The seed for The Rose of Manila started taking root when Alex Westfall was just a pre-adolescent coming of age in Los Angeles, several thousand miles from the place of her mother’s birth. As a young girl, she discovered that in the 1970s, her maternal grandparents who lived in Manila — employees covering current affairs for GMA at that time — had to exile themselves as a result of expressing dissidence against an authoritarian regime. “A lot of my work stems from the existential question ‘How did I get here?’,” Westfall reminisced. “It’s just something I’ve been thinking about for as long as I can remember. What would have happened had this dictatorship not happened, would my mom be in Los Angeles, would she have still met my dad, would I still exist?”

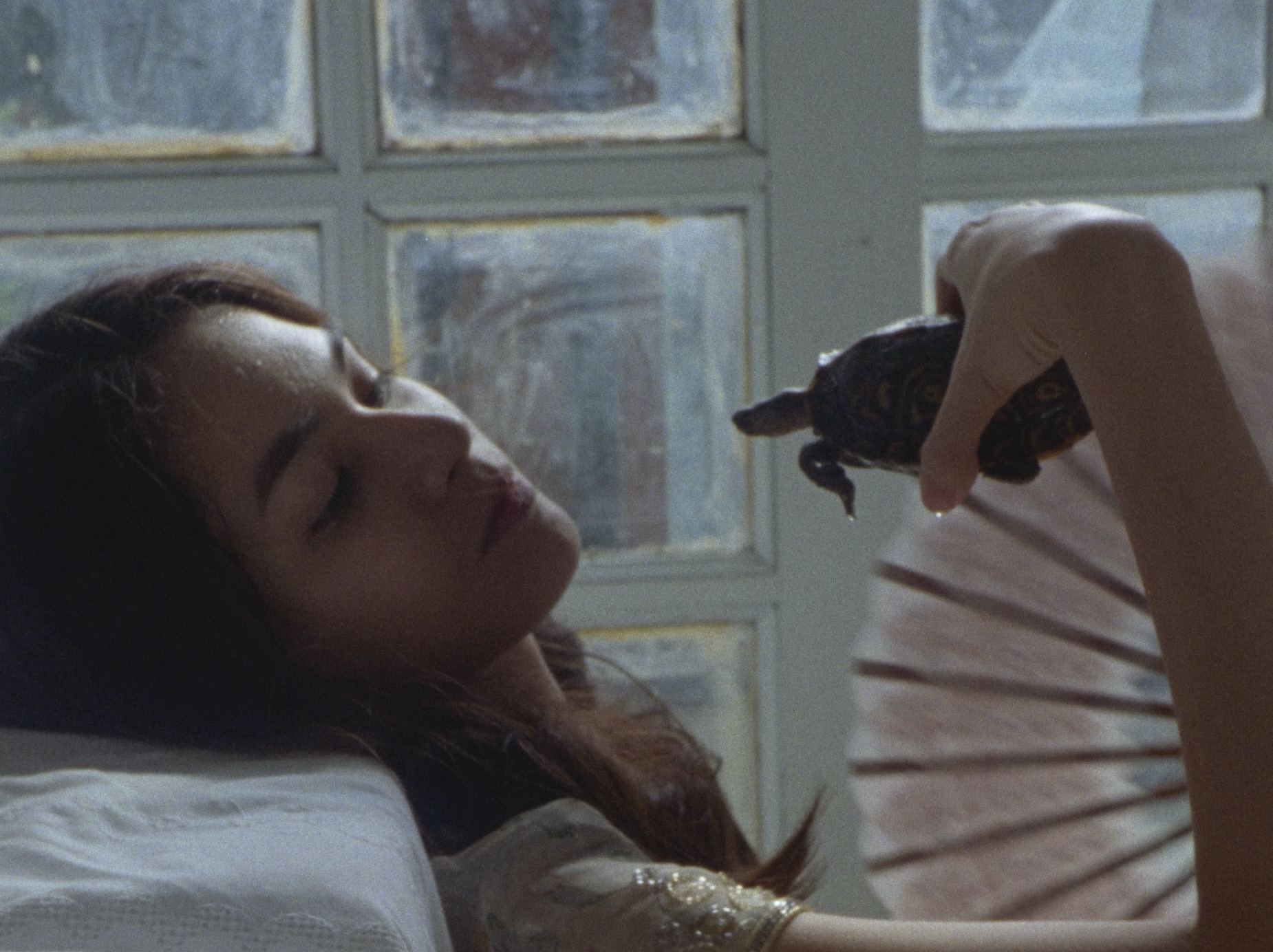

“A light test for Polly featuring Imelda the tortoise.”

Westfall, who studied Modern Culture and Media at Brown University in the small, coastal city of Providence, Rhode Island, began delving into this period in Philippine history, a melding of both her personal and historical investigations. During this time, she came across works that became instrumental to her short film, such as Ramona Diaz’s Imelda, a 2003 documentary film about Imelda Marcos shot in 16mm and the biography written by Cecilio Arillo of the same title.

Every artist knows that the excavation of their personal histories, that inevitable inquiry into their own provenance, is an exercise in tilling soil rich in material, breaking up the chronology of their lives for new questions to take root and emerge. For Westfall, it was a matter of “asking questions that I’m asking of myself through the life of another person.”

It was through her research that she came across the contention surrounding what really happened during the 1953 Miss Manila beauty pageant and how there came to be two representatives for Miss Philippines, one of which was Imelda Romualdez, before she became Imelda Romualdez Marcos, the dictator’s wife. On March 3, 1953, contrary to the original decision that crowned Norma Jimenez as the winner, Manila Mayor Arsenio Lacson named Romualdez the official representative of Manila in the Miss Philippines. In the end, both women attended the presentation of candidates for the Miss Philippines contest.

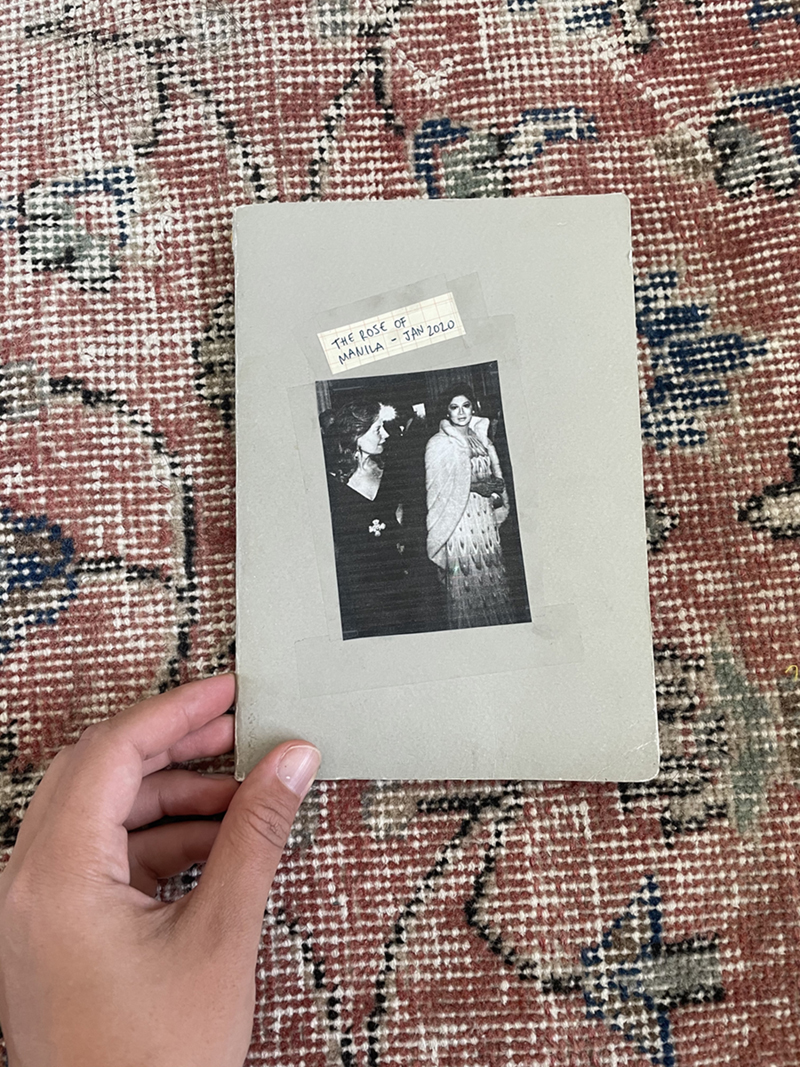

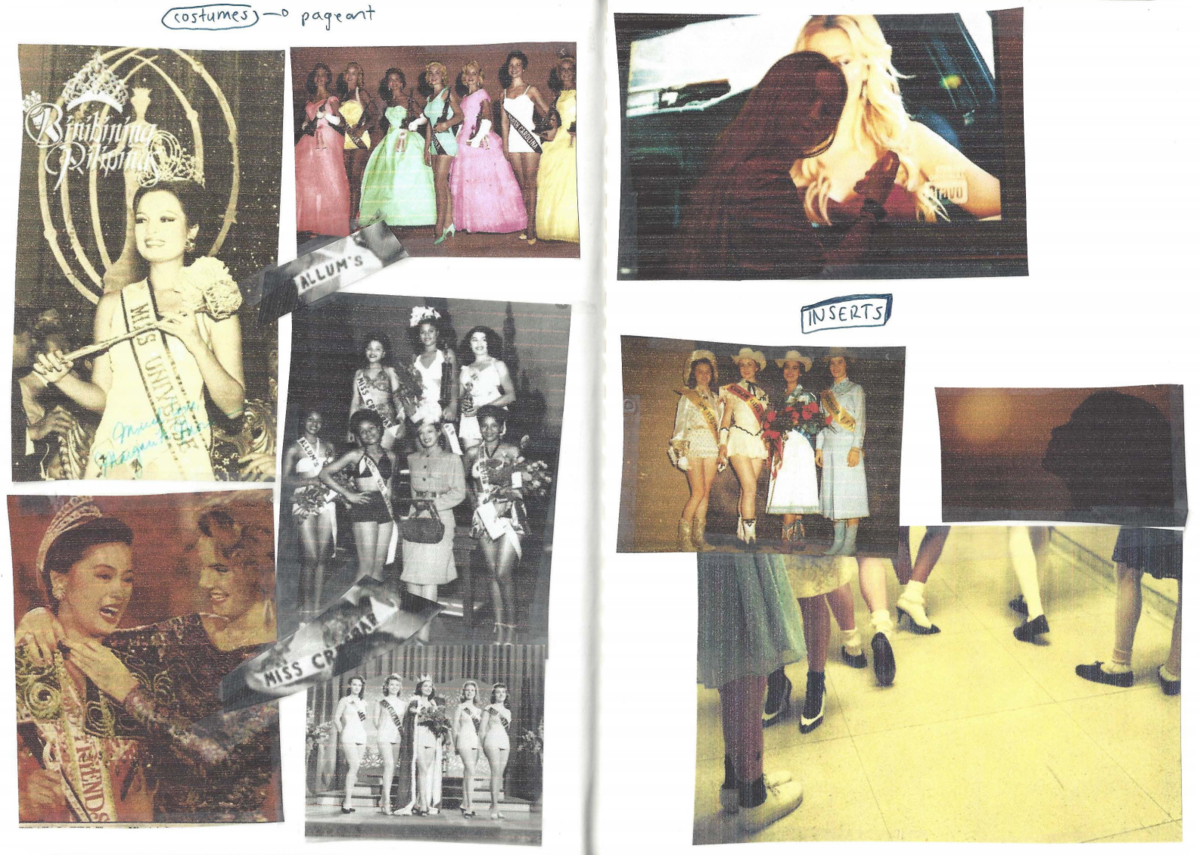

Newspaper clippings of the 1953 Miss Philippines Contest. Images source.

Rumors swirled; newspaper clippings from that time and a first-hand account from Imelda herself in Arillo’s book contradicted and further muddled the truth surrounding the last-minute decision. “It was the controversy that gripped me because it’s such a marker of the fact that maybe she was already that kind of person before Ferdinand swept her into politics and power… I was interested in how there were multiple narratives revolving around the story because I feel like that’s such a metaphor for how history is remembered. How media, images, text can completely shape the way we see the history of our nation.”

After the EDSA People Power Revolution in 1986, her grandparents had settled back into their old home in Manila where Westfall still comes to visit every summer, and where a new generation continues to be threatened by sins of the past with the possible re-election of the dictator’s son in this year’s presidential elections.

A fertile collaboration

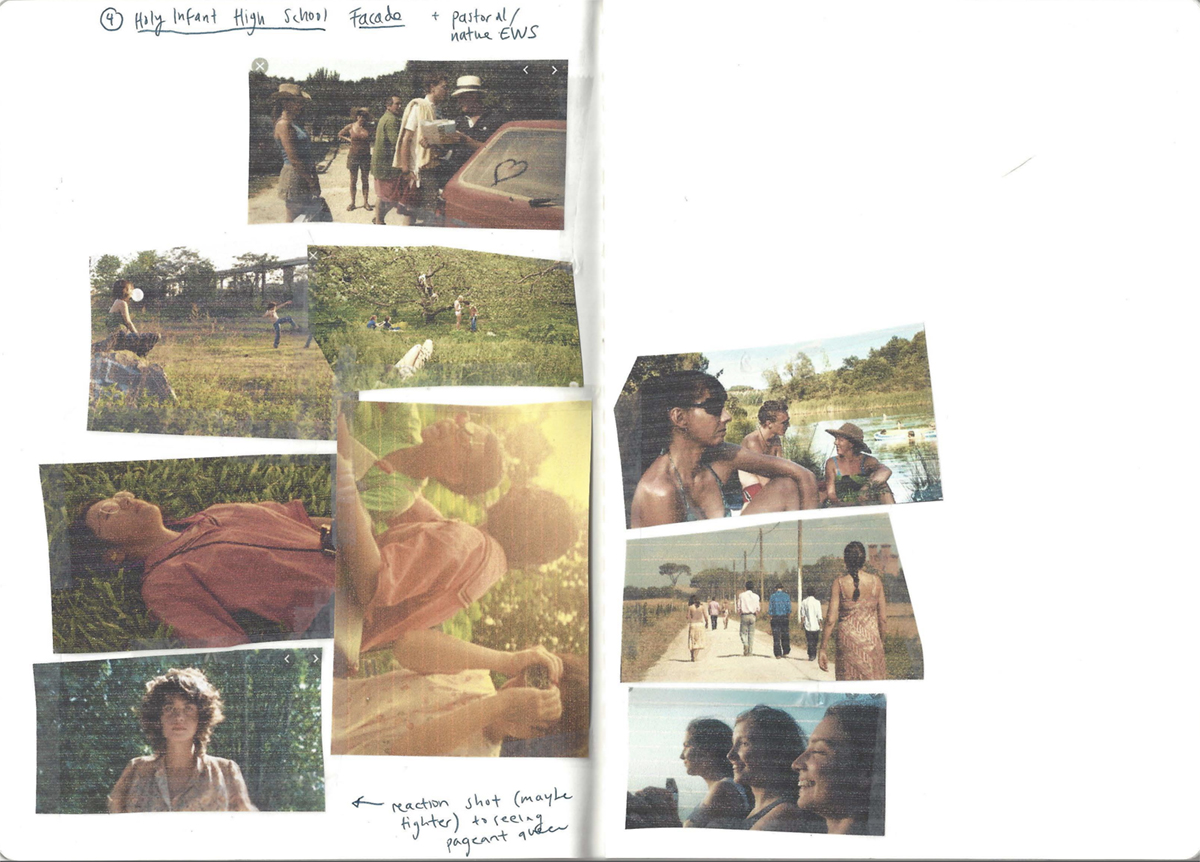

Most of the short film was shot on the sparkling coast just south of Cavite and a garden in Antipolo that Westfall’s Filipino mother used to visit as a child, hoping to evoke the Leyte province where Imelda spent her childhood and where she lost her mother to pneumonia at the age of eight. “I think a lot of contemporary films based around or set in Manila have a dark, greenish, 'urban jungle' feel. I am intrigued by these aesthetics (and love the films of Marilou Diaz Abaya and Lino Brocka in particular) but I also hope my film contributes to the visual archive of the greater Manila area, portraying it as somewhere green, lush, dreamy.”

Film title card.

“A local church in the city of Antipolo permitted us to film the choir practice in their scene before their first service at 9am.”

Armed with a 16mm Bolex camera borrowed from her university and a 9-page script (the dialogue, both in Filipino and Waray, were translated by Westfall’s mother and her colleagues), she shot the film right after the Taal volcano erupted in 2020, where she was still “determined to depict how the light feels in the Philippines.” However, after a few days of shooting, she shared, “I was met with imagery that was blurry–and therefore, unusable. The pressure plate, which is what is meant to connect the lens to the camera body, wasn’t properly fixed. So, I cried for three days. Thankfully, Mo (the cinematographer I collaborated with) had the foresight to film backup footage… It was a little Canon handheld camera, I believe… I went back and found the handful of 16mm shots that were in focus. I cut that in with the digital footage and went back to my advisor. Together, we thought, Wait, this is working. By placing old and new technology in the same space, the form was serving the content—because the story is so much about multiple timelines occurring at once, and looking at someone’s early life through the lens of the present.”

The film’s visual language is informed by Westfall’s background in photography and image-making. “I primarily see film as a visual medium. If I can tell a story visually I’d rather do that than convey it through dialogue… It’s such a great challenge that I try to set up for myself because I think you can reveal so many subtle things just through action and expression,” she said.

In the short film, you get a sense of her photographer’s eye. The Rose of Manila forms a sun-tinted mosaic of long atmospheric takes and languorous camera movements. It’s a rabbithole of glitter, metallic foil stars, dreamy florals while attending to a young woman’s self-obsession and craving for fame. It’s far from romantic: her world is distorted by a tropical cyclone and a heavy lack of decadence. It’s an audacious debut, one that refuses to humanize an all-too polarizing figure in Philippine history. Imelda’s character may seem vulnerable, but she is far from misunderstood. Westfall knows to see through the gauze of childlike melodrama as she visually articulates the passage of Imelda’s girlhood from private knowledge to public concern.

Outfits for the pageant casting scene.

She also worked with production and costume designer Paul Jatayna to construct the visual palette and set design. Against the backdrop of a blistering summer, white linen sheets, nuns in gray habits, navy blue pleated skirts, a piña shift dress with tiny pearls stitched to it (a piece owned by Westfall’s grandmother) help evoke a midcentury, post-war Philippines, filtered through the eyes of a young Imelda, portrayed by actor Polly Cabrera.

“Our superhero art department handmade and installed the signs for the pageant.”

The film reaches the height of its exposition through a reimagining of the 1953 Miss Manila pageant. “I wanted to convey these little glimmers of evil that would slowly build up to the climax of the pageant,” Westfall explained. The final scenes were filmed in The Bantayog Center in Diliman, Quezon City, particularly in the Ambassador Alfonso T. Yuchengco Auditorium, where the choice of costume provided visual cues to an event that became the root of controversy. On the same floor of the auditorium is the Bantayog Museum standing to this day as a memorial center honoring those individuals who lived and died in defiance of the repressive regime from 1972 to 1986.

“For all of the pageant gowns, I raided my grandmother's and my mother's closets, which also house some of my great grandmother's dresses. The red sequined pageant gown belongs to my mother. It was Paul's choice—he wanted Imelda to wear the 'loudest' dress… For the others, I wanted a mix of Filipiniaña dresses and Western dresses to reflect the cultural identity crisis that was there at the time,” she shared.

“Every dress in the film belonged either to my mother, my grandmother, or my great grandmother.”

A critical retelling

“You can make the argument that a lot of it is fictionalized,” Westfall said when I asked her about which scenes were based on historical research and which ones were imagined. Using Saidiya Hartman’s process of critical fabulation as a model, she explained that to begin examining that particular period of Philippine history, “you have to use fiction or imagination to fill the gaps because the archive is inherently incomplete and unfixed.” Rather than giving such a controversial figure another platform, she hoped to show the “symbiotic relationship between fiction and archival material informing each other and getting at these bigger questions of what the power of fiction is and how we can unsettle our understanding of history and archive.”

This would not have been as effective if not for Westfall’s commitment to archival research, effecting moments that strain between fact and fiction, the fall from grace to corrupt infamy. “There’s such beautiful materiality to the process… It’s as if I have to get research done out of the way so that I can do the imaginative work, the dreaming work of writing stuff that comes from my own life, or my own experience. It’s just this first step of starting from whatever’s in the world and then being able to open up and play with that,” Westfall shared.

Film still.

Westfall explores the microscale, almost silent, moments when latent cruelty takes hold: we see a young Imelda playing with a turtle while fanning herself amidst a Leyte summer. She leaves it upside down on its back, flailing. And during the pageant, we catch her in the dressing room admiring her own reflection in the vanity. She lingers, in excess. The private and the public, along with the archival and the imagined, form unions that resonate deeper than when they remain as precise and discrete fragments, stirring you even closer toward the edges of truth.

Alex Westfall’s The Rose of Manila (2020) is on view at TarzeerPictures.com until May 20.

Images courtesy of Alex Westfall and Zea Asis, unless stated otherwise.

Zea Asis is a writer, a contributor for CNN Philippines, and author of the zine, Strange Intimacies: Essays on Dressing Up and Consumption. Tap here to buy her a coffee.