Zine fairs are warm, vibrant spaces where eclectic individuals celebrate intimate, messy art. They are safe spaces for creatives and strangers to meet and share their appreciation for the different forms zines may take. Zines are limited-edition, self-published books, often photocopied and distributed locally; being uncensored, they have the potential to be raw and unrestrained. As a format, zines began as a space to talk passionately about popular culture but soon developed into a way to spread information without interference. Some zinesters today use it as a form of therapy, others as resistance. As a zinester myself, I frequently attended zine fairs to sell and trade. Before closing, I would make a trip around the convention center or warehouse and look for zines to buy. Then, upon arriving home, I lay my zine haul before me like a sloppy buffet, and I go on eating greedily. I flip through pages and skim through lines. The zines I enjoy are those that come across as a little too personal, like they were made with embarrassing affection. I also like zines that are just playful, the ones that don’t mean much. The kind of art that amuses me is art that says a lot but doesn’t really mean anything profound.

It is just as it is. Though there are many aesthetically pleasing and professionally created zines, most zinesters often work with what they have. So, one might expect grammatical errors, clumsy prose, and printing mistakes. This freedom is what draws many artists and writers to the form, allowing them to express themselves fully. With that, there is no question that zines could be bad, inappropriate, or even selfish as art. It is more important to see why the zines were made, and how they make you feel. When reading zines, I rarely analyze what I see, as I find this distorts my imagination.

The lockdown inspired me to revisit my collection of zines from before the pandemic. Looking through my collection reminded me of the warmth of physical zine fairs. I have chosen a few works that have resonated with me, zines I admire for their intimacy and honesty. The zines presented here are samples of the messy range of sexuality and dissent, two themes well suited to the zine format. The uncensored, barely edited nature of zines creates a space for honesty, and so reading them can sometimes feel like you’re intruding. The first three zines presented here read like excerpts from private diaries: hasty, tender, and mildly embarrassing. They celebrate the intimate and distant aspects of sex, its intoxicating allure and lingering nausea. These three poets ramble, unafraid to be immoral and sorrowful. In “Good morning / Goodbye”, Belle Cabal sleepily recounts fragments of half-forgotten encounters with forgettable people. Frank Tamayo’s “This Fine Mess We Have Made” contains vague homoerotic poetry accompanied by hazy, suggestive photographs. Rayji de Guia’s “What could have been water” is a suite of mystical, sapphic poetry dedicated to a passionate and consuming love. In these three zines, the poets undress and reveal their flaws and perfumed desires. Looking at them can be either awkward or inviting.

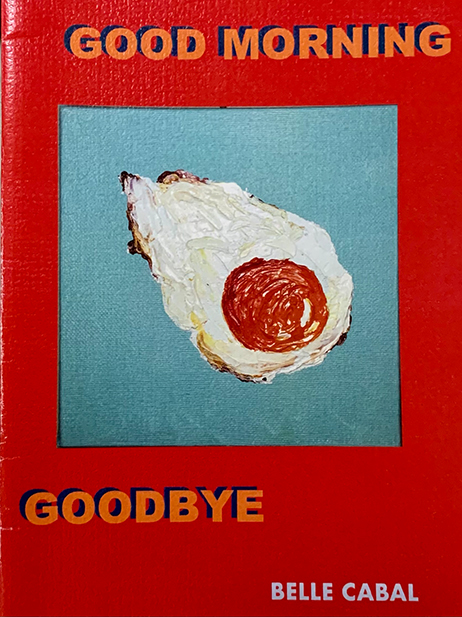

“Good Morning / Goodbye” by Belle Cabal

The persona starts by complaining that they’re tired of the emotional foreplay that precedes vulnerability, so they just spread their legs. There is a kind of tiredness and detachment here. The first poem, “Welcome”, is a flashing sign pointing directly at a womb-like entrance. It is a resigned acceptance of the persona’s dizzying state of being, and a statement that seems to say, “Take me, but take me as I am”. They thank an imaginary award-giving body and say:

I am pleased to announce that I have been nominated

For early onset Alzheimer’s disease. It is with great gratitude that

my years of work with bipolar disorder has yielded fruits—

plums in freezers, a dish of peaches in Russia,

then the figs with their secrets. And I have held this secret for so long

except when making love and men open me up

To be greeted by carcasses of wasps that only ’til that night

Have been thick and buzzing with their poison and I say

They are safe and they are dead

This clunky excerpt colors the rest of the zine. The following poems talk about abandonment: unfaithful men stirring the oedipal memory of an absent father. This is called out directly in a poem entitled, “Your absent father would be proud”. History is confirmed over and over again, as strangers fuck in vacant parking lots and seedy motels, just as their parents did. In “Park and fill”, Cabal uses the double entendre to imply sex at a gas station. In “Limited to scenes from Paradise”, the persona romanticizes these trashy scenes, as in this awkward, panting excerpt:

where bodies touch, the feeling, all at once

a violation and yet an arrival—

but only momentarily. It closes the split

second of coming; hard

to believe it’s possible to witness such

a thing in the back of a car,

or the moment “NO” glows before the “VACANCY”

sign, maybe even in the morning,

before he leaves for another woman. We cannot

regret what we haven’t tasted.

This attitude is echoed throughout the zine and is related to a hazy mental state. From the first poem, the persona has made it clear that they’re mentally ill. They never blame their behavior on their mental illness, but they acknowledge its impact. Their manic episodes motivate reckless, impulsive action; their depressive episodes inspire reflection. In “Look, taste, hold on”, the persona realizes that they are not suited for domestic life because of the muck that is their life. They gain this realization after accidentally burning soup.

What attracted me to this zine was shallow: It is bright red, there is a silly painting of an egg on the cover. But it is a zine about a rabid lust and mental illness. I understand it deeply, as I am intimately knowledgeable of the reckless, impulsive dangers and debilitating lows of bipolar disorder. This zine is the residual sickness of a bad decision. After reading it, one might sense the faint smell of unwashed sheets and the stickiness of a stranger’s saliva—proof of a glorious night worth forgetting. The poems are poetically bizarre, sure; it is as though the persona is talking quickly and out of breath. But you know the breathless speaker is trying to say something and that this took a lot of courage for them to say. As an afterword, Cabal says, “These poems saw the light of day because of my dear friends who laughed with me through this year’s happy (and I use this in poor hindsight after months of grueling therapy) mistakes.”

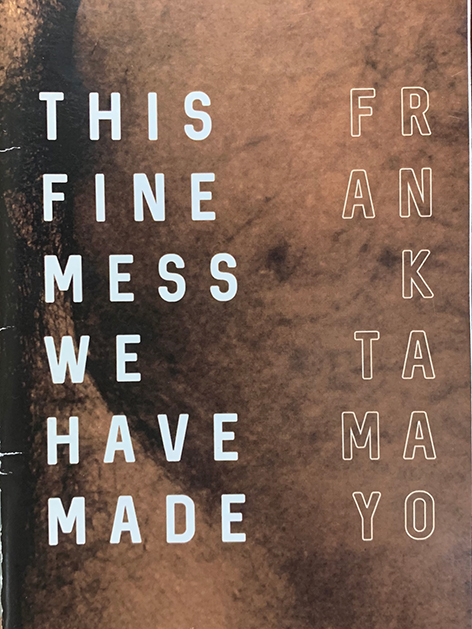

“This Fine Mess We Have Made” by Frank Tamayo

Tamayo’s zine might come across as simple and, to a point, somewhat embarrassing. But that, to me, is its charm. I like it because it is out of place and earnest with its vulgarity. The speaker begins at the end of the night. Walking into the fluorescent light of a convenience store, they awaken to the taste of beer and spit and hints on mild self-disgust. There is no self-reflection, only the emptiness of a body well-spent. This is one of many nights like this. Thus, he sighs in “7-11”:

3 AM: the 9 PM soul arrives

after wandering through

men’s houses.

The clerk pays

no attention to the door’s

chime

The stranger cruises,

points to a cheap meal

among the selection;

only so much meat

can fill the biggest siopao,

fit the gaping mouth.

He swallows, not bothering

to savor. The stranger

leaves for the night again; empty

stomachs retain hunger.

Next time the store announces

his arrival, emptiness greets

his hair messy, eyes bored

over evidence of a long night,

Red Horse and spit breath,

clothes stained, and his recent limp

with another cheap meal.

It is almost as though someone was telling a story after the tipsiness had worn off, and it is replaced by a gentle tiredness. What follows are blunt poems that feel like they were sleepily written by a young lover, like the speaker just wanted to recapture the feeling of being in the folds of their beloved, capturing their stench. In “SAND”, the persona wants to penetrate all their lover’s spaces, almost to the point of irritation, like grains of sand. In this uncomfortable excerpt, the persona has entered; it is the memory of a rough, raw night:

Feel me, restless on your thighs,

the creases of the body

and the fabric friction between.

Dust me off, I stay,

even now; a phantom sensation

on your legs, chafing

still, the hard

to reach places.

The itch etched into muscle

memories (how I can be so rough).

When you leave, you still want

to come back—yearning

the unease:

riding up your gaps,

burrowing into the heat

of my hold.

The grainy images beside each poem are bedsheets and phallic silhouettes. At first glance, the images seem harmless, but stare at them long enough and you will see that they are, in fact, pornographic. They only indirectly complement the poems; the themes are not the same. Beside a poem about a fantasy about a waiter, the image is a set of blurry shapes that one might eventually recognize as the hanging head of a penis. Perhaps these strange images are what is always on the speaker’s mind.

“What could have been water” by Rayji de Guia

Upon opening de Guia’s “What could have been water”, one smells the scent of flowers, summer, and sangria. The persona speaks of heavenly elegance—they make comparisons between the lover and the divine femme. The poems are light, bright, and sweet; there is laughter and pleasant merry-making. It is a return to nature and to what is most natural. In “Las Chicas”, the speaker laughs in a mild afternoon and breathes an earthly amour:

[...] A palm touches

my name. Smooth as petal,

you say. Braids fall

to my shoulder, strands thrill

bare skin. Fingers

intertwine. Remember

the mangoes you ate for merienda,

the nectar that lingers from

your lips? Now in my tongue.

As the sun sets, whispers

become prayers and prayers

obscene.

While Cabal’s poetry zine is best read in neon motels during a rainy twilight, and Tamayo’s poems evoke the tenderness of midnight, de Guia’s zine awakens to a fine morning. Gossamer curtains and pastel skirts sway in the fragrant warm breeze as fingers touch. Fair shoulders and slender necks invite lips to begin worship. These women make mythology: they are muses, nymphs, goddesses. The reader who enters romance seeking only its charm and its delight will find both in this zine. In “Intoxicated”, the lover laughs, and their laughter scatters and shines, and this colors an intimate, tipsy night. The lover is a goddess, and the chalice is filled with the blood of the lamb. She sings:

Goddess, permit me the kiss

of red wine

from the rim of the glass, is this the blur

of your lips, redder, longing

to be taken

by someone? Give me

a drink; the thought shrinks as soon

as I drink wine like water. The chalice

shared between us spills through our laughter

This theme persists throughout the zine: the persona is alcohol-inspired, divinely blessed, and blazing with a true, ecstatic love. Nothing could be more seductive than a devout lover.

Now, the great thing about zines is that they are easy to make and easy to distribute. Zinesters use what they have—they can pick up any paper, any pen, and begin to create. Afterward, the work is handed around like pamphlets. That makes it ideal for people or communities who have something to say yet are often censored or ignored. Local artists like Makò Micropress use zines as a form of dissent, amplifying vulnerable communities’ voices and promoting various advocacies. They speak clearly and outline their actionable plans.

On the other hand, there are those who test the limits and openly ridicule those in power, such as the next two works. There are no plans, just contempt. They no longer seem to care about being polite, instead choosing aggressive, humorous irreverence. There is real anger in their twisted humor. To be clear, I respect zine collectives who are sure about their advocacies. They are mature artists seeking to make real change. Zines, to them, seem to be a tool for the uncensored dissemination of information and a way to raise political consciousness. But sometimes, I just want to snicker like a child and be angry yet not take it all too seriously. I want to throw a tantrum. The level-headed activism comes after I’ve released that tension. That is why I like Marguerite Alcazaren de Leon’s “DDS Limericks!” and Chemical Comics’ “Adventures of Extrajudicial Man”. These two zines read like they don’t care about doing anything substantial and sustainable—not right now, at least. That’s not because they don’t care—in fact, they care enough that they are affected. They’re making jokes, subverting through mockery, ridiculing those in power. They’re throwing a massive, immature, amusing tantrum. These zines are unpolished, unedited, and foaming at the mouth. They are unprocessed thoughts, hastily published out of spite.

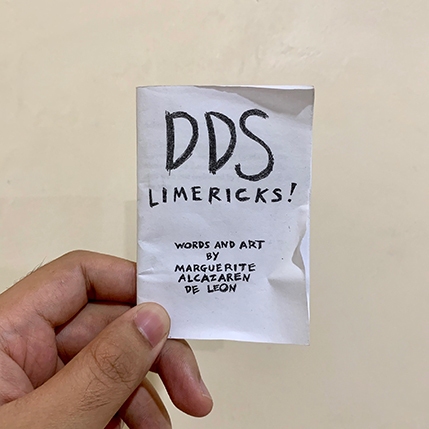

“DDS Limericks!” by Marguerite Alcarazen de Leon

In this zine, De Leon boldly presents scathing, accusatory rhymes about political figures. They insist that this was simply a personal creative exercise and has nothing to do with their employer in any way. In this zine, there are references to hate groups and hazing. There are comparisons to reptiles and direct callouts to entire political families. There are prayers for failure and jail time. Publishing the poems here would be dangerous, as they are direct and, to the right people, extremely offensive. I suggest finding a copy so that you too could enjoy the wit, but be careful in showing it around. Although the references might be a little dated (this was released a few years ago), they are, to anyone paying attention, still relevant. This is because not much has changed since the zine was released: the same old issues persist today.

De Leon’s zine might be the most incendiary zine I have. While zines of practical activism seek to hold people in power accountable, this zine has already condemned them as disgusting, sinister, and murderous. It is almost libelous, if not for the fact that one could browse through news archives and find that each poem holds some truth. The intent of this zine—as it seems to me—is to represent the feeling of standing bare naked in front of the palace and squatting to shit by the gate.

“Adventures of Extrajudicial Man” by Chemical Comics

When a large phallic robot attacks Davaopolis, the Selfie Senator alerts the Extrajudicial Man. Amid the rescue, the Extrajudicial Man and Selfie Senator take a break and enter the men’s room to have sex. The expectant citizens wait outside their cubicle, whispering amongst themselves, realizing that they are doomed. In the story, the robot, controlled by human rights organizations, sits and does nothing—they stand there, but they don’t get to do anything. So, in the end, they just leave. The story makes it more ridiculous: since the main characters refuse to confront them, the organizations just call it a victory and go out for lunch. As an afterword, Chemical Comics says that “all I see [is] this, a plain lined art story of fools running around in everyday costumes, living their own lies and ironies.” They claim to have written something apolitical and that “somehow the game of power seems just another comedy for me to draw, illustrate, and laugh [at], maybe.”

This just sounds like the artist is washing their hands. They don’t want to get into trouble for their work, even though the work is direct in its obscenity. Of course, the piece is political. The actions of the main characters show a kind of absurd unprofessionalism, a direct call out. Instead of doing something about the present crisis, they are kissing each other’s asses. There is also that comment on human rights organizations, which feels like the artist has lost hope that they could actually create change—and this isn’t because they are ineffective or disorganized. It’s because those in power won’t properly engage with them.

I would read this zine as though I had discovered the idle doodles of a lazy student. They’re only half-listening; their mind is elsewhere. They don’t care: after class, they’ll go on living their life. They mean nothing by it; they were just playing with ideas and stuff they heard from the news. I don’t think they even understand the context. Something might be said about the early cyberpunk art of Chemical Comics, which today has developed into something more distinct and in-your-face. Here, the drawings are still messy, the narrative flimsy. Then again, that is the point. When I asked whether I could write about this zine, Chemical Comics just said, “That piece of shit has been in the gutter for a long time.”