One look through the posts of Makò Micro-press would inspire the feeling of a dark, gritty, congested metro. “Makò” is short for manlalakò, or street vendor. Their pieces are mostly vibrant digital placards featuring slogans that call for social transformation through the community, their art akin to graffiti or subversive posters plastered on government building walls. Statements like “Walang Hustisya Walang Lunas” (No Justice, No Cure), written in angry white on a black background, scream a long-held exasperation—the cry of the most vulnerable during this interminable pandemic; “Hustisya ang lunas” (The cure is justice), Makò says. Bold, in screaming frustration, Makò’s art conveys a tired anger, an exhausted tolerance.

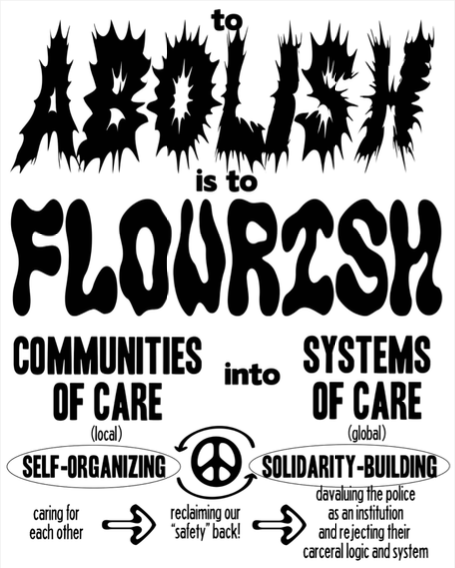

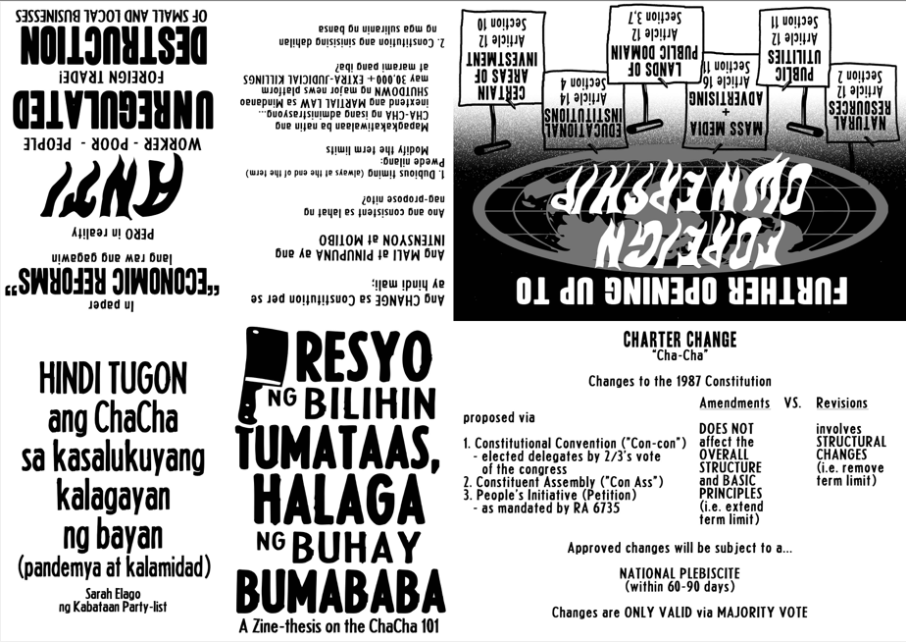

On World Press Freedom Day, a Makò tote bag carried a statement painted in red: “Gumawa ng zines, huwag matakot” (Make zines, be not afraid). Zines, according to Makò, are spaces where one could challenge dominant narratives. Recently they released free zines that anyone can publish and distribute: theses on the abolition of police and prisons, as well as one on charter change. Disenfranchised individuals and communities will find that they can exercise their right to speak through this uncensored medium. This follows the punk tradition of zine-making, where zines are used to distribute radical and progressive content.

Makò has been part of the art scene for a while—in almost every art fair I’ve participated in since 2016, they were also there, sitting behind what looked like a colorful bangketa shop. From BLTX to Komiket, they were present and ready. As a zine-maker myself, I’ve realized that one’s persona is exposed in the zine. The first time I traded zines with Makò, what I held in my hand felt like katipunero’s rusty bolo, a weapon that could cut. It was a black booklet called “sin ku wenta.” Contained in it are scattered prose and poems that, when read aloud, sound like rally chants. In #21, they begin their cry with, “Ang dumi ng kuko ko, malinis nga” (My nails are dirty; let me clean them). They call out governments and systems, and, finally, they end with, “Ang dumi ng mundong ‘to, malinis nga” (The world is dirty; let me clean it).

This metaphorical bolo cuts through a concrete mental jungle of deeply rooted thoughts. The smell of this jungle is the stench emanating from the clogged kanal system of a piss-stained city. Makò’s persona, expressed through “sin ku wenta,” braves the wilderness and points out the mess. They are difficult not to notice, for social awareness is intuitive. Makò’s work was recently featured in an exhibition curated by Marz Aglipay, called “To Even Out A Playing Field,” which ran from 19 February to 9 April 2021. The aim of the exhibit was to collect online work from 2020 that expressed artistic sentiments regarding the prioritization of certain projects during the pandemic. The section that featured Makò’s work was a table covered in black cloth, carrying candles and incense, on top of which were also two glass bowls: one had white powder, the other empty. Hanging on the wall above this somber, secular altar were six sheets of yellow paper arranged in an upside-down triangle. The three sheets on the topmost row featured the words “Resistensya” (resistance) and “Hustisya” (justice), written in shaky red ink; the final sheet spelled “Tagumpay”. Surrounding them were baybayin symbols and other stylish glyphs.

While the exhibition featured digital illustrations, comics, and zines, it made clear that engagement goes beyond likes and shares on social media: powerful art evokes a genuine emotional reaction that need to be shared. A zine-making workshop was conducted along with the exhibit, one of many Makò has done for students and communities, promoting free expression for various personal advocacies.

Makò’s work is deliberate, current, and brave. It shakes people awake in reality. But we have never really been at rest. Socially agitated artists such as Makò remind us to keep vigil. Though their concerns may not be answered within this lifetime, their presence reminds us of what we need. Beyond time and not limited by space, the words of Makò might be displayed in exhibits, heard in the streets, or held in one’s hand. Operating digitally, too, Makò’s accessible call for change arrives with startling urgency: their foundations are immovable and their action is now. Makò has a modest following, but a handful of people whose spirits are aflame have the potential to quickly invite others. There is no space for sarcasm or irony in Makò’s work: everything you see is as they are, perhaps even as they ought to be. In any case, for those who can’t find their voice, one might find their missing words shouted through Makò’s darkly contrasted work.