Editor’s note: The following text, a series of letters, is a timely expression of concern (as well as creativity), coming at a time when discourse has become marred by discord and disinformation. When artist and writer Lyra Garcellano approached me with her pitch, the idea had been to conduct an interview with fellow artist Lec Cruz, with whom she shared Finale Art File’s gallery space as part of two concurrent shows that ran from July 15 to August 8: the group exhibit All Like Hours and Cruz’s solo show Hello, World! In reflections on their personal artistic process, the artists invite, perhaps enjoin, readers and viewers of art to engage in the active exploration of the past, to take stock of how the course of history shapes our understandings of present realities and shared experiences — from how we find and move in space, to what we value.

The ekphrastic outcome of the artists’ exchange over email, is a testament not only to the potential of art writing in supplementing historical consciousness, but also to the power of an open dialogue to reconcile criticality and discourse: to evolve ideas, find answers, and, perhaps more importantly, raise the questions that keep the conversation going.

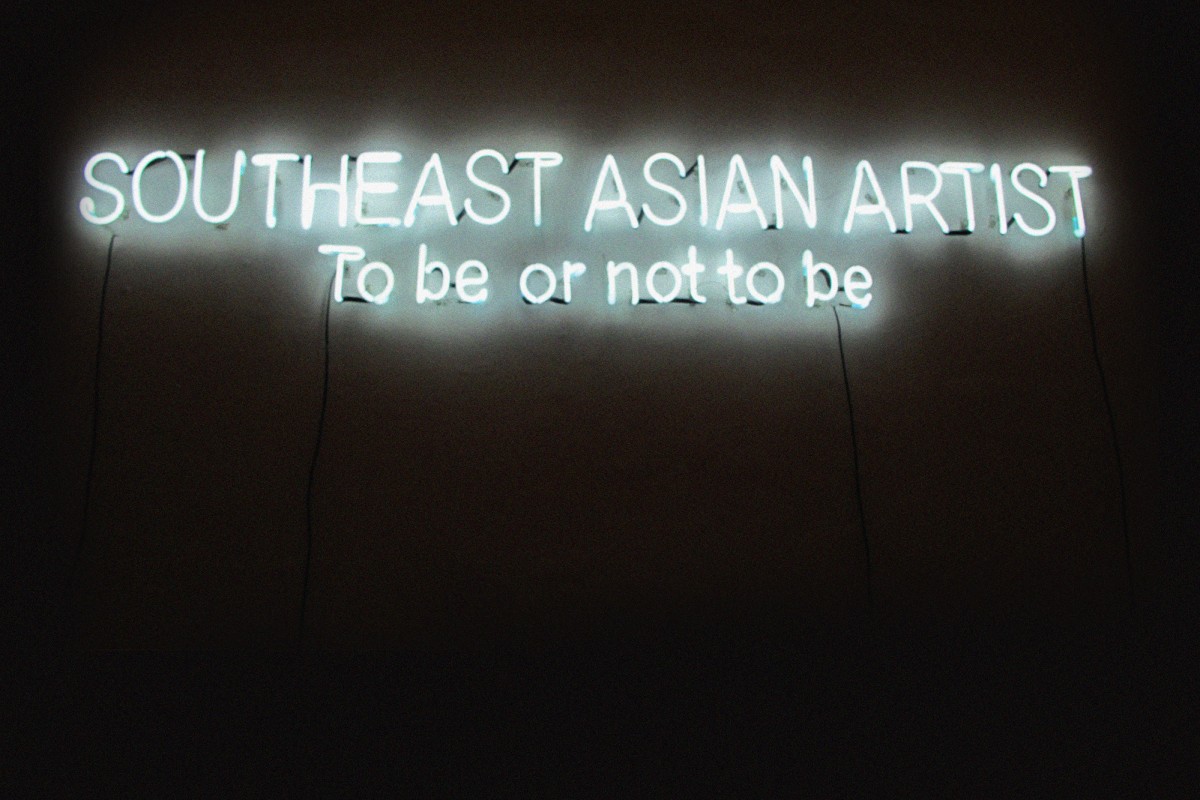

Banner image: Lyra Garcellano. Southeast Asian Artist: To be or not to be, 2018, part of the artist's Art Fair Philippines presentation.

Hey, Lec.

Cleanly dissecting the studio-to-market practice is complicated given that we both operate within gallery systems that foster our respective works. So, when I am asked how I keep my works “current” regardless of the subject matter I am working on, I feel such a question alludes to that unavoidable attachment of art meaning-making to the rules of the fickle market.

On these terms, I think about the happy, messy — yet ethical! — compromises we each make in order to maintain positions that will allow us to "perform" in real-estate spaces (and before an ambivalent audience). At the onset of the pandemic, weren’t we all forced to consider alternative ways to function outside the then-closed white cube (and all its permutations)? NFTs?

I assume there’s always that voice in our head pressuring us to adapt to (art) languages that are regarded as "new," digestible, and, thus, translatable into different modes of capital. Aspects of career-retention and/or daily-life security are constant triggers (or deathly reminders) — our precarious (material) state ever hounding us.

Some time ago, I was asked where I located myself in the art landscape. My jaded response was an acknowledgment that I didn’t have much political currency on the table. Displaying no technical spectacle in my works and having barely-there communitarian value, I’ve labeled myself as a “wrong” Asian, ergo, always standing on shaky ground in the so-called international artworld. Even in the local arena, my social citizenship feels wobbly.

Regardless, I participated in platforms that welcomed my existence. I nurture(d) the hope that the reception of my works will equal viewers re-assessing their perception of life.

Around 2018, I ventured into questioning National Artist Fernando Amorsolo’s visual tropes. At Art Fair Philippines, I debuted Tropical Loop — a two-channel video featuring myself in a Sisyphean cycle of labor relating to this prickly rural idyll. The video was accompanied by a neon sign: ‘Southeast Asian Artist – To Be or Not to Be.’ I wanted to engage the viewer and ask: To what capacity can the act of storytelling be presented if our educational system is stuck in an environment that’s muddled and institutionalized in western-inclined persuasions?

John Berger introduced the notion of representation and the male gaze; I zeroed in on western eyes gawking at the exoticized Philippines. Story of our lives!

Truly, artworks do not occur in vacuums. And our creative productions stem from a desire to offer something that goes beyond potboiler categories. (Well, that is the dream.)

Thematically, I scrutinize canonized narratives — the “normalized” stuff — that are fed to us (and the pipelines through which they are maneuvered). Lately, my research has led me to re-imagine the optics and mythmaking of 1900s Philippine Carnival Queens.

Without compunction, I hold to the idea that there is this massive urgency — and, thus, responsibility — for us to prevent and oppose historical revisionism in our country. And yet, here we are submerged in a type of cultural ethos that cultivates a crowd whose attention span is, maybe, 10 seconds or less.

Granted that the social, financial, and technical admission to platforms is the least of our worries, how does one initiate critical conversations, especially in environments where discussions on art, culture, and history have been industrialized and (often) simplified into appraisals of value for money?

When institutions have firmly put into effect the preferred knowledge production and transfer championed by the powers that be, the overarching question is:

How does one carve out space?

From

Lyra

Hey Lyra,

Ours is a culture of “forgive and forgets” that keeps us from being haunted by the past and traps us with daily state of affairs because stories of everyday struggles for most of us outweigh the histories written in texts. We summarize our past with materiality, the tangible mementos and tokens. The Spanish occupation of more than three centuries are compounded in our sign posts and monuments used as landmarks; the American rule of almost five decades is confined within their air and naval bases; and the Japanese atrocities are remembered at the sight of some obelisks. As long as the majority of us have empty stomachs, only the privileged and those with cultural capital will be able to appreciate our collective story.

I view making art as an opportunity to be a part of this cultural work, of the art world as a venue to shape and re-shape certain views that can augment our awareness of our history and pinch into our sense of introspection. In my 2016 exhibition at West Gallery, entitled The Sun sets in the West, I grounded my works on what was happening in our society at that time with our recent history under Martial Law. I made portraits of yawning political personalities of that era and re-imagined their faces as being bored and uninterested with the narrative that facts about history are being questioned and undermined as if this has happened before and there is nothing new about it. I was aware that making those works would add up to the morsel of physicality we have about the past, partly a demagoguery, for the lack of a better term, and partly an idealistic pursuit.

I guess that is part of the compromise an artist should make to be able to contribute to meaning-making — to appeal to someone else’s emotion. There is a fine line between pandering to social issues and making meaningful art without reducing the viewers’ capacity to understand what we are trying to explore. Of course, there is no denying that art-making can be a masturbatory wormhole where we try to navigate our individual nuances, understand ourselves better, and hope that someone else feels the same way we do.

Given how important the materiality of our works is in fostering an idea to our viewers and the limited time that they can be seen in the galleries, bridging that gap between retaining their context or “aura” and getting them exposed to the public is very challenging, especially during the pandemic. Once we post a picture of them on social media (socmed), their meaning can easily be hollowed, and depending on how fast or what state you are in when you consume that image, their presence may easily be lost. So, presenting them in an online sphere is in itself a “skill” we have to adapt to, mainly because of what you pointed out that it is a 10 second or less. The socmed algorithm gods have yet to grant me their favor without the need for me to expose my introverted self too much.

In making my most recent exhibition Hello, World!, I wanted to explore and exploit developing technology by using Artificial Intelligence (AI) in creating seemingly “novelty” images. Since it has been prevalent with NFT creators and AI itself uses the millions of images we have uploaded over the years to create new ones, I find this idea appealing like a pile of cakes full of questions inside of them, asking to be consumed. Does using it indirectly democratize art-making and meaning-making? Does art become more potent when a part of it comes from the unknowing collective consciousness of society? How much of the images will be remembered by the public bound in a culture of “forgive and forget?”

———

Lyra Garcellano’s research centers on the investigation of art ecosystems, and art history, and her output is often presented in installations, paintings, moving images, comics and writing. She is particularly interested in how prevailing economic models impact artistic practice. She is a graduate of interdisciplinary studies of the Ateneo de Manila University and holds a BFA degree in studio arts and an MA in art theory and criticism from the University of the Philippines.

Lyra is the creator of MIKI BLUE toons and is also a co-founding editor of TRAFFIC, and the Teaching Exhibitions zines.

Lec Cruz studied BA Philosophy and BA Fine Arts major in Painting in UP Diliman QC. He started exhibiting in 2010 and have had ten solo exhibitions since 2015 in galleries such as West Gallery, He has since been exhibiting with local and international galleries. He has also been writing exhibition notes since 2015, working with artists and galleries in and out of the the country.