One night, during the six-month-long span she had been interviewing Hae Ryun, YuJin Choi dreamt that she encountered a master work by the painter, presciently titled The Wind Comes in a Thousand Ways: “the tour-de-force was not completed yet,” Choi recalls, “and it seemed like the painting was trying to embody within it the entire lifetime of a person.”

The interview, done in anticipation of Hae Ryun’s then-upcoming solo exhibition in Gallery Daon, Seoul (2020), was precisely for this gambit. A main feature in the multifaceted catalogue that accompanied the show, the interview was to be a firsthand account of the whole ten years of the artist’s professional career. The difficulty, however, was that this decade witnessed Ryun consistently reengineering her practice, deliberate acts which – through a later professed indebtedness to the ideas of Kandinsky – the artist saw as causal to her soul. In ‘Sense of the Absurd’ (2011), the solo exhibition featured oil paintings depicting dwellings lost to the slippages of time, not so much ravaged, but abandoned, saturated with colors such that they seemed underwater, taken by the sea. “Objects, people, memories, time… Once, I thought I could tie such things in place, but none of them would stay as they were,” the artist lamented in her statement.

That same year, the artist mounted an installation titled ‘The Angel’s Share Garden.’ Into “big, dying trees,” the artist planted pillars of mothballs and across them beds of these white, uniform, outsized beads. It was consolation, in part a matter of ritual: the naphthalene would eventually turn the balls into vapor, visualizing, over the course of a full season, a purification process to attend the grievances of death. Clear to Ryun’s followers was that the artist’s inquiries into transience, “the time of loss” and “loss of time,” maintained a direct channel to her works. “I want the essence, not the shell!” Ryun once exclaimed in her youth when she shifted from the fashion industry to art.

A year afterward, 2011, Ryun began ‘The Split of Moonlight,’ a series that took four years to complete, then exhibiting in 2016. The show signaled her departure from representational imagery and, resonant, words. It was a period of repeated brushstrokes and marked concentration in abstract compositions and aesthetics, a means for Ryun to present her “inner dimensions,” and the resulting works a preview of her developing interest in physicality – as with the visible involvement of her body – and demonstrative mediums: mother-of-pearl inlays (Najeon) and Ottchil lacquer techniques. “And,” the artist adds, “spontaneously, my interest in nature grew stronger.”

The pursuits of these came to fruition with ‘The Angel’s Share’ in 2018. The title refers to the phrase in wineries, preserving the belief that an angel comes by to help itself to a glass of wine, and was in part a call-back to the mothball garden: “When wine is aged in oak barrels, the water and alcohol gradually evaporates over time,” Ryun explains in a footnote, “Our lives are filled with numerous ‘times of loss,’ but perhaps we give those shares away to angels so that our lives could become more beautiful.” Landscapes trace of fallen trees in forests populated the canvas works, the view of them blurred at the onrush of winter winds, yet painted over these were multidirectional lines with geometric certitude – the influence of Sandback and Mehretu on the artist. Of the exhibition, a dear friend of the painter SungHee Kwon, remarked in his epilogue for the book: “They created movements… but these movements, where did they come from?”

“I want to give myself the gift of paused time,” the artist explains to Choi in relation, after reciting a passage of Thoreau’s poem, “Why I Went to the Woods.” But what began as a motive to capture became a thirst for captivation for Ryun, an altogether synesthetic experience to quell her insatiable love for art: “I, too, chose to live a life where I could indefinitely indulge in works of art, meeting all the new works as they come. I cannot call myself young anymore. Seeing how the life I’ve walked is paved with my deeds, it utterly breaks my heart.” And “only art could give this kind of relief,” the artist states firmly, “nothing else.” In a separate section of the catalogue, devoted as Ryun’s artist statement, she writes:

Life is something that never stops changing, something that never stops moving, something filled with perhaps too many occurrences. Incidents no older than yesterday are already blurry to us, and the past can be fathomed only through its traces. Reality is a severed and disconnected realm, and I had lost my way in it, almost devoured by the world, but then a gateway opened in the wall… the canvas was the door, and behind it lay a path that connected severed realms, a road that connected the past and the future… If a painting is finished, it means that the painter is gone… In one moment, I look at the things flowing toward here and wonder where they came from. In another moment, I yield myself to the things that flow away and see where they head to. Into the few pounds of flesh and bone that I am, I open the entirety of my mind, compile all of my past into a speck of dust, and glide away beyond the realms of reality.

This capacity to amplify existence – to transfigure the mundane and have it (somehow) yield meaning – had only once been so poetically rendered back in 1863, by Charles Baudelaire, whom Choi cites at the beginning of the interview: “Modernity is the transient, the fleeting, the contingent; it is one half of art, the other being the eternal and immovable.” Baudelaire had written it in a scathingly tone, too, one might add, as a clap-back to the staid art trends of his time, and, more pertinent, as contrast for his exaltation of the painter Constantin Guys. A minor artist in the eyes of the Salons’ beaux-arts trench coat brigade, Guys was, to Baudelaire, the “painter of modern life,” whom the notorious poet drew close affiliation with, and whose title as endowed had become eponymous for the seminal essay that had come presciently to define (by failing to) the interminable flux of an individual life.

The originality of one such aesthete who could distill the eternal from material culture belies a spiritual condition, which Baudelaire defines as that of an “eternal convalescent”: one who had as if “just recently come back from the shades of death and breathes in with delight all the spores of life” and become drunk with the details. But if it were for Guys the multifariousness of the crowd that vivified his beloved Parisian scenes, its

Enormous reservoir of electricity… which with every one of its movements presents a pattern on life, in all its multiplicity, and the flowing grace of all the elements that go to compose life… reflecting it at every movement in energies more vivid than life itself, always constant and fleeting,

For Ryun, it was her landscapes perfected. It was, to her, providence when Choi related her dream encounter of the masterpiece named The Wind Moves in a Thousand Ways. “When I heard those words, a wind rose in my bosom and penetrated through my heart, and it cast this image – ‘the wind is sounding…’ Your words described this new amalgam so accurately,” Ryun goes on, “and before I realized, the words had already affixed themselves like a seal.” From this dream came the name of the 2020 series; the fit to the “deletion of time” she so wanted to achieve; the name for the rhythm of life Ryun had, until then, only by her senses received:

As I inhaled the transcendental movement into my lungs, I was imbued with a wondrous sensation that my one, modest body, in fact, contained the whole, vast universe. Look how the blades of grass spread their wings as the wind brushes upon them! They show that life is none but in the act of living. At last, I perceived that I was a single dot existing in the universe.

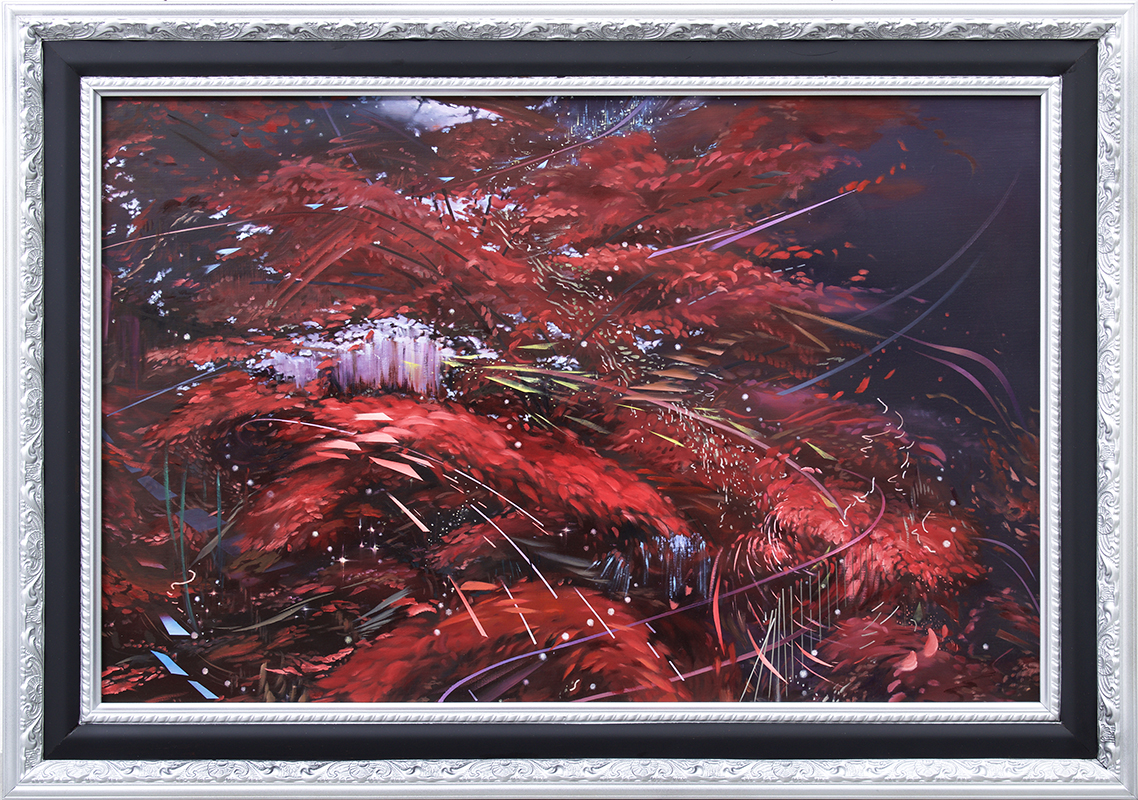

Banner photo: Icarus. 97 x 193.9 cm. Oil on canvas.

Hae Ryun is the latest artist represented by Galerie Stephanie. Her works, presented alongside those of Renz Baluyot, make up the third chapter of their capsule exhibitions for Art Fair Philippines, 2021.

All works presented and their images are courtesy of Galerie Stephanie, on view until today, May 15.

All cited texts related to Hae Ryun are from the catalogue, THE WIND COMES IN A THOUSAND WAYS. Translations to English are done by JaeHee Han. Copyright 2020 by MARI n MICHAEL.

1.jpg)