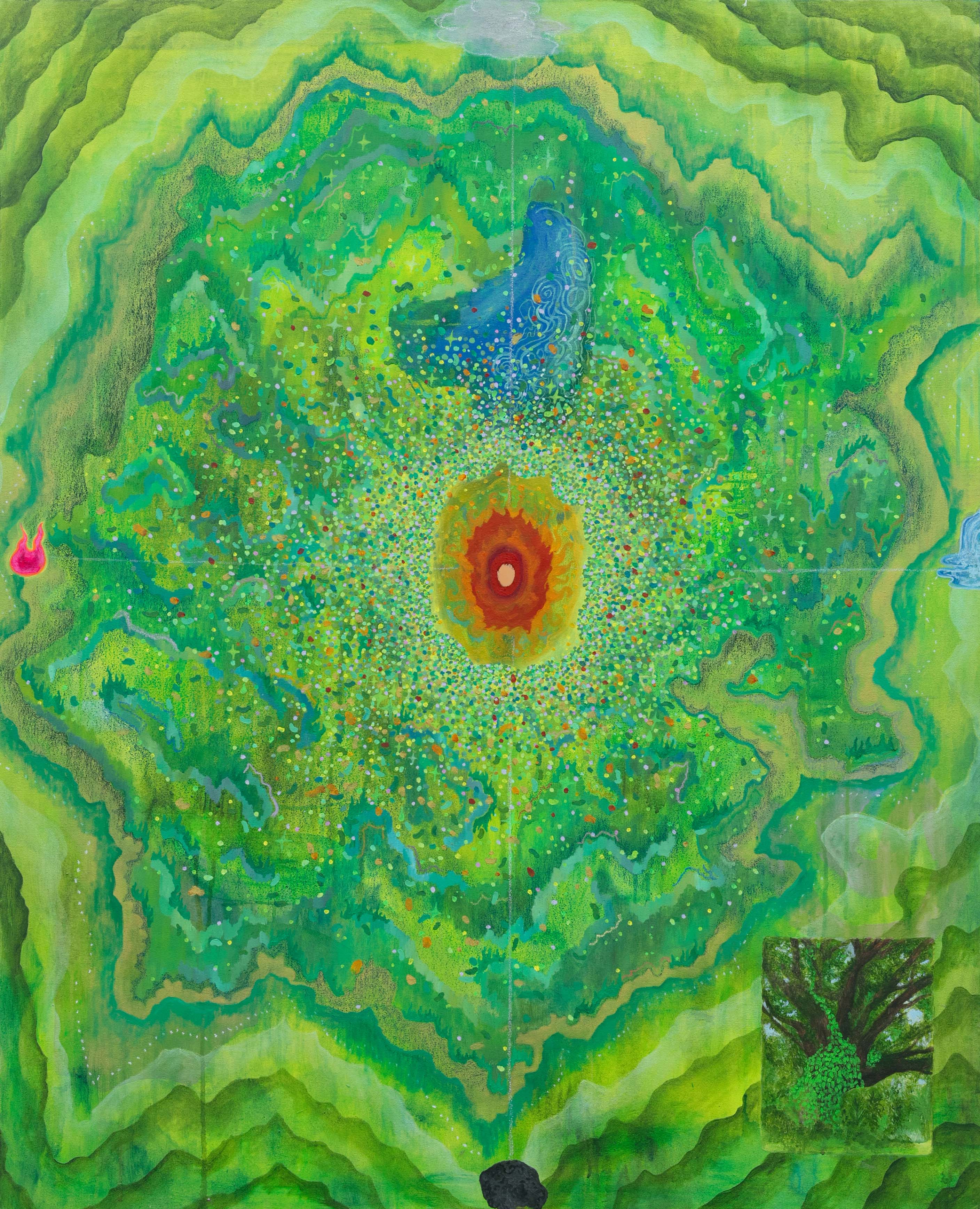

“I think most of my works reveal the interconnectedness of our inner and outer worlds,” she said of her artistic practice. Africa’s paintings are energizing landscapes, brought to focus by her understanding of the soft power inherent in regarding one’s interiority. Her paintings heavily feature portals, fleeting shapes and layers that engulf the viewers, bidding us to theorize on what may await us on the other side.

Although it could be tempting to read these paintings as mere navel-gazing experiments, Africa emphasizes that her work arises out of various collaborations, both human and non-human. “The energy of my work comes from the Baler landscape,” she told me. “I am a conduit to translate the language of nature.” This idea of the conduit recurs in our exchange as she explains how the natural processes of Baler, as well as motherhood, has made her more curious about where the self begins and where it may end, if indeed it does.

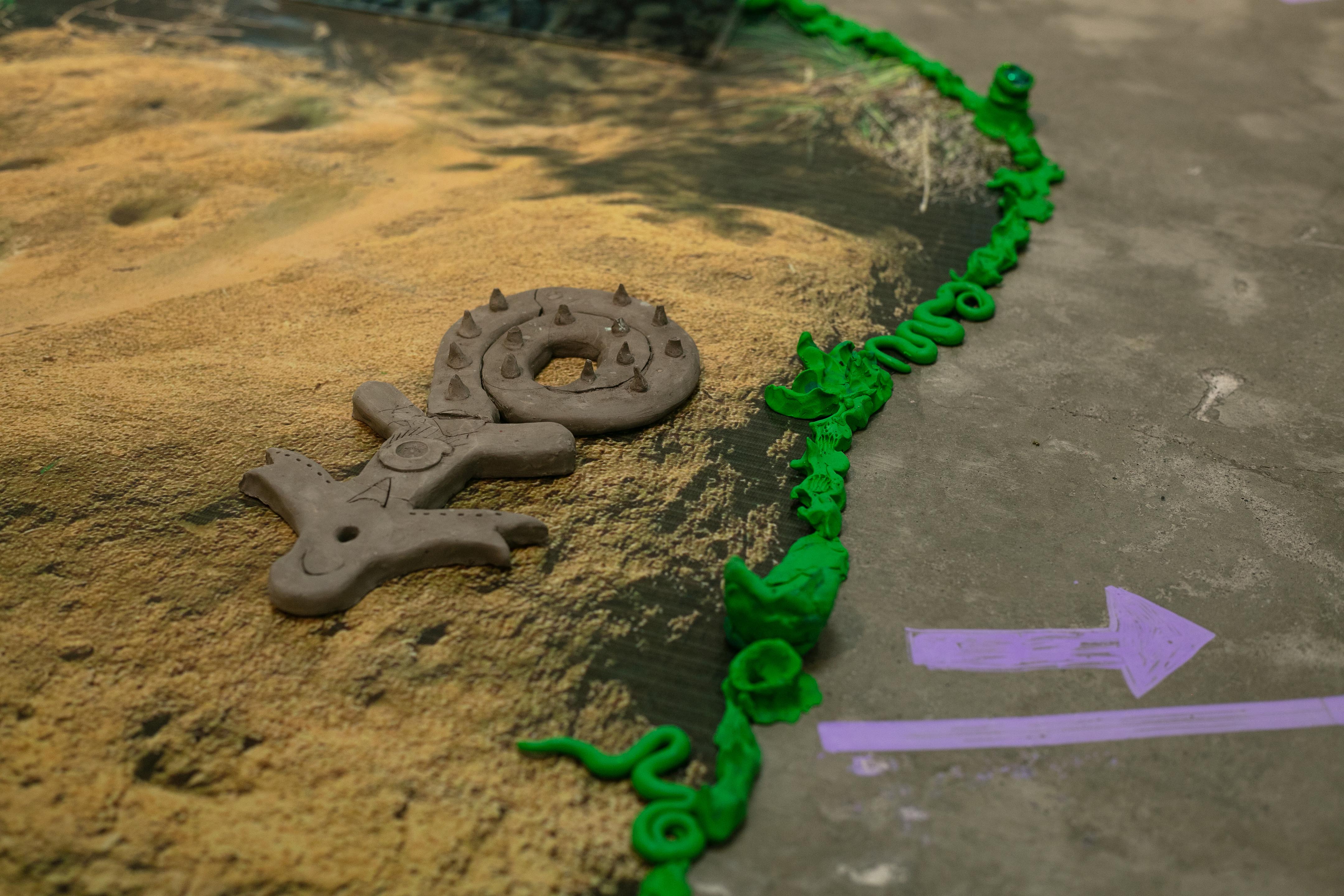

Thinking through the guiding inspirations of her latest exhibition at Silverlens, Shrine in the Shape of a Shadow, Africa recalls the shapeshifting nature of the earth: “There is a big mound of soil right next to a river where we and other locals frequently picnic. The mud mound is full of holes—foot holes and other holes of unknown origin. A lot of the kids slide down its face. I think of this mound as a sculpture, an artwork that is made by time, weather, the river, human hands and feet, animals, insects, etc.”

Searching for a way to apply this observation to her art practice, she said that “I wanted my body of artworks to be participative of these natural processes. I was thinking about revealing the processes of shapeshifting, or to revel in the process of shapeshifting, as opposed to displaying finished and complete objects.”

These states of in-betweenness, between inner and outer landscape, art and life, the made and unmade thing, prove to be invigorating. In the painting, ‘The Ability to Stay Close to the Source of Energy,’ Africa collaborates with her daughter Yana to create their own palette of blues, reds, and purples. At the center of the portal, we see the child’s handprint as circles emanate outward from the painting’s energy source. In its playfulness and its gentle evocation of waves, the painting pursues the title’s implicit question: what does it mean to stay close to the source of energy?

“They say that nature has its own language,” Africa reflects. “I feel I am studying what that means for me.” Motherhood, too, has its own language, one which goes in tandem with Africa’s language of art: “I envision that the source of energy for artmaking, and the energy source for being a mother, to be one and the same (not conflicting),” she wrote in an Instagram caption in 2021. “By becoming a mother, I have expanded my own definitions of what it means to be me.”

Her latest exhibition, Shrine in the Shape of a Shadow, evokes these persistent themes while deepening them. Patience, the willingness to let these works blossom and unravel over time as one surrenders to the inner and outer rhythms of life, seems to me one of the grounding dispositions that characterizes most of Africa’s works, and this exhibition testifies to that practice. “I think the most poignant shift in these current works is the realization that I may be a portal for other voices to pass through and be heard,” Africa contemplates. “That my works do not come from me, that I may actually be the earth asking itself, ‘who am I?’.”

The centerpiece of Shrine in the Shape of a Shadow is an installation work that appears to envision a circle of life through an assemblage of found material. The exhibition catalogue lists, thrillingly, the elements which make up the work titled ‘Revealing the processes of shapeshifting, participating in the processes of the earth’: “tarpaulin, unfired ceramic clay, stone, modeling clay, sticker, acrylic sheet, charcoal, glass aquarium, sintra board print, found corals, candle, mirror, cave sculpture, liquid chalk.” There’s a strange pleasure in imagining how these objects and materials in the list corroborate and expand upon the worlds of Africa’s making.

Artifacts, shards, flowers, footsteps, a mound of dirt. The daily labor of seeing. A wash of color. For Africa, all these miniature and passing things are not questions which await solving, but the answers themselves. Though not necessarily providing comfort or security, these are the little things which form a conviction, inviting us to forge a language between our own inner and outer worlds.

Sean Carballo is a writer and undergraduate from the Ateneo de Manila University.

Images courtesy of the artist and Silverlens.