The position and opinions expressed here are the author's.

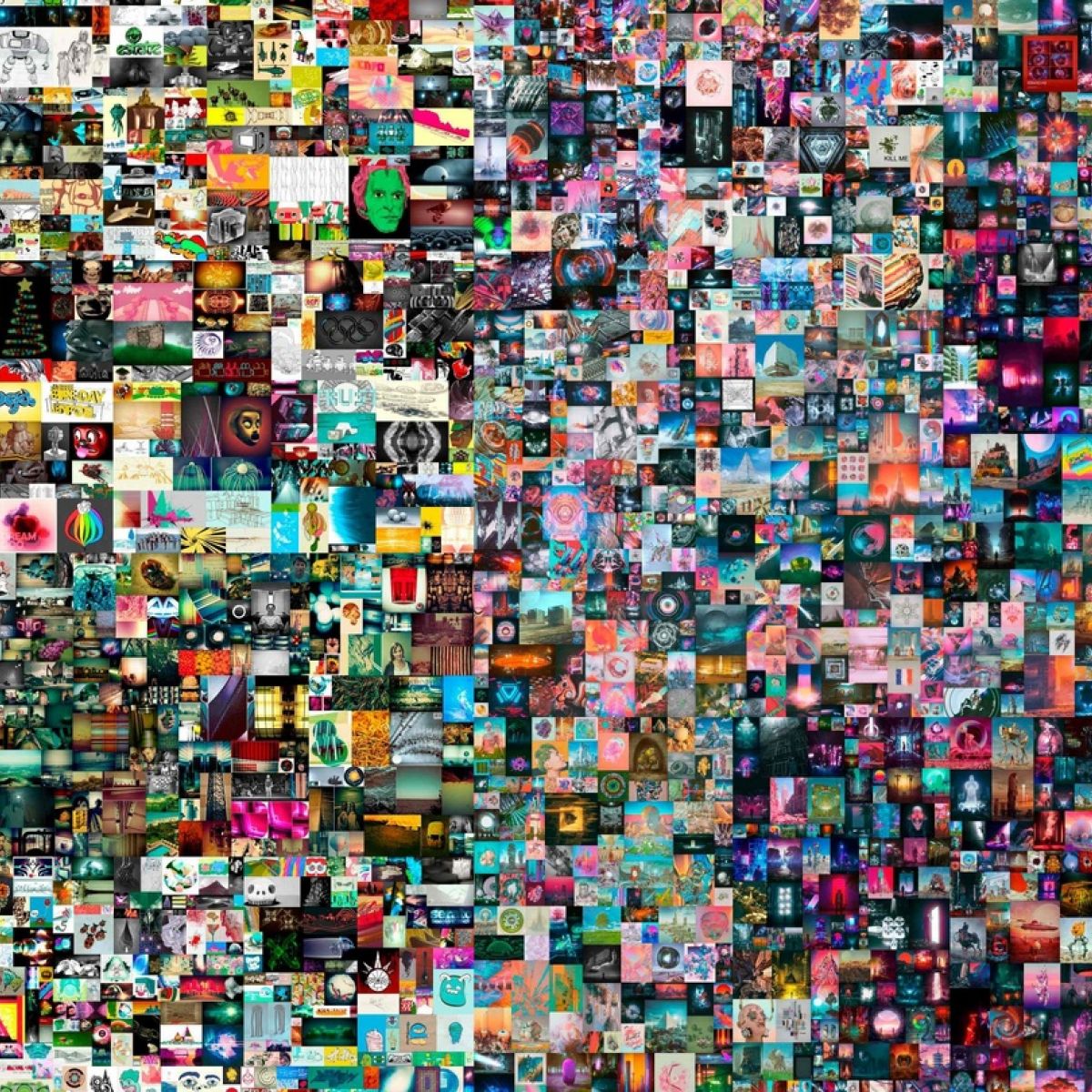

Seeing NFTs on the net, one might probably let out a sigh and mentally reject them as a legitimate form of art, deviating as it does from the accepted notion of what we commonly define as “art.” An animated flying cat almost akin to GIFs, a pixelated copy of Mona Lisa, or a collage of an infinite number of photos seem like mere digital images that readily brush aside concepts, such as “creativity” and “genius,” and thus have no inherent “value.” As we belong in a society where priority is given to painting and sculpture over other visual forms of expression, it is but natural that questions about NFT art start to bubble up and grip our minds, in particular why such an art form — despite it not being spatial-based — commands such a high price in the art market? And why, even in all its “dematerialized” form, does NFT art continue to attract a significant number of people in both global and local art scenes?

Its recent resurgence, as much as it has likely provided stimulus among art scholars, has become an impetus for this essay as the art process that informs it, though anchored in advanced technology, seems quite embedded within the field analogous to the radical art of the European avant-garde. NFT art as a response to contemporary time recalls to mind the tight-knit group of Dada artists who had a marked influence on the art discourse of the early twentieth century, and whose radicalism has laid much of the groundwork for succeeding artworks that seek to challenge the strict set of painterly rules and conventions specified by governing art institutions.

The creative anarchy prevalent in Dadaism can be largely observed in many artworks categorized as NFT art. Just as Dadaists went to extraordinary lengths to resist the formal artistic conventions being elevated by Modernism, NFT artists also have a quite peculiar affinity with artistic processes that are far divorced from the visual vocabulary embraced by artworks confined inside the white walls of traditional art galleries. For example, a digital item as banal as a tweet was converted into NFT art and got sold at a final bid of $2.9 million. Twitter co-founder and CEO Jack Dorsey owned the tweet.

This process of handpicking just any item and converting it into art runs parallel with the Dadaist practice. The best example would be Marcel Duchamp’s famous readymade, Fountain, which was practically an uninstalled urinal turned upside-down that Duchamp had selected and signed with the pseudonym ‘R.Mutt’. Very little modifications were done to the urinal before Duchamp submitted it to the exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists. Notice that in both accounts, the creator of the ordinary-object-turned-artwork expended minimal skill in the artwork, if at all. The creation of the artwork did not necessitate much artistic skill more than it necessitate the authority of the artist to confer to it the status of being “art”. NFT art, more or less, operates in the same way. However, in the context of NFT art, the authority of the artist is replaced by the authority of the blockchain platform. By making something — that is by nature copiable, paste-able, share-able, and endlessly replicable — “scarce,” the blockchain is breeding a new kind of art that obtains its value by virtue of possessing the aura of being an original work. In this context, engendering value through the medium of NFT has thus two implications that run in opposition with each other.

First, since NFT-based art means that the artwork is stored in a blockchain platform as an immutable token, it comes with a publicly visible ledger detailing its entire ownership history. Information includes the “primary” market of the artwork, such as the creator, the first collector and the sale or purchase price; as well as the record of the “secondary” market or all the subsequent changes in ownership and valuation that the NFT-based artwork has gone through over time. This is not the case with the traditional art market. Art galleries have been accused of blatantly lacking in transparency, especially when it comes to pricing, and creates this so-called veil of secrecy regarding relevant information about their art collection. Though mapping the entire transaction history of an NFT-based art can consume a considerable amount of time, it still affords people a degree of transparency that the traditional art market can give but has chosen to withhold. The publicly held data stored in the blockchain art market can never be altered by anyone, and as such makes the blockchain ecosystem an efficient platform in resolving disputes regarding ownership or damages incurred in the tokenized artwork, if there’s any.

This democratizing nature and sheer openness of the NFT art market make it appealing to most people and artists who have long been deprived of honesty by the culture of information opacity embraced by the traditional art market. However, inasmuch as NFTs promise to level the playing field for the people involved in the entire art market, it also comes with its own warnings that we should all heed. Though the blockchain platform can bestow originality to a digital item encoded in its system, and thus develop a sort of “armor” against fraudulent ownership and forgeries, this quest for originality is not for benevolent reasons as much as most of us would like to believe. The process of minting which ensures that a digital item becomes a non-fungible token or NFT correlates to the issue of authorship, which includes the notion of authority, authenticity, and originality. NFT therefore brings to light modern society’s eternal predilection with originals; and, with it, the disgust and anxiety that comes with possessing just a “copy.”

If one is observant enough, one could see that NFT manufactures scarcity by validating and securing the original copy. The aesthetic value of NFT art thus resides in its quality of engendering originality through the blockchain. Therefore, it doesn’t matter at all if the artwork is not as beautiful or painterly as the masterpieces displayed in the Louvre or any other prestigious art spaces; the defining aspect that demonstrates its value is ultimately linked to its quality of being minted in the blockchain — no more, no less.

This placing of importance on value inherent among NFTs implies a system of hierarchy, and this hierarchy that lurks behind the blockchain technology is in concert with the terrain of Modernism where binary oppositions are used to establish value. In the context of NFT art, the binary opposition involved would-be high art/low art, with the digital art converted into NFT art — plainly, art “worth minting”— and now positioned as “high art” through the originality bestowed by the blockchain technology. Suppose there is no blockchain technology. Digital art would pale in value compared to traditional arts like paintings and sculptures displayed in museums and art galleries. Blockchain technology thus aids in creating and maintaining this opposition so that NFT art would appeal to investors and artists who want to obtain profit or hedge against market crashes. Though intermediaries like art dealers can be dismissed in the whole process of selling art on the blockchain platform, the stark fact that NFT art is just another means to regulate and/or circulate money cannot be denied. Artists are once again hurled into this money-making rabbit hole where capitalists are at the bottom of. NFTs will just further reinforce the same old hierarchies and the same old power relations between artists and the art market. The same mad rush of accumulating future capital is invariably what fuels this market. Enhancing the value of an artwork through manufacturing originality just creates an aesthetic of sovereign greed that all the more elevates billionaires and inevitably loses the potential of blockchain technology as a genuine protector of artist rights.

The observation that NFT art all the more reinforces the power structures, hierarchies, and exclusivities in our society also coalesces ‘at some point’ with the notion of aesthetic exceptionalism, which many art scholars identify as the structuring logic behind any artwork. Aesthetic exceptionalism, tied to theories of artist-as-genius, realizes itself in the digital realm through NFTs. The market’s structure and value’s structure remain the same—it’s just that the transaction relocates itself in the immaterial world of the digital instead of the physical world of art galleries and other sanctioned art spaces. To understand this “relocation of meaning,” we need to go back to Walter Benjamin’s enduring insight in his influential 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” where he claimed that the development and eventual proliferation of new media and technology like film, lithography, photography, and video is to the advantage of the proletariats or the masses.

Through mechanical (and now digital) reproduction, new technology fractures the aura of the object, which diminishes its value and changes power relations in a given society. The “aura” is this quality of being unique that derives itself from the fact that an object is made by the hands of an artist or has undergone a ritual, either religious or secular, that occurs at a given space and time. By eroding the aura of the object through technologies capable of infinite replicability, the ownership of the means of production changes and strips the artwork of its “uniqueness” and, consequently, its monetary value. The NFT medium then is the means through which contemporary society tries to resurrect “aura” as it is through the aura that they can maintain bourgeois and fascist conditions that sustain a capitalist society. The digital may have held the promise of liberty and equality — noble ideals espoused by communism — but originality through NFTs is devised to pervert and sabotage the communism of the copy and surrender us back to the fascism of the original, to which modern society tried to escape from (though in vain).

With that, it seems quite clear now that we are trudging on a path where art is more and more reduced to a financial instrument. NFTs may be vicious and politically troubling in all their crypto glory. Still, as a scholar of art, I am under the impression that this topic would pave the way to intellectual exchanges and dialectics that can, if done right, free art from the claws of fascism. As wise men say, it is always darkest before the dawn.