As if to emblematize the four-year hybrid preparation for the four-month-long Imelda Cajipe Endaya: Pagtutol at Pag-asa retrospective in CCP, Conversation with Material: Artist’s Talk also facilitated physical and online interactions among the curators, artists, and the audience. In their first public program last September 24, curators Lara Acuin and Con Cabrera shared their ideas and processes on how they tackled this huge undertaking. They anchored their elaborations after showing snippets of their recorded interview with the artist, who joined the Q&A afterward in Zoom.

Following health and safety protocol, a small crowd was allowed to attend the talk at CCP Main Gallery. I was one of the few people who attended it in person. Exactly a week after, I got a chance to interview the curators (albeit virtually at that time) where we expanded the points from their talk on co-curating the exhibit, creating the ‘Redux’ pieces, archiving and conserving, and finding the strength to refuse and to hope in these times.

On curating

In terms of the length of experience in co-curating an exhibition, the two curators are on different sides of the coin. It was Lara’s first time while Con already has several engagements in the past. Despite this, they have a similar view on collaboration: it works best if you cannot identify who made a specific contribution. In Lara’s words, it’s beautiful when you “come up with a third thing that is not you or the other.”

Considering the pragmatic side of working with an institution, Con clarified that their roles are clear in terms of their contracts. Con’s main function as a curator is on designing the exhibition, while Lara’s is on writing. Even so, they always consulted with each other in their assigned tasks, whether big or small. To make sure that their decisions were within the possibilities and boundaries that CCP can provide, they also sought advice from Rica Estrada and Neli Go, Officer-in-Charge of CCP VAMD (Visual Arts and Museum Division) and their Project Coordinator, respectively.

Having a dependable synergy between the curators and their collaborators was important as much of the preparations had to be done remotely. It was pre-pandemic in 2019 when they were informed about the exhibition. So when the lockdowns were enforced in early 2020, it introduced a physical impediment – suddenly, they couldn’t go out to see the works, space, nor the artist in person – so they had to work with what they had gathered before the strict quarantine. Lara was thankful that they were able to digitize materials from ALiWW (Ateneo Library of Women's Writings) and CCP at all, as they relied on these while working in the safety of their homes.

Planning the space had also been an evident challenge. When Con saw the CCP Main Gallery in person during the Thirteen Artists Awards exhibition, she said that it disoriented her because the space was not what she had imagined. It reminded her that as a curator you must be open to changes, you must not be a “control freak,” recalling the title of Karen Ocampo Flores’ article “Etiquette for Curators — and for all other budding control freaks in the art scene.” Con emphasized that curatorial work is not done step-by-step: there is always fluidity in the process.

Embodying the unexpectedness of the process is their long break from working on the exhibition. Since it became clear that it would not happen in 2021, they stepped back from it for months. The curators appreciated how the interlude allowed them to be reflective. It also granted them space to grow as individuals. When they finally had a definite schedule for the retrospective, they revisited what they did with fresh eyes. Lara admitted that there is also a challenge in getting back to it right away after letting it rest for too long.

Given the expanse of the retrospective, allocating active and restful times had been essential especially since they had to make careful and thoughtful decisions on which artworks to exhibit that capture the spirit of Cajipe Endaya’s expansive artistic practice from the 1960s until the present. In their talk, they already shared that the artist gave them a “wishlist” of the works that she wanted to be included. Con surmised that since Cajipe Endaya is also a curator, she picked the works in a way that a fellow curator can make sense of it. Both Lara and Con pointed out though that they were not given instructions or themes. The artist allowed them to be creative with the list. For them, it was not difficult to uncover its essence because the artist had been very consistent on the ethos of her life and art: “babae at bayan” (the woman and the nation).

From the list, they formed loose categories such as women in history, care work, imperialism, and war, all of which overlap. These thematic markers are not physically-identified in the space, which is a conscious curatorial decision for them. Going by the theme and not by time period is also a choice to veer away from linearity which has historically been associated with masculinity and grand narratives.

The nonlinearity is also exemplified by the curved flow of navigating the site of the encounter. They took inspiration from caracol (Spanish word for snail), the subject of Cajipe Endaya’s exhibition in 2019, and Curved House, a show that Con curated in 2012. In designing the space, they also considered the historical burden that only a few female artists have mounted a retrospective in CCP. Con imparted that CCP is also conscious of that, so they are trying to remedy the problem.

While a prolific artist, Cajipe Endaya is similarly productive in writing her contemplations. In one of her writings, Lara found the key to the first keyword in the title when she came across the phrase “art of refusal.” After long deliberations with the team, they settled on “pagtutol” because they felt that the word was active translation-wise. The artist suggested to include “pag-asa,” as hope would make it feel more whole.

On artmaking

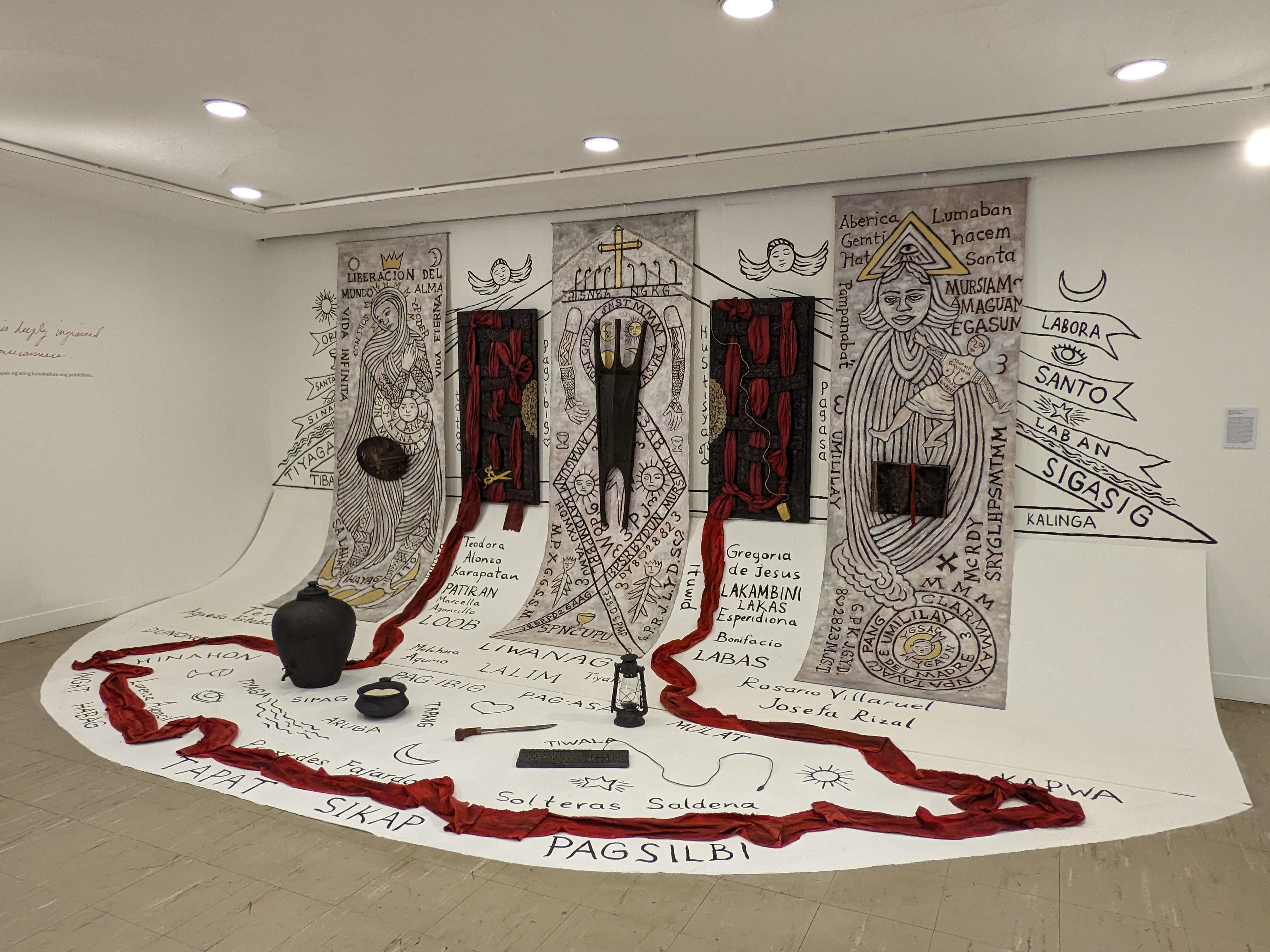

The retrospective featured installations – which have titles appended with Redux – that they had to rebuild because they were site-specific works. There were long discussions and consultations with the Cajipe Endaya at the start, but during the process of recreation, she encouraged them to be creative and fully trusted them. “What you think is best,” the artist kept telling them.

Aside from the artist, they also acknowledged the crucial role of Neli Go, their Project Coordinator, who coordinated with all the institutions and individuals they loaned works from. For those that they were not able to borrow, they had to recreate, such as the missing paintings in ‘Kapatiran ng Lakambining Maybahay Redux.’ They also commissioned muralist Auggie Fontanilla to assist them. Some objects were bought, like the tapayan and palayok, and some were constructed like the itak. Con was in awe with the Production Department that made the itak look realistic.

In the huge airmail envelope that the Production Department made for ‘Signed, Sealed and Delivered Redux,’ Con divulged that they forgot to specify to render the red and blue border in a more painterly manner. It was a situation where her skills as an artist came in useful as she had to repaint those parts. The long trail of red cloth in ‘Lakambini Redux’ would also have to be repainted by Con and CCP VAMD intern Rada Krishna Depante.

The mismatch of the cloth’s redness with the reference material only became visible when it arrived at the white exhibition space. When they asked the artist if they can paint over the fabric, she was nonchalant about it. For Con, it was an example of how Cajipe Endaya practices feminism through art. She does not put an object as a component of artwork on a pedestal the way the artworld imposes value on it. Whatever will be returned to her will have a new life in her future works.

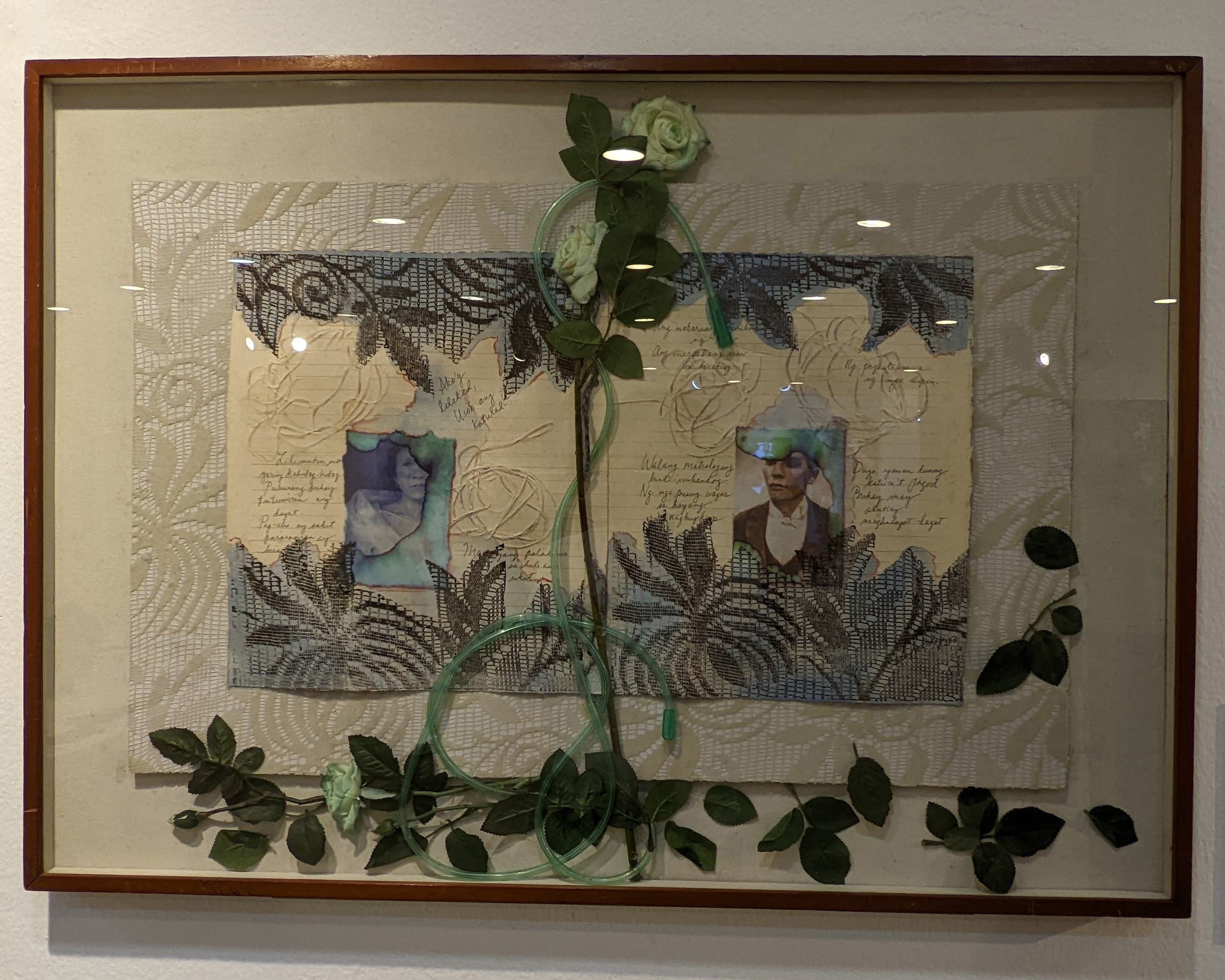

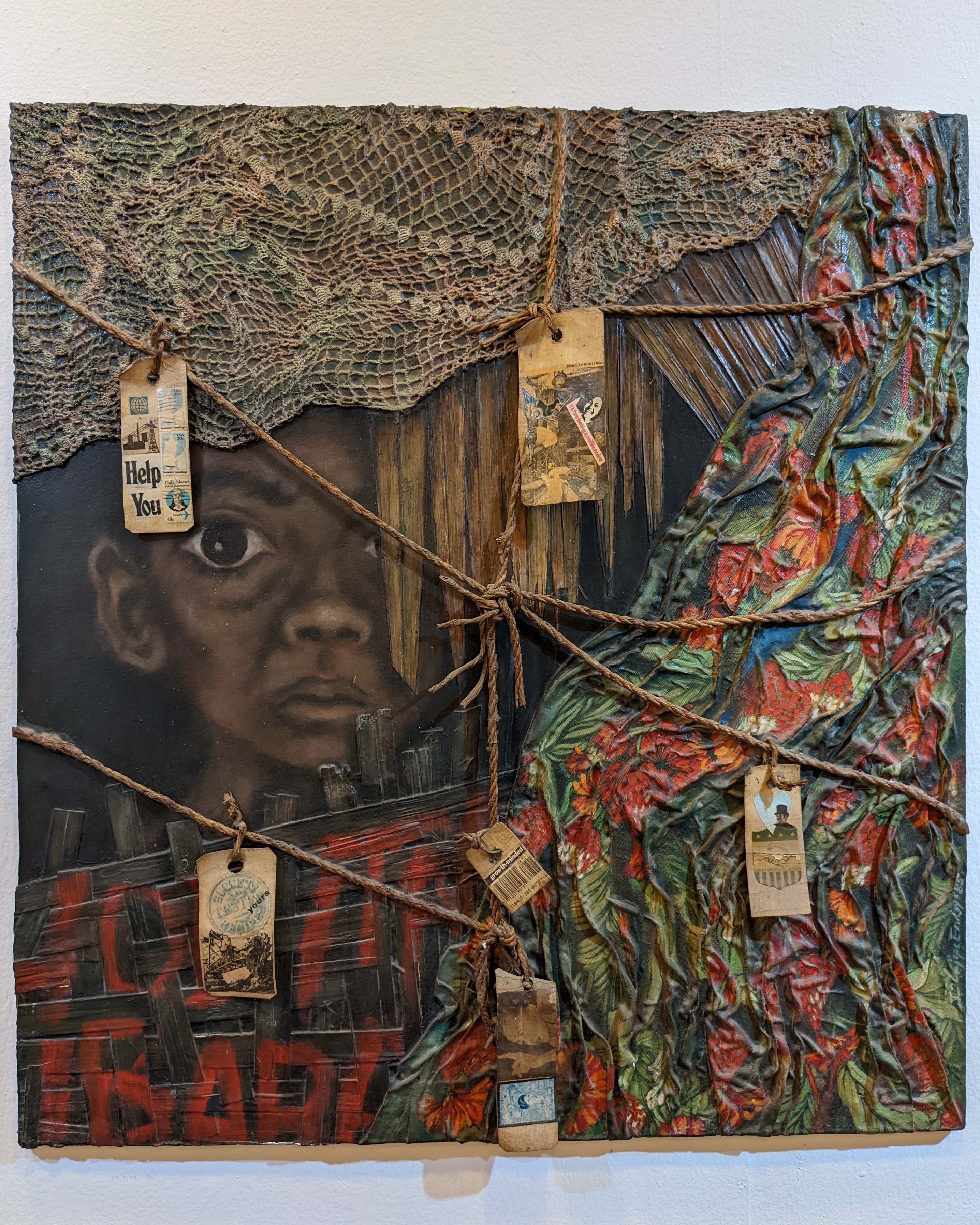

During their talk, they also touched on the afterlives of the artist’s works where Cajipe Endaya shared that some luggage in the 1995 ‘Filipina: DH’ installation were still used for its actual purpose. Ruminating on the term “afterlife,” Lara felt that it might be more appropriate to call it “continuing life,” a thought provoked by something she read recently on colonial photography. As the objects change in appearance, use, and application, their lives continue. While some of Cajipe Endaya’s works have been described as an assemblage in a way that recycles and ossifies things, Lara opined that they are rarely ossified: they had undergone and will undergo reincarnations.

On archiving

In maintaining a database of her artworks and even in simply making duplicates of articles, Con observed how archival intuition is manifested by Cajipe Endaya. This mindset is invaluable especially with the archive as grounds of previously unrealized meanings, discovered and formed in the future by researchers who will engage with it.

The archive is also a reflection of its custodian, which applies to individuals and institutions. Con exemplified that Cajipe Endaya stores clippings of newspaper articles that interest her which implies how she thinks and what she pays attention to.

Since an archive is meant to last for a long time, proper maintenance is imperative. This includes the conservation of materials. During the lockdown, the curators along with Cajipe Endaya and art handlers in CCP joined a mechanical cleaning workshop with conservator June Dalisay. Since the retrospective featured works that were created decades ago, there were paintings that they had to clean and repair, which they only did after seeking consent from the owners. Seeing the state of some of the artworks that they borrowed, Con realized how very little education we have on conservation, even for serious collectors and curators as custodians in the artworld. It’s a sad reality, but it’s a challenge that we should be actively working towards.

Lara agreed on how artworks should be taken care of in the long term. She also posited that some of Cajipe Endaya’s works presented a microclimate framing with how natural materials such as twigs and leaves are incorporated within.

On refusal and hope

Taking cue from the last query thrown to Cajipe Endaya at the talk, Lara and Con also faced the question: Saan niyo nakukuha ang lakas ng loob na tumutol at umasa sa panahon ngayon? (Where do they get the strength to refuse and to hope nowadays?)

Both the curators expressed that they were hugely inspired by deeply engaging with the works of Cajipe Endaya (whom they referred to as “Ma’am Meps” in the entire interview).

For Con, seeing and working in-depth with the art of Ma’am Meps made her realize how their advocacies align. It further sparked her conviction to hold on to them and continue fighting. Even if there are hardships living in this country, what gives her hope and motivation every day is working towards producing more scholarly work or curatorial projects that provide visibility to women artists like Cajipe Endaya.

For Lara, she can sometimes see herself in the representational works of Ma’am Meps, those that feature faces. In that, she feels that she has a karamay, where in her words, “they’re for you and they’re with you.” She’s also grateful for the one-of-a-kind collaboration with Con and with the team, the friendships that formed, and the openness and encouragement they received from the artist throughout.

The exhibition will have its second public program ‘Pamumulaklak: A Gathering of Women-Citizens’ tomorrow, October 22, 2022, at the CCP Main Gallery. The event convenes women artists, advocates and activists to share about past and present engagements and cultural work in support of issues affecting marginal women that resonate with Imelda Cajipe Endaya’s subject matter and advocacies throughout the years. For more information, please visit CCP VAMD on Facebook and Instagram.

Lk Rigor is currently pursuing MA Art Studies in UP Diliman. Aside from being a curator, she dreams of becoming a cat lady someday.

Images courtesy of the writer.