The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.

In the Ateneo Art Gallery, an exhibition memorializing the period of struggle brought by martial law quietly runs through the first-floor gallery. Entitled Ligalig: Art in a Time of Threat and Turmoil, this collection presents works by contemporary Philippine artists depicting the issues and political landscape throughout the late sixties onwards, especially after the 1972 declaration. Long-withheld from the public due to the pandemic restrictions, the exhibition is now open for visitors by appointment. Ligalig: Art in a Time of Threat and Turmoil runs from 14 Aug 2021 through 29 May 2022.

Installation views. Courtesy of Ateneo Art Gallery.

Ligalig: Art in a Time of Threat and Turmoil features several works from various artists that enunciate societal issues in each of their artwork. Selected by the late Emmanuel Torres, Ateneo Art Gallery’s founding curator from 1960 to 2002, appointed by the painter Fernando Zóbel, the pieces in this exhibition were generously donated by artists and alumni for the museum collection.

The title of the exhibit, Ligalig, is the Filipino translation of the word ‘troubled’, taken from the threatening environment in which these works were created. During this period, it may be surmised that Philippine contemporary art was cultivated as most artworks gravitated toward social realism, a few decades after World War II occurred. At this time, artists’ expressions were reflected by the political climate as people feared the military and civilians would disappear, their bodies found days later. Freedom of speech was smothered.

Ligalig, a Filipino word for “troubled,” encompasses the themes that remain relevant to this day — threats to life and freedom brought about by abuse of power, poverty, economic and social inequalities, and environmental degradation

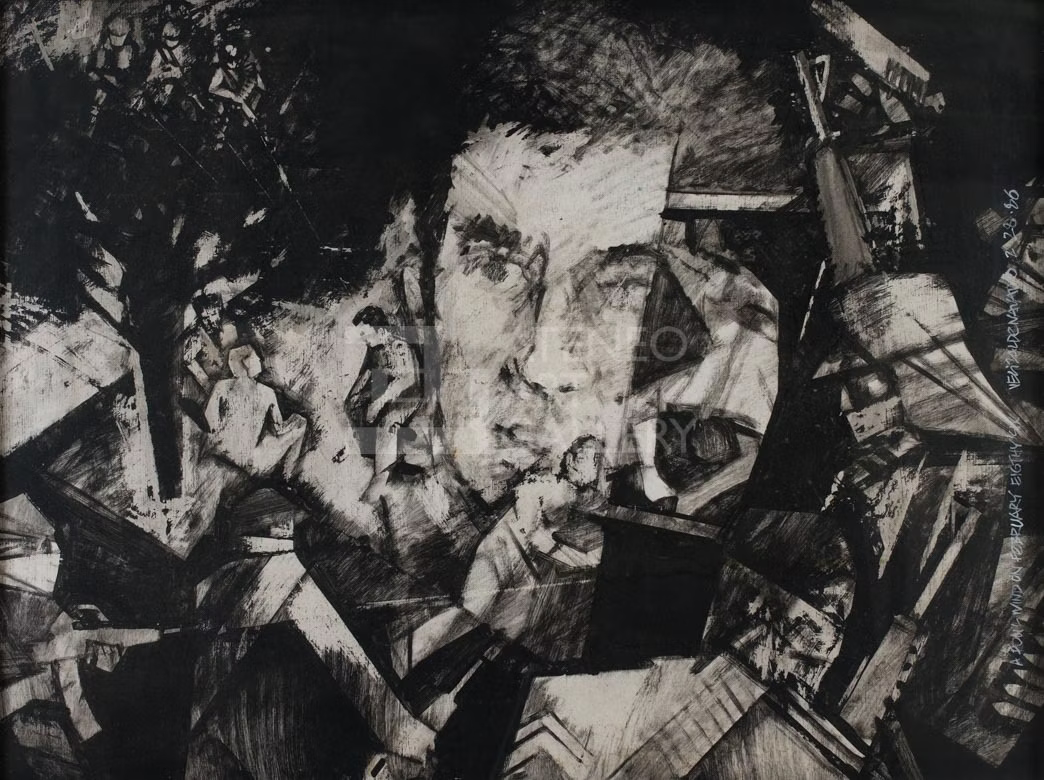

A Foul Wind in February '86, J. Elizalde Navarro. Acrylic on Board (1986). Courtesy of Ateneo Art Gallery.

One of the first artworks one encounters in the space is A Foul Wind in February ‘86 by J. Elizalde Navarro, a prolific artist who was awarded the title of National Artist in 1999. In this work, Navarro depicts a man’s face at the center of the frame, surrounded by several armed figures in his distinct cubist style. The man in the painting is Evelio Javier, a politician and the former governor of Antique who openly opposed the Marcos dictatorship in the 1980s. His assassination on February 11, 1986 was one of the catalysts leading up to the People Power Revolution, overthrowing the dictator that year.

Installation view. Courtesy of Ateneo Art Gallery.

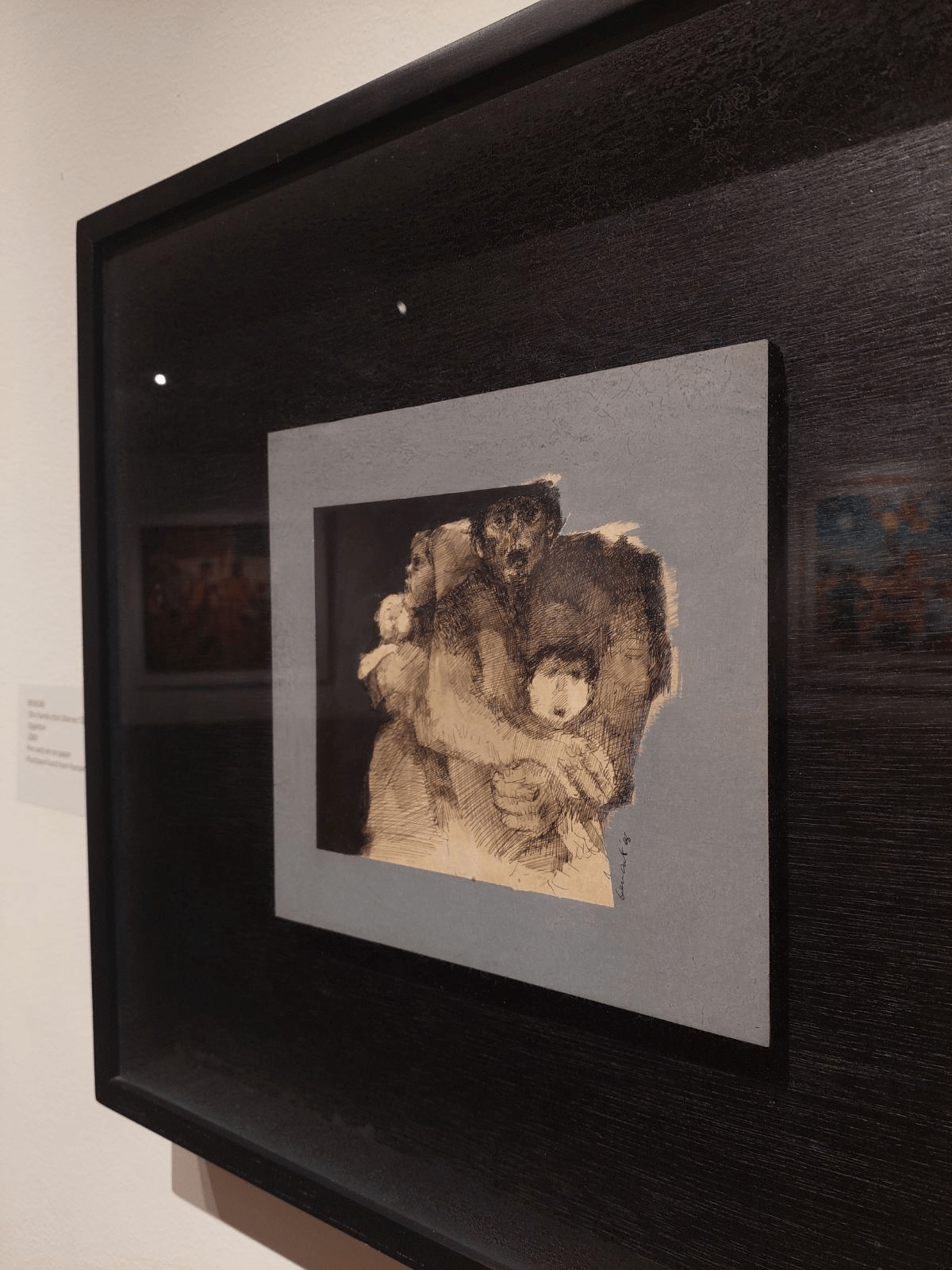

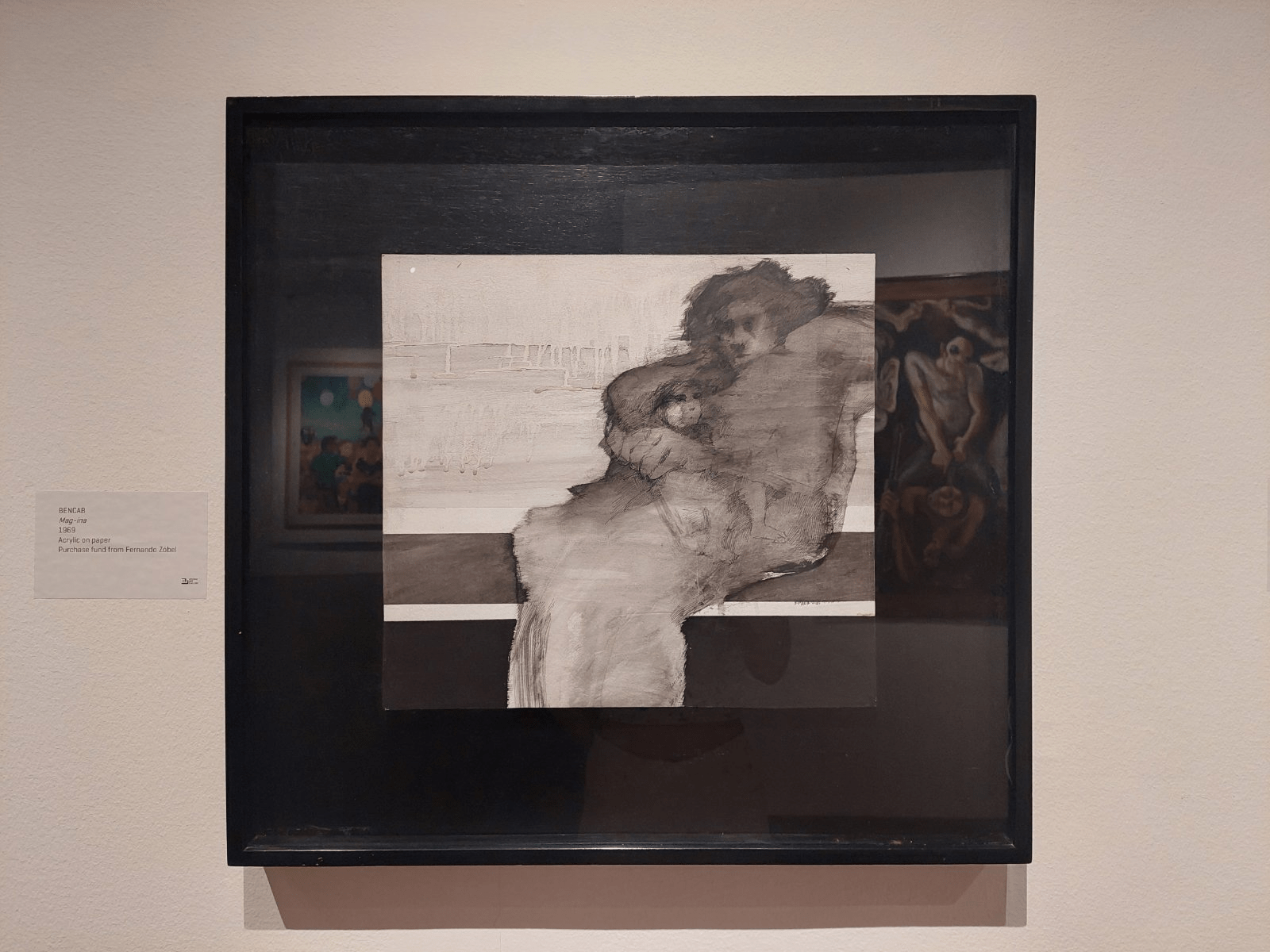

Two pieces by Benedicto Cabrera —another National Artist, commonly known by ‘BenCab’— center on familial yet haunting scenes, portraying an impoverished family of four in The Family that Starves Together Stays Together (1968) and a mother and child in Mag-ina (1969). Both works on paper were acquired by the museum’s Purchase Fund from Fernando Zóbel.

In these works, the absence of color reduce the figures to ghosts. Set against rough and sharp edges, they capture the harrowing reality of a time that spared neither the young nor the old. Painted across the faces are sunken, hollowed-out expressions — mysterious yet evocative images that appear to float, almost robbed of corporeal existence altogether.

Kinupot, Edgar Talusan Fernandez. Molded canvas over wood armature (1977). Image courtesy of the writer.

The martial law era was notorious for the many disappearances and abductions of those who spoke against the government; these people were known as the Desaparecidos. During this period, numerous human rights were violated. Some victims’ bodies were never found at the time of the military rule, as extrajudicial killings became rampant.

Kinupot by Edgar “Egai” Talusan Fernandez was created in 1977 and gifted by the artist — known for his socialist-realism paintings and involvement in political activism. Kinupot is a tribute to the victims of martial law—specifically the Desaparecidos. Known for his social-realist works, Fernandez’s paintings often depict scenes that allude to power struggles and a sense of nationalism.

In the form of a mangled cloth covering what appears as body parts, this sculpture is a tribute to those who fell victim to the disappearances and the deaths of over thousands of Filipinos. With material that is likened to fabric, this mirrors the act of covering — hiding what must not be shown and is left unknown. Through this, what is underneath the surface remains anonymous — nameless victims abandoned in the dark disappearing mysteriously, identities kept as incomprehensible as the efforts to uncover truths difficult to face.

Contemporary artists continue to be vigilant and responsive to current issues, as evidenced in works acquired in later years. Whether employing traditional or conceptual and new media modes of expression, they continue to underscore the role of art as a critique of the prevailing social and political order.

Adjacent to the aforementioned sculpture is a 2014 installation by Eric Zamuco entitled Wadapak/Dapak. Consisting of student chairs, neon, and light sequencers, the artist ‘restored’ broken armchairs from the University’s storage by completing the missing parts of each chair with shaped glass tubings and light.

Wadapak/Dapak, Eric Zamuco (2014). Images courtesy of the writer.

‘Wadapak’ was the chosen title by Zamuco — a wordplay of the often expressed English expletive to reflect Zamuco’s ‘initial shock at the display of historical amnesia.’ While this was being conceptualized, photos of the former first lady Imelda Marcos (invited as the guest of honor to a scholarship fund event) posing with scholars and admin from Ateneo de Manila University were circulated and criticized.

Dapak references a work titled The Pack (1969). Using sleds with survival kits organized to resemble a pack of dogs, artist Joseph Beuys’ work is a metaphor that looks into dealing with the guilt about Germany’s history of war. Similarly, Zamuco uses the student arm chair and light as metaphor for intellectual sustenance, highlighting that “education makes possible the process of care, orientation, restoration and salvation of a different kind.”

Wadapak/Dapak, Eric Zamuco (2014). Image courtesy of the writer.

This year, the artist included a sequence in the tubed glass that briefly fills and flashes to a bright neon pink that disappears after — an allusion to the upcoming national elections in May. This reference stands as a possibility of change; a light of hope within what exists despite attempted revisionism and the act of forgetting.

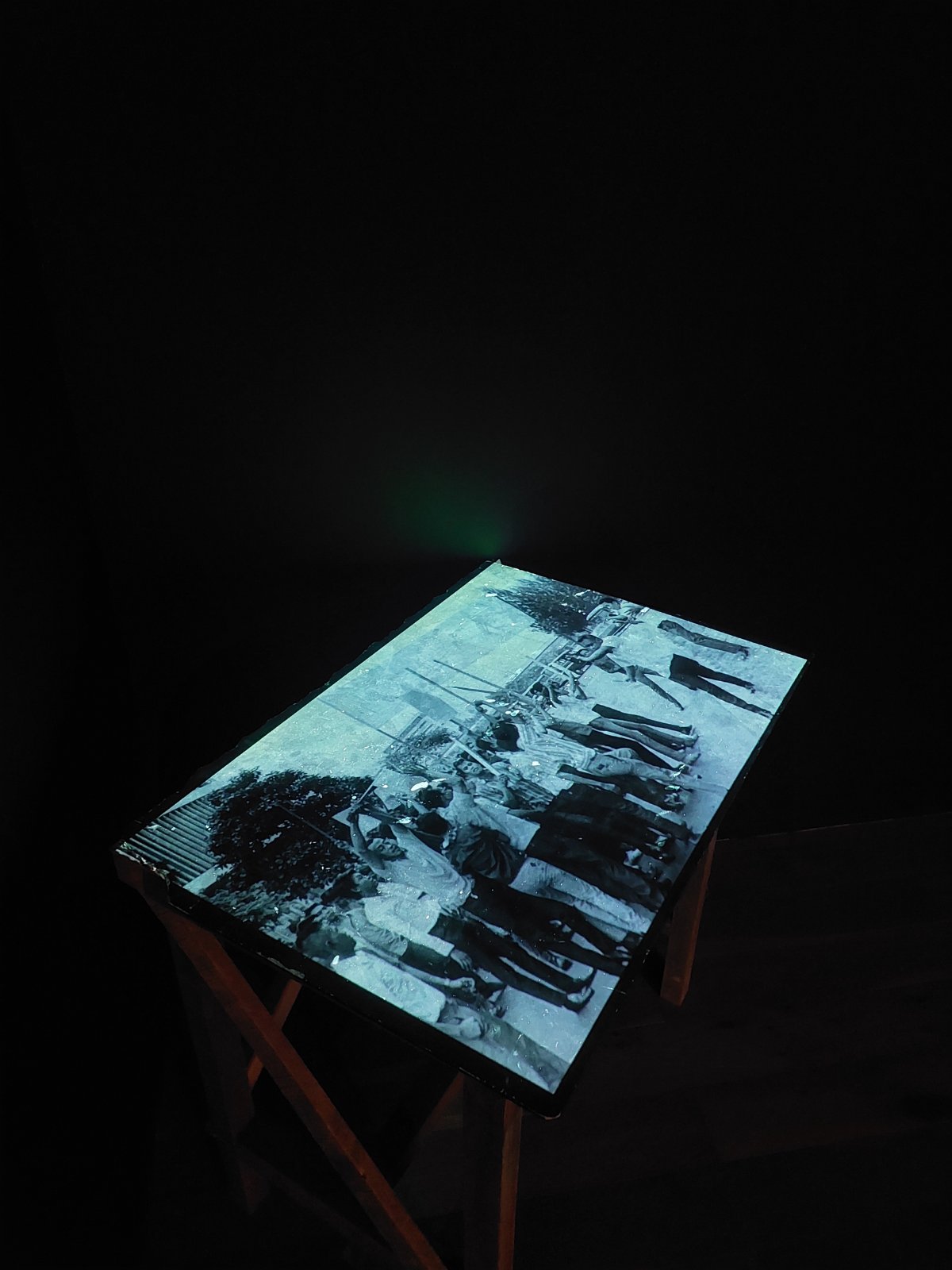

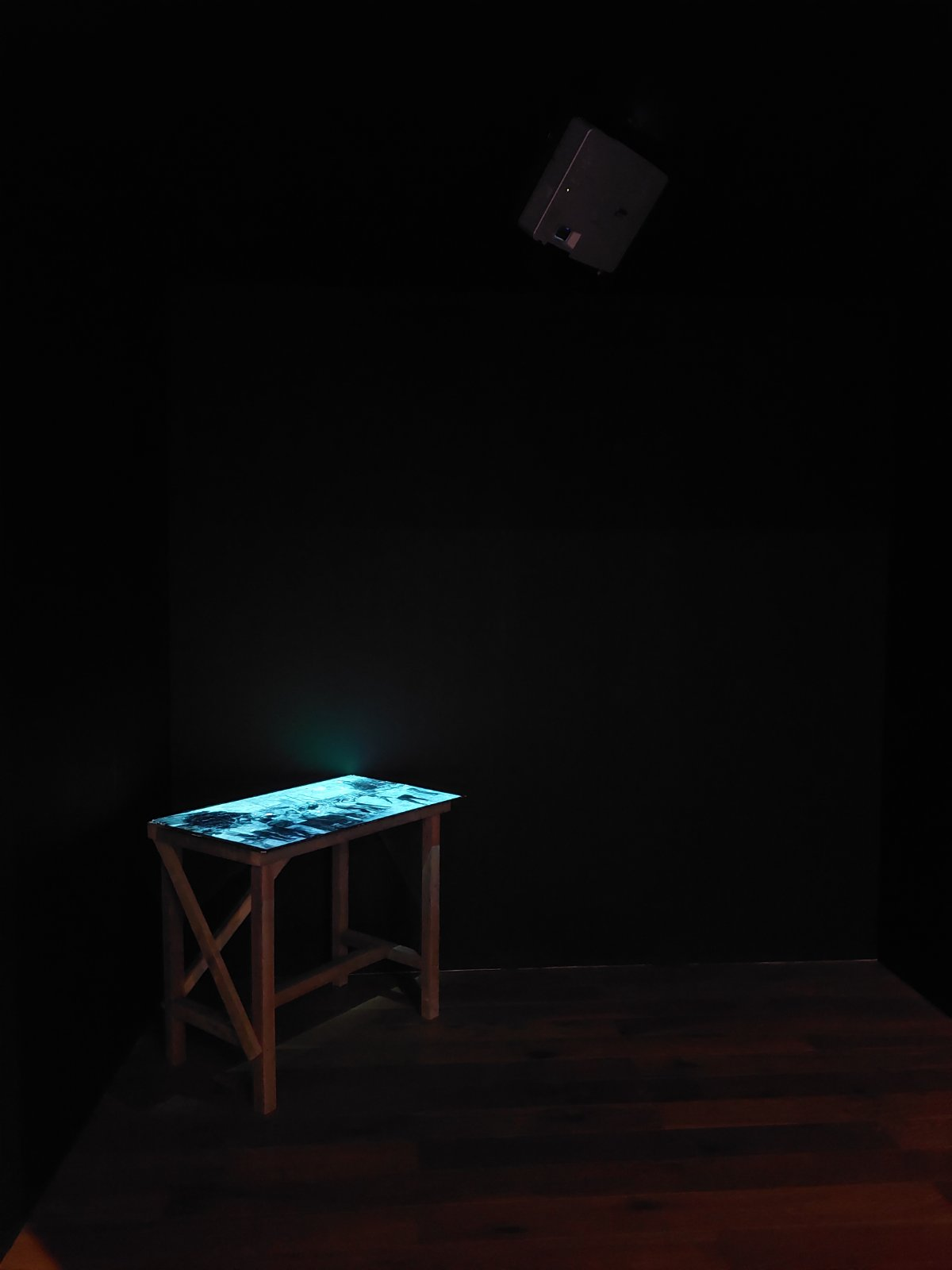

Across from Zamuco’s installation is Erased Slogans by Kiri Dalena. Stepping into a dark room, one encounters a desk at the corner showing projected images by the artist. Erased Slogans is a series of archival photographs wherein the artist digitally altered to remove words from protest signs in the early seventies. In these images, mass mobilizations of protestors in the Philippines are seen holding placards — scenes taken in the years prior to the declaration of martial law by the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos in 1972.

Here, Dalena erases the context and historical implications found in the written signs, censoring them in a way that removes what is expressed in these demonstrations. In stripping each image of words, the artist leads the viewer to contemplate the messages written on each of the placards — an alternate premonition of the restriction and limited freedom of expression once martial law was enforced from 1972 to 1986.

These works remain as significantly relevant today as they did in their time. As Filipinos await the elections, with less than three weeks before the registered population is given a chance to choose the nation’s leaders, Ligalig presents a diversity of artists, works, and practices that come together underneath a singular theme: the fear brought by injustice and corruption propagated during this dark period.

At a time of prolonged historical revisionism, the threat of erasing the atrocities and crimes of the Marcos regime is assumed by the mass spread of disinformation. In a critical stage that determines the country’s future, one must not only be vigilant but brave — as the artists’ voices resonate and continue through expression in the sign of the times.

It is unfortunate that the same issues and problems from decades ago still persist. These are made even more evident by the pandemic. One important change though is the freedom we now have to present this project without fear of any consequences or threat. It is this freedom that we need to value and to protect for future generations.

Established as the first modern art museum in the Philippines, the Ateneo Art Gallery continues to provide contextual, thematic, and thought-provoking exhibitions featuring pieces from its permanent collection and relevant contemporary shows through the years. Ligalig: Art in a Time of Threat and Turmoil runs 14 Aug 2021 through 29 May 2022 at the Mr. & Ms. Chung Te Gallery, UGF of Ateneo Art Gallery.

Also on view in the gallery is the recently opened solo exhibition entitled Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts by London-based Filipino artist Pio Abad, whose works tackle historical narratives in the Marcos dictatorship.

Schedule a visit to Ateneo Art Gallery in Areté, Ateneo de Manila University at bit.ly/VisitAAG.

Meg Genuino is a contributor to Cartellino.