Since 2016, Jean Karl Gaverza’s Philippine Spirits has been bringing the bygone tales of the Tikbalang, Aswang, and more folkloric creatures back into the imagination of modern audiences. Inherent in his work is a desire to counter hegemonic practices in favor of cultural preservation and propagation. As a linguist, championing the many indigenous languages of the country is one of his main advocacies. As a scholar, studying and preserving the multitude of Philippine mythologies is one of his major passions. And as a writer, combining these and telling stories is, quite simply put, something he really enjoys doing. All this work would eventually bear the fruit of Philippine Spirits.

As it is, resources on Philippine myths and folklore are hard to come by. The recent success of Trese on Netflix has sparked interest among viewers, and yet Philippine mythology as a whole still remains underrepresented and overlooked. Thus, he value of cultural safeguards like Gaverza’s, much less one so accessible and comprehensive, cannot be understated. Philippine Spirits is a virtual platform where writing, research, and art meet to narrate the stories of the many mythologies native to the Philippines. Since its inception, it has served as a virtual database of over 2,000 folkloric creatures and deities, all of which are free to read on its website and socials.

Gaverza studied linguistics at the University of the Philippines Diliman, and it was there his interest in local folklore began. His undergraduate thesis titled “The Myths of the Philippines” (2014) extensively catalogs different myths and motifs, sorting them by ethnolinguistic group, cosmogony, and belief systems. He was also interested in exploring the lexical diversity of single terms like “aswang,” and mapping them out accordingly to its many associations across different communities. Paying it forward from his own sources, he has since made his thesis available for public viewing on Academia, where it has become a valuable resource among those also studying in the field.

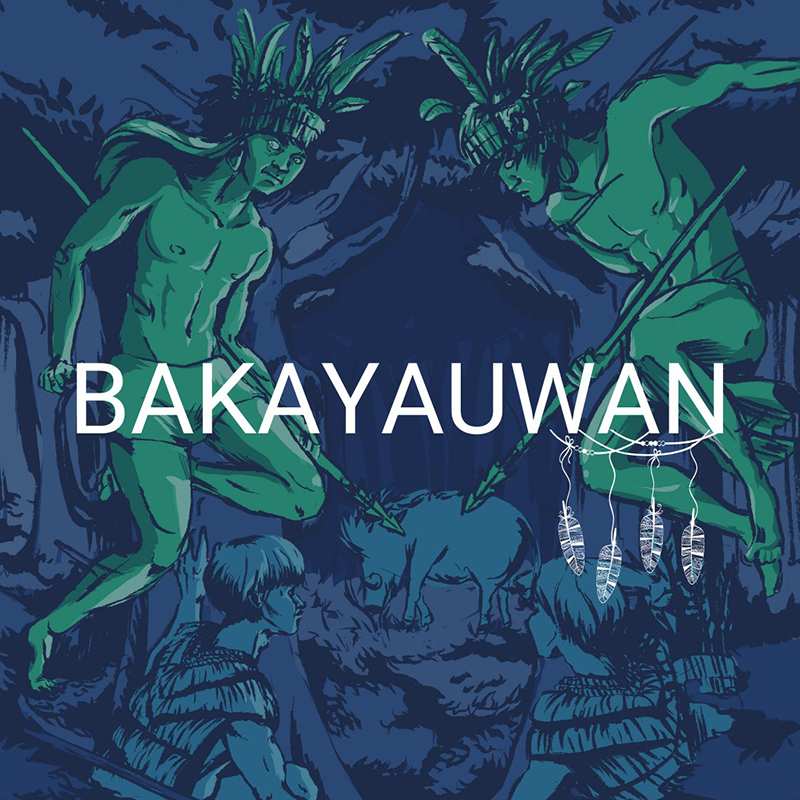

Philippine mythology and folklore encompasses a wide spectrum of creatures, deities, and superstitions ripe for storytelling. It was the enigmatic character and intrinsic elements of horror in many folk tales that drew Gaverza to the idea of retelling these stories.

On telling the stories of creatures from folklore, Gaverza says, “Growing up, ‘show, don’t tell’ was always ingrained in me. There were already all these websites that described the mythical creatures as they are, but there aren’t any that actively use them…”

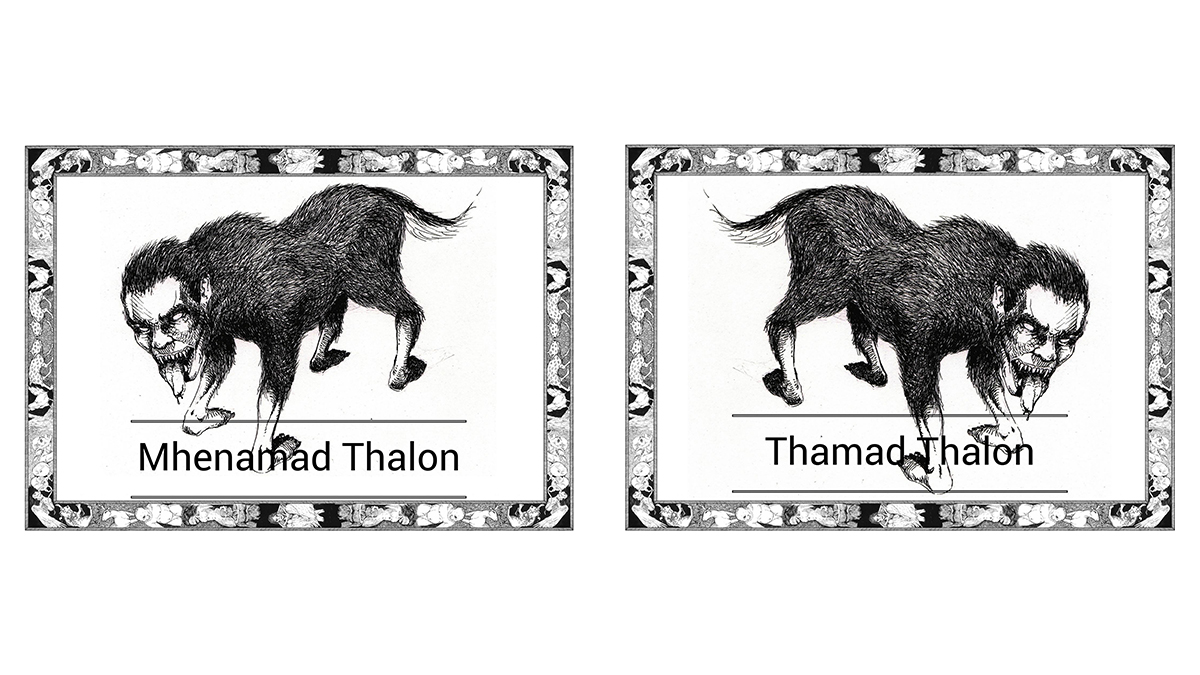

While studying the numeric system of the Southern Subanon language, he came across the myths of the dog-like creatures, the Mhenamad Thalon and Thamad Thalon. It was there his interest peaked and he saw a medium for jogging the imagination of writers and readers alike in the haunting way that only Philippine myths could. The approach of Philippine Spirits is different from that of a regular mythological compilation. Gaverza takes his research findings on each creature and uses them to weave his own fictional narratives around them, many of which make use of its roots in horror.

“Some myths and legends and folklore do have a social component to it. A lot of the time, it’s so that they can protect the most vulnerable in society… Most of the monsters target pregnant women and children. So it’s also a way to force them to stay inside or they’ll get eaten by an aswang.”

Philippine mythology lends itself well to the horror genre because of the didactic and moral aspects at its core.

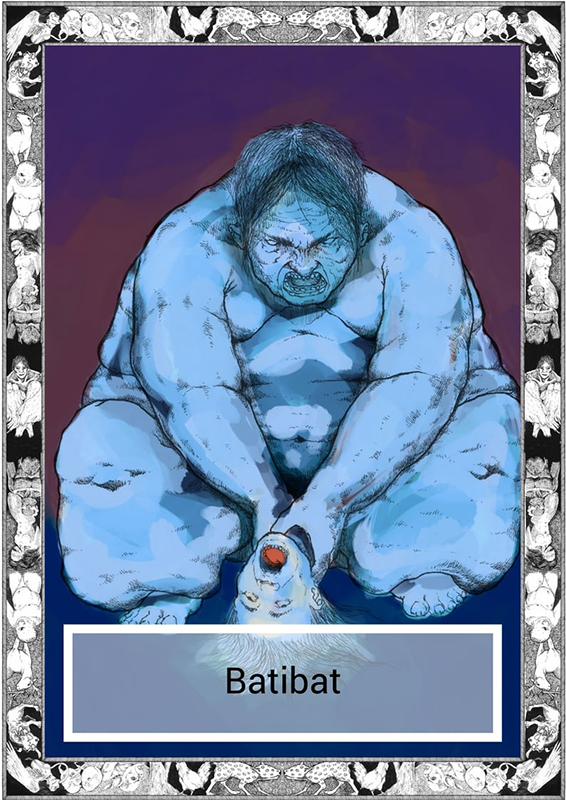

“It’s also to protect nature. A lot of the creatures live in trees, like the Batibat, for example. They live in trees, and if they’re cut down, the Batibat will curse the one who cut down her home and haunt them for the rest of their lives.”

Behind each story is a painstaking amount of research. To compile his database for Philippine Spirits, he had to hunt down the works of several prominent scholars. The texts of Damiana Eugenio, F. Landa Jocano, and Maximo Ramos are among the most highly recommended sources to consult on the matter (and sure enough, the most difficult to find). Gaverza also did fieldwork, traveling to different communities around the country and interviewing people on their knowledge on local myths to create a compendium of information that authentically reflects the cultures and experiences of people who have grown up and lived with these tales. Additionally, as of two years ago, Gaverza began getting volunteers to translate his stories into their respective local languages in order to highlight the importance of representing different ethnolinguistic backgrounds.

All that work speaks to just how many hurdles one must leap through to gain such a significant amount of information on one of the country’s most abundant cultural resources. Add to this the fact that Gaverza had to research not one, but multiple different mythologies.

“There are many mythologies in the Philippines, and you can’t pinpoint a single Filipino mythology from them. So it’s like you have the mythology of the Cordilleras, which is different from the mythology of Panay, which is different from the mythologies of the Tagalogs and the Kapampangan. It’s a lot to take in.”

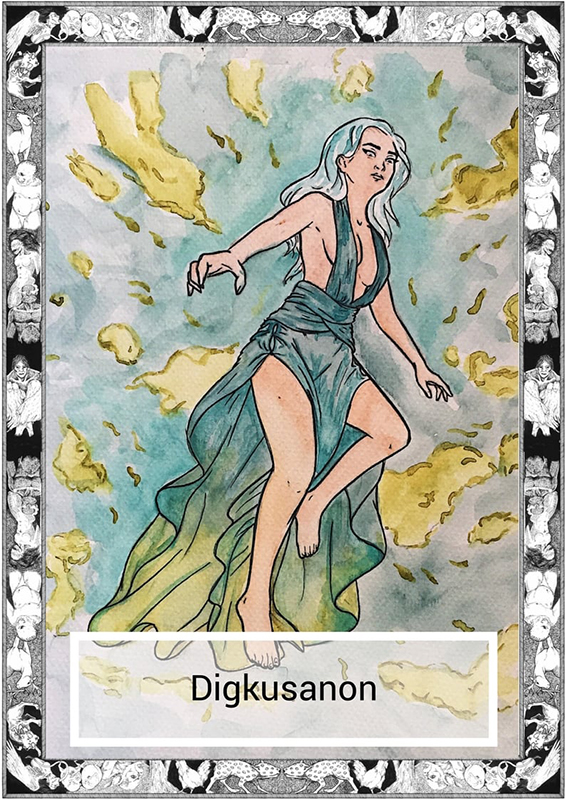

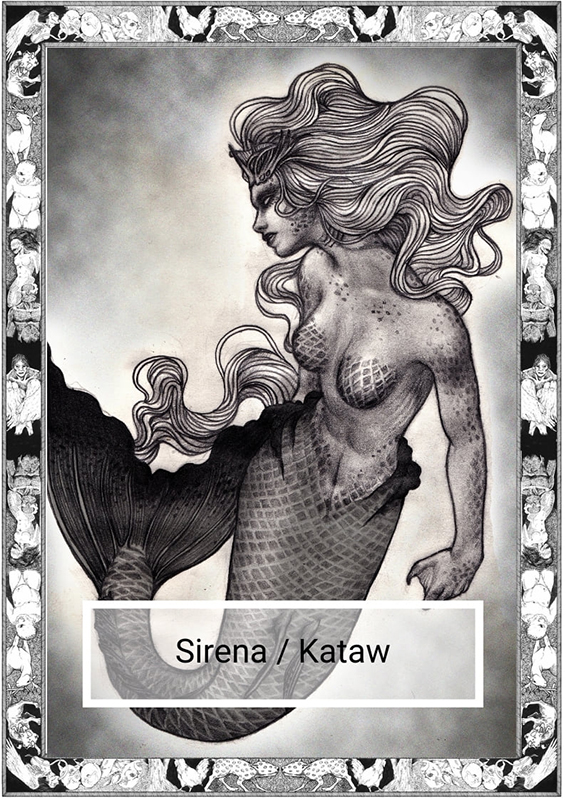

So then perhaps more than expanded storytelling, Gaverza is also helping to democratize the idea of myth-making. The short story format together with the artworks of many illustrators, serve as almost bite-sized summaries of myths that invite the viewer to take a more active role in perpetuating and shaping these narratives themselves, whether by spinning their own modernized takes or simply feeding their interest in local folklore.

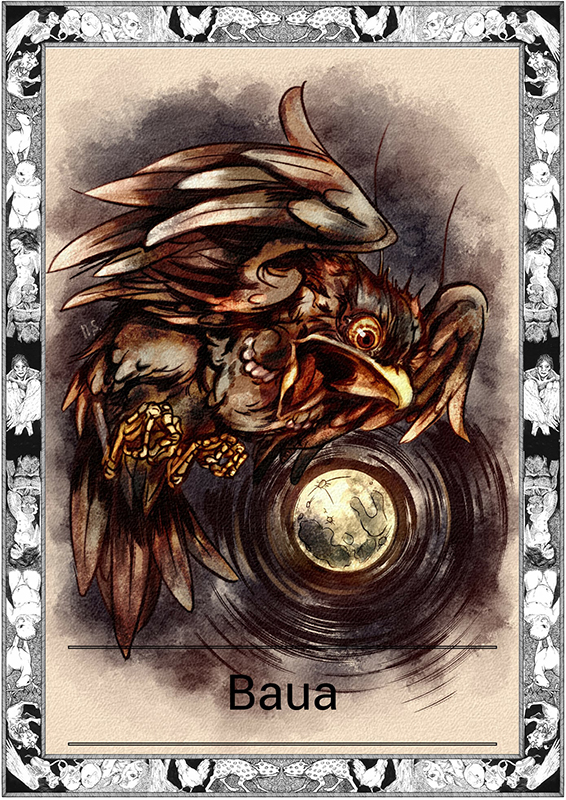

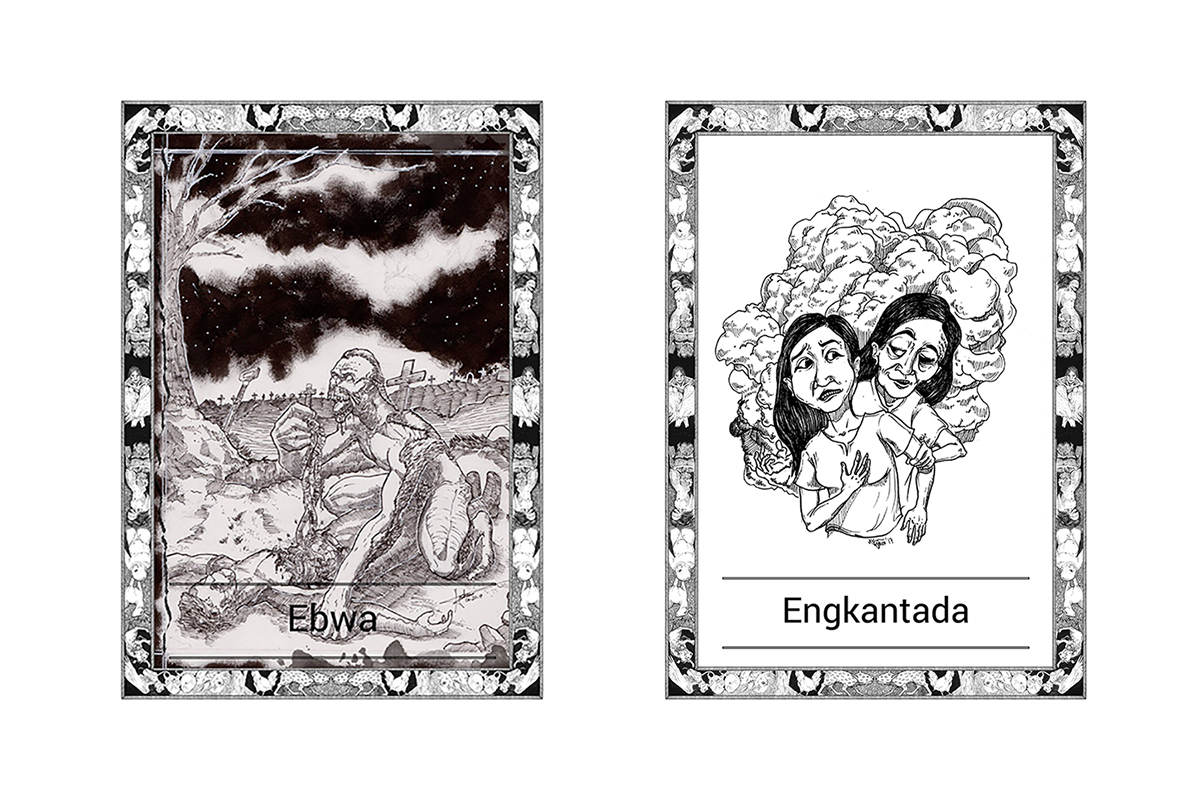

The artist, too, becomes a modern myth-maker. Some of Gaverza’s collaborators include Leandro Geniston, Catherine Chiu, Laura Katigbak, Julius Advincula, and many more. Each artist brings their own unique style to each story, using modernized visuals and mediums to describe even the most obscure creatures.

“I try to weave the illustrations in because they’re interesting. It’s hard for people to visualize something they’ve never seen before, so the artists’ interpretations are there to help them along.”

The short story and illustration format made the collections of stories from Philippine Spirits fitting for another democratized medium: the zine. Gaverza first learned zine-making from the independent publishing hub Kwago. And while he initially set out to publish a book on all his research, through zines, he found a publishing method that was easy to produce, and yet again, readily available and accessible. Philippine Spirits has since released two zine volumes: Halimaween and Mythica Obscura.

And yet with such a strong foundation laid by the likes of Philippine Spirits through a comprehensive information database, a collaborative artistic approach, and easily accessible sources, Western mythologies still hold the dominant grip on pop culture. The word “mythology” itself seems to conjure images of Greek gods rather than the pantheon of creatures from the Cebuano or Waray.

“There’s just so much content about Western mythology that you have. You have movies, TV shows, a ton of books. And Philippine mythology doesn’t have that much widespread reach.”

If there’s anything the popularity of Trese has shown, it’s that there is indeed a hunger for more Philippine myths. Following the show’s release, article upon article went viral online, leading viewers to more stories and sources on Philippine folklore (one of which was an article by Gaverza himself discussing Trese and actual mythology).

For Gaverza, there is more at stake in preserving local folklore than keeping these stories alive.

“Folklore is culture, and different cultures have different ways of looking at the world. If you don’t pass it on, that part of the world will be lost forever. It fosters appreciation of where you are and where you come from. The more you appreciate the culture… the more that you appreciate yourself, and you see that you are part of a bigger tapestry than just being an individual.”

Passing from ancestral oral traditions, to academic texts, to modern retellings, the narrative landscape of Philippine myths and legends are constantly evolving, as are our relationships to them. It’s within such a growing tapestry that initiatives like Philippine Spirits are drawing attention to the fact that there is still much magic, horror, and awe to be found not far from home.

Images from the Philippine Spirits Facebook. Cover image by the author.

Read more stories from Philippine Spirits.

Mara Fabella is an artist, writer, and occasional fitness junkie. Tap the button below to buy her a coffee.