Just inches higher from the center floor of Regina Reyes’s ongoing solo exhibition, ‘No One’s Rushing on a Sunday’, is a makeshift bed. Atop its wooden frame is a rumpled fabric sheet and pillow; plaster cast, what seems preserved are the impressions of the tosses and turns from the night before. In the time of a pandemic, when “better sleep” has become something of a sales pitch for working better, the prevailing sense is just how tenuous high-octane workaday life has made of rest.

The concept for the show came across to Regina as she woke up one Sunday morning, remembering she had to work that day for a sideline. “It was around the time I was having breakfast I realized, that even for a brief moment, I could breathe,” she shares. Typically, the best that Sundays have to offer is some leeway in the partitioning — time to reflect, hours to sleep in — but when time and space have folded the way they have, productivity now online and a 24/7 gig, taken away are the parts of sleep that matter. By contrast, here, Sunday is a vibe. The exhibition atmosphere is easeful (the installation’s title, actually, is Sleeping with the moon), and the eye dilates to all this slow looking.

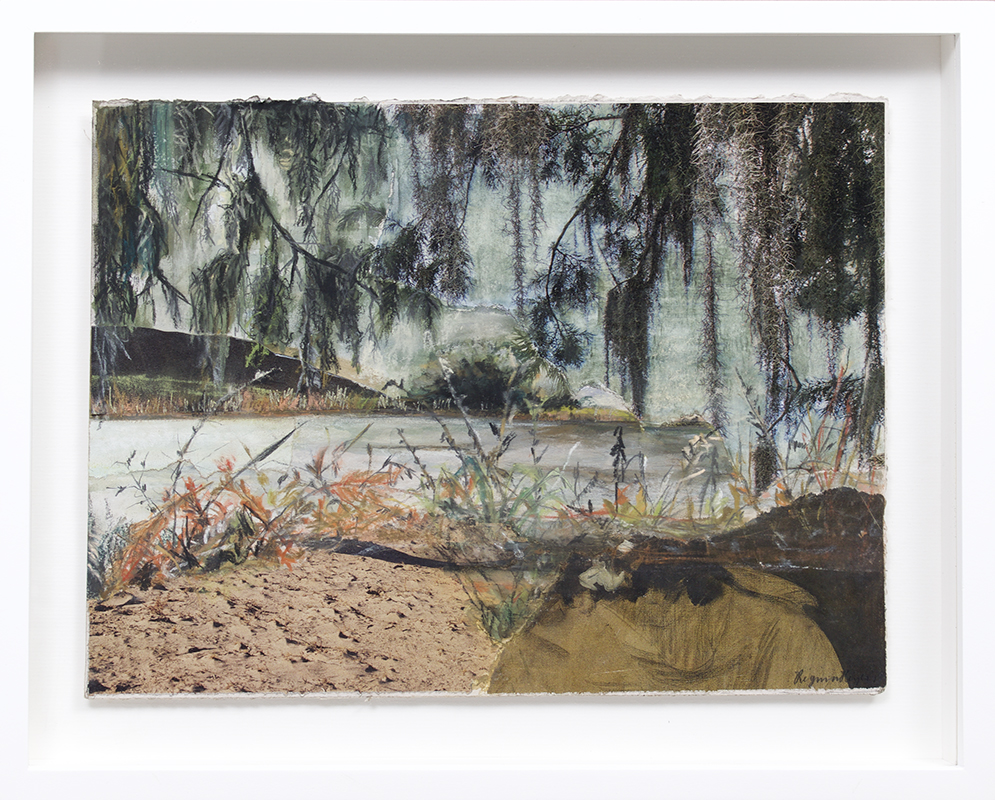

One thoroughgoing example is a mixed media work titled Do you ever wonder if the waters are really still, as it draws attention to a silver-white creek from the vantage point of a hollow beneath a canopy of leaves. The rest of the picture fills in. On the foreground’s left side is dry clay earth, painted farther back is an abstraction of a mountain. But it’s the tentative wording in the title (as much a show of Reyes’s writerly skill) that connotes and completes the fragility of the moment. It’s careful, as though if worded any more forcefully, not to disturb the water. Else the water would move.

The peace earned feels remarkably contingent. As with the other 13 small-scale mixed media works on display, no setting pertains to one actual place, though there are references. The images come from both magazines Regina had culled over the years and printed pictures from home and places she has traveled to, either by plane or bike. When making her collages, in contrast to how she plans her paintings, Regina describes her process as “being in dialogue” with her images — first laying them out on the table, then “listening” to the story they want to tell as she glues one after another onto the paper. Regina extends each cutout by painting after them. Although a tear in the outermost layer may clue us in on where the photograph ends and paint begins, the luminous effect is a thinned, almost sutured landscape. The sharpness of the images attenuates as the colors blend; the compositions are exquisite, spatially, for how the solidity of these landscapes recedes. The resulting sceneries are as genial and untenable as dreams: vivid, and one hypnic jerk away from smarting disbelief.

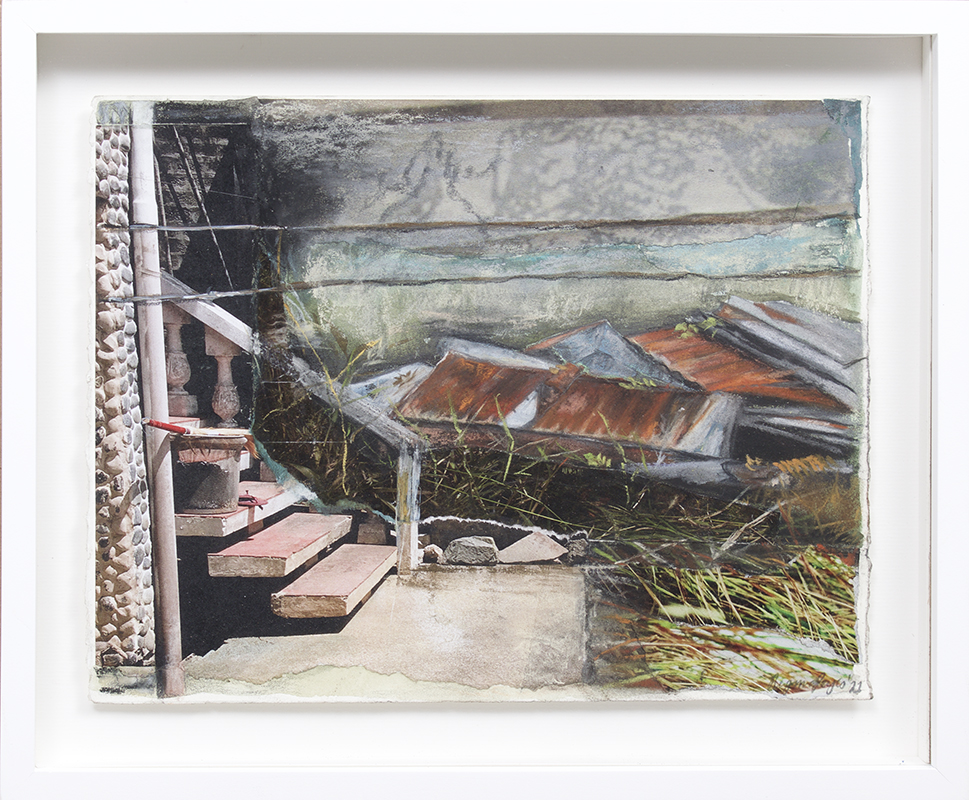

When asked about how her show connects with her continuing body of work, what crops up from Regina is a line from Gaston Bachelard: “In its countless alveoli, space contains compressed time.” The title of Bachelard’s book is equally koan-like. The general idea is that household objects and the spaces one grows up in (and is surrounded by) are intimate and infinite repositories of memory, by turns reconfigured by the newfound perspective that life experiences usher in. Exterior views of her house feature almost like anchors. Foliage, stacked tree logs, and overgrowths of flora settle and sprout over and about the perduring foundations of a battered house.

In a similar way, Regina’s practice (her collages and paintings, along with her sculptures and threadwork) often negotiate the tight braid between notions of identity and home’s place in it, stretching as far back as four years ago for her undergraduate thesis, and as previously in her breakout solo exhibition ‘Temporary Dwellings’, which explored the personal as political through her home. The home Regina had been born into is ancestral, situated across a parish in a small town in Rizal in view of the town plaza, and was something of an open house during the formative years of Regina’s life. The charms and generosity of the affable Noel Reyes, Regina’s father, endears his memory as much as town councilor as himself as a single parent of four daughters. People across town found work and shelter in the grounds, which, like the dining area and bathrooms, were often treated as communal space. When in want for privacy, Regina would visit her grandmother, who taught her how to sew.

The ancestral home began to empty when her father died, shortly after her grandmother did, and cascaded into its present quiet, around the time Regina had become a teen. For her UP Fine Arts undergraduate thesis, Regina assembled an upright piano from scrapwood, ridged with sawdust, with smoothed eggshells for its keys. Like the other life-sized works for that installation, the piano was replicated after the original in her home. It makes an appearance in All around time and in the same place and persists — perhaps less hauntingly — as a dilapidated tabletop for a set-aside walis-tingting. The materials used for the piano, in particular, were inspired by the practice of Bob Feleo, her thesis co-advisor, who observed that the thesis’s installation, though first intended to replicate the void left behind in her house, appeared more like a heaven in the outdoor grassy setting, a kind of afterlife. “Philosophies and practices, the environment and what people impart on you,” Regina explains, “it can’t be helped. They rub off on you in one way or another.”

The influences are extensive and, should she be believed, everywhere. Taped on the wall by the exhibition entry is a set of thirteen tiny vistas, diamond-shaped collages of various, dazzling colors that—for its title—invoke the first four lines of William Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence”: To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower / Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour. Despite what these lines might suggest of the poet, Blake was no mystic. His life was laden with financial worry and embroiled in the social and political changes of the time. Intertwined with his lifelong engagement with church and monarchy were personal challenges, such as the death of his brother, whose spirit Blake felt lived on in him. For Blake, activating the senses was the way to perceive the infinite, the spiritual past material folds.

To the tune of Bachelard, the calm, unfolding moment of Blake’s eternity seems — perhaps for Regina, too — to be the past recapitulated, or rather pastness coalescing, blurring the line between cause and effect. Instead, an unfurling, a change of viewpoint, one that, on occasion, becomes a form of rest. “You know, My mom’s name is Stella; I have a tattoo that says ‘estrella de la navidad’, which means star of Noel,” Regina shares. I can’t help it, so I ask her what she thinks of death. She replies, “Before, I thought of death in relation to coping mechanisms. It was too familiar, like it didn’t matter when it would happen to me. But now, with this life of my own I’m building, I wonder now what I would leave behind—my dad, until now, people love him, people like him still help us now—maybe that’s why I do art. I wonder if I could be like him in that way, and what my imprint would be, what, ten, twenty years from now, people would get from my works. Maybe that would be my legacy.”

Regina Reyes's second solo exhibition, No One's Rushing on a Sunday, continues until 23 July at Galerie Stephanie. All images courtesy the gallery.

Anchor photo: How I Go to the Woods (After Mary Oliver). Oil on canvas. 26 x 48 inches. 2021.