Began on 19 September last year, the 11th Berlin Biennale unfolded slowly as a series of three lived experiences, comprising workshops, exhibitions, projects, and talks. Through the 5 September 2020 launch of “The Crack Begins Within,” styled as the biennale’s epilogue, the running themes have since resurfaced and come together, with artworks spread across the biennale’s four venues until November 1.

The curatorial vision for the biennale came about “by asking how to celebrate the complicated beauty of life as the world burns around us.” As curators María Berríos, Renata Cervetto, Lisette Lagnado, and Agustín Pérez Rubio prefer it, attention shouldn’t be on the biennale-as-biennale. Rather, it’s how the process-based event makes space for shared experiences of dissent against patriarchal, colonial, and capitalist institutions, global forms of oppression that, along with their ramifications, continue to occur.

The result is an exchange between an overwhelming selection of artists, many of them female and queer, who identify or have been associated with the Global South. Four of them may be familiar to us Filipinos: Pacita Abad, Kiri Dalena, Cian Dayrit, and Brenda V. Fajardo. Whether you’re there or perusing online, navigating the art of any biennale can be dizzying. The curatorial statement of this one is particularly theory heavy—and for those among us who aren’t in the biennale (which is to say, most of us), those texts are all we have.

So, we figured, why not secure a better understanding of what’s going on by looking through the efforts and artworks by those closest to home? Here’s a read to help with just that.

Kiri Dalena

Kiri Dalena is both a visual artist and human rights activist. Her works document and provide critical commentary on the past and present state of national and political affairs. As early as 2001, Kiri Dalena co-founded Southern Tagalog Exposure (ST eXposure), an independent multimedia collective active still to this day. While ST eXposure primarily produces sociopolitical documentaries and audiovisual works—like Dalena herself—they also use more traditional forms of visual art protest (sculptural effigies, street theater, and mural painting) to promote the rights and welfare of the country’s marginalized and underserved sectors, shedding light on their struggle for social justice.

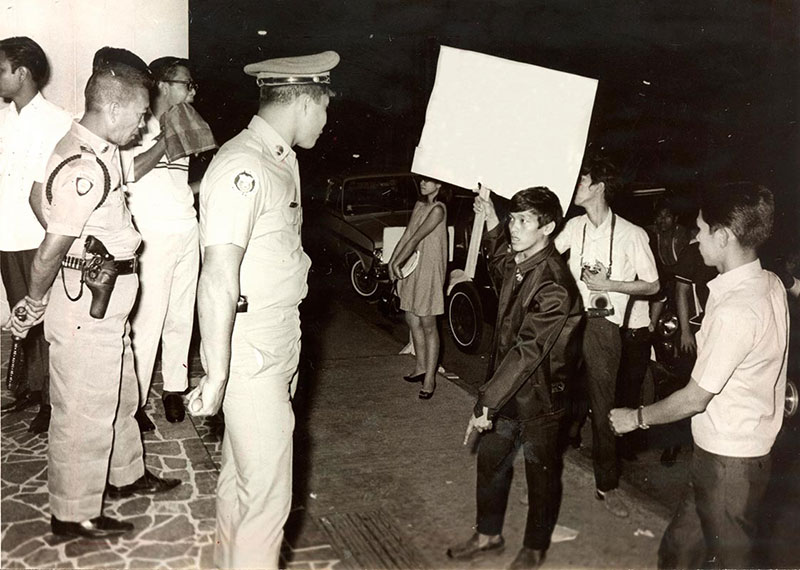

Kiri Dalena, of course, did not stop there. One of Dalena’s widely recognized works is Erased Slogans (2008-today), a series of digitally manipulated photographic prints documenting the Manila protests against the Marcos regime in the 1970s. Dalena’s reproductions of these archival newspaper images are near-exact; the striking difference is that she had deleted the slogans on all the placards. Left blank, these prints highlight the importance of protest, its timely virtue, as well as the silenced voices of dissent.

Come 2012, Kiri Dalena’s socially engaged practice took a significant turn with Tungkung Langit, as artist and writer Cocoy Lumbao explains for the Dalena’s biennale writeup. Tungkung Langit is the video work of hers on view at the ExRotaPrint venue of the Biennale. At the time of shooting the film, Dalena was accompanying relief efforts for a remote village in Iligan, then-devastated by a hurricane:

“With the community’s encouragement, she found herself documenting two survivors, both young children—siblings who had lost their family in the tragedy and were left to cope on their own. Realizing the fragility and vulnerability of her subjects, Dalena found herself reevaluating the filming process to find a more compassionate form of taking part in telling their stories, and she began to join the children in drawing and making art.”

That compassionate form for storytelling continues in Dalena’s latest video work, Alunsina (2020), in which she documents the struggles of children and families severely impacted by the present war on drugs. It is likely not a coincidence that Tungkung Langit and Alunsina are the names of Visayan deities, both of whom feature in a variation of the Visayan creation story. In a recent feature on CNN, Dalena explained that the 2020 film was titled after the god to give power to children and the elderly.

*For those interested, Tungkung Langit is on view online and for free from October 2 – 8 through Daang Dokyu, the ongoing festival for Philippine documentary film.

Cian Dayrit

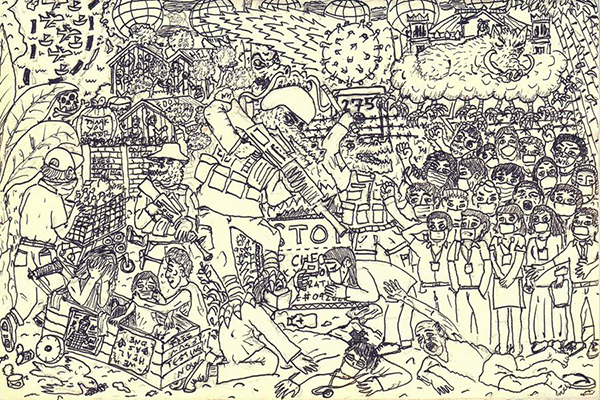

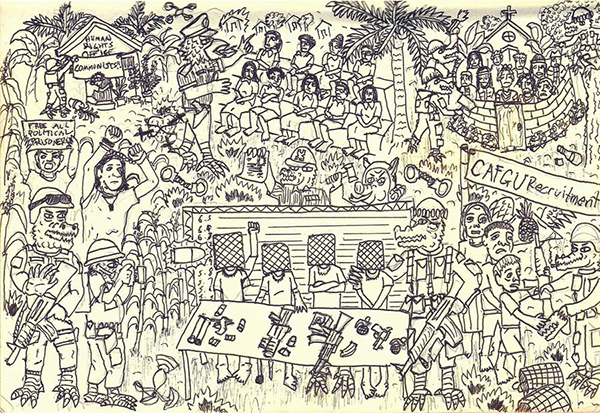

Cian Dayrit’s interdisciplinary practice reveals the colonial, political, and cultural lineages that attend common beliefs, and how present visual strategies and modes of representation perpetuate such histories by their omission. He tackles, in our understanding, the underlying systems behind the production of knowledge (consider, Foucault’s appropriation of Nietzsche’s genealogy of morals). Dayrit’s first major solo exhibition, The Bla-Bla Archaeological Complex (2013), for example, presented lost artifacts of a fictional culture, while utilizing the context of the Vargas Museum venue and archaeological lingo to show how convincingly such fictions become legitimated.

In 2015, Cian Dayrit held a solo exhibition with Tin-Aw, titled Spectacles of the Third World, which revolved around the Philippine fiesta as an appropriated environment. By this time, Dayrit had tied a thread between fictive archaeology and folk millenarianism, exploring ways to better apprehend them both as manifest phenomena, as well as critique, of hegemony (or, if you prefer it, empire). As curator Lisa Ito writes for the exhibition’s accompanying essay, “Forays into Postcolonial Pastiche,” “For Dayrit, the process of rumination continues beyond the creation of structural narratives. He fills the gallery space with more such questions from the peripheries: chronicling and collecting his own discrete responses to both the colonial encounter and to the entropy permeating Philippine contemporary life.”

Several exhibitions and a triennial later, with a Gasworks artist-residency in 2019 to cap it, Dayrit had by then turned his attentions to counter-mapping as a way to engage with communal memory and forms of state power and control. Power, in its foundational sense, has always rested with who owns what land, that person’s vision for its development and—by extension—the conditions under which people are permitted to inhabit that space. Dayrit’s infographic quilted map as exhibited in the biennale, Tropical Terror Tapestry (2020), sees all these elements come into play in the work’s flat composition: folk spirituality, state apparatuses for terrorism and militarism, and how these and more turn countrymen against each other in service of, essentially, white mythologies.

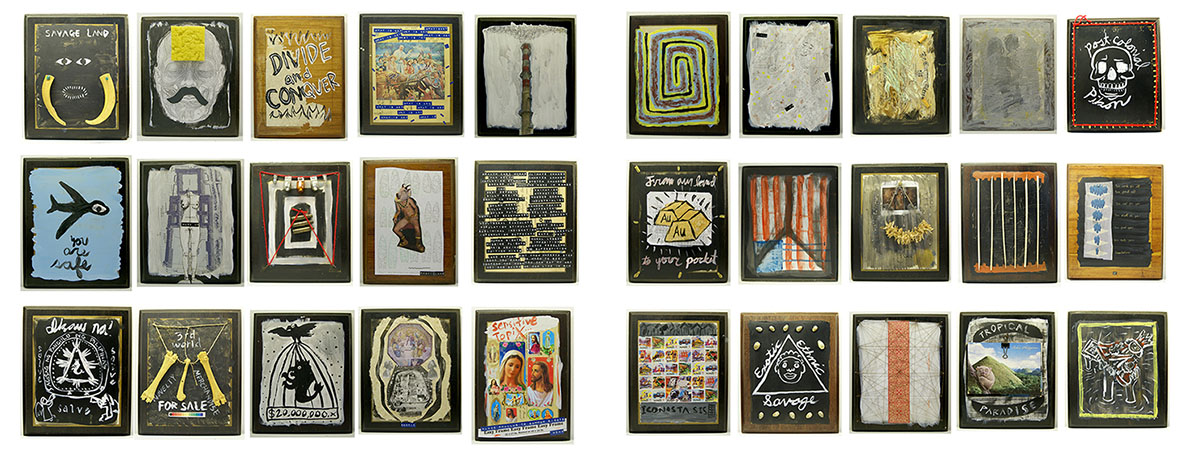

Brenda V. Fajardo

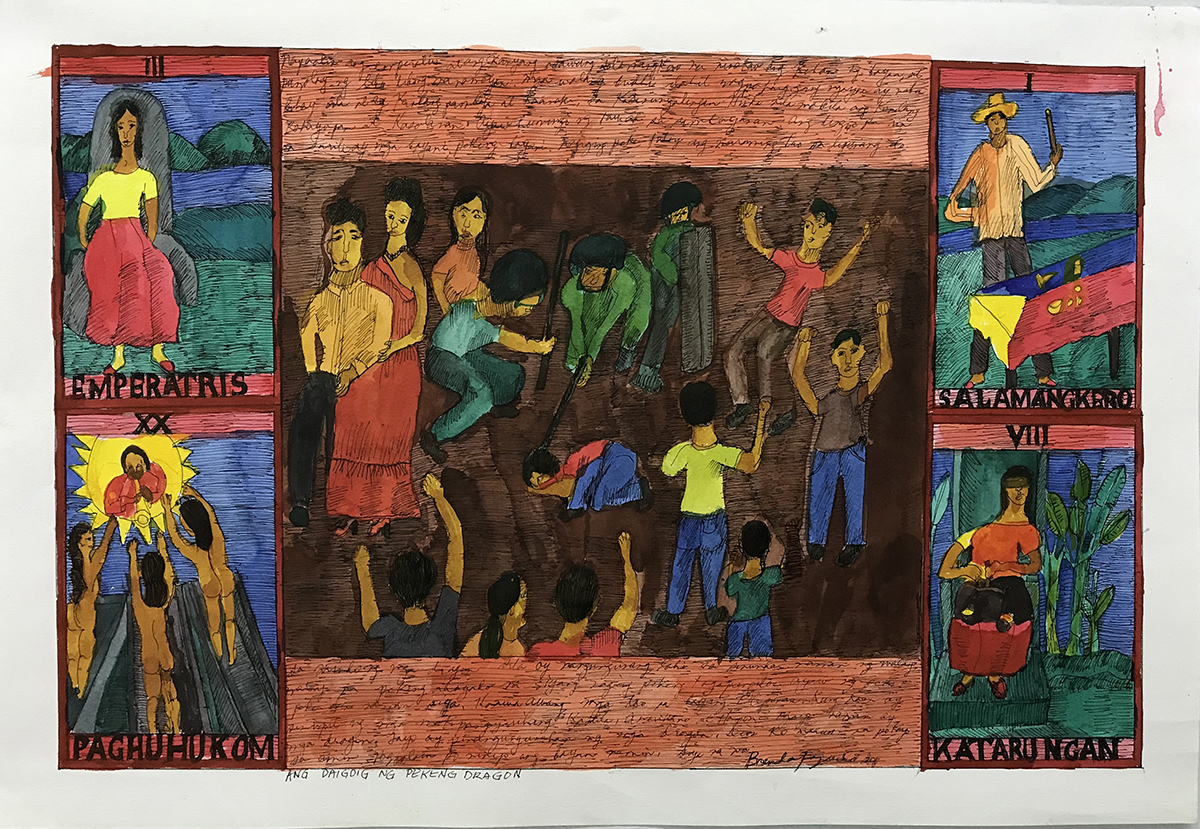

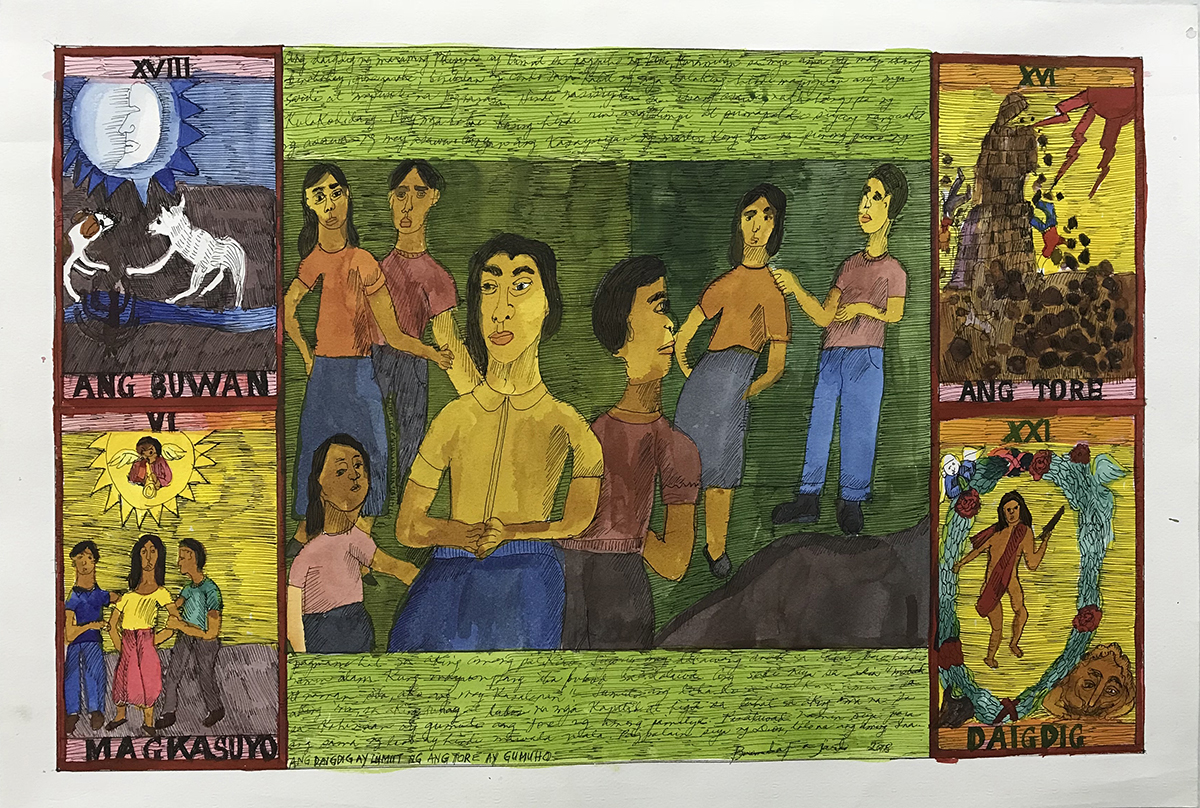

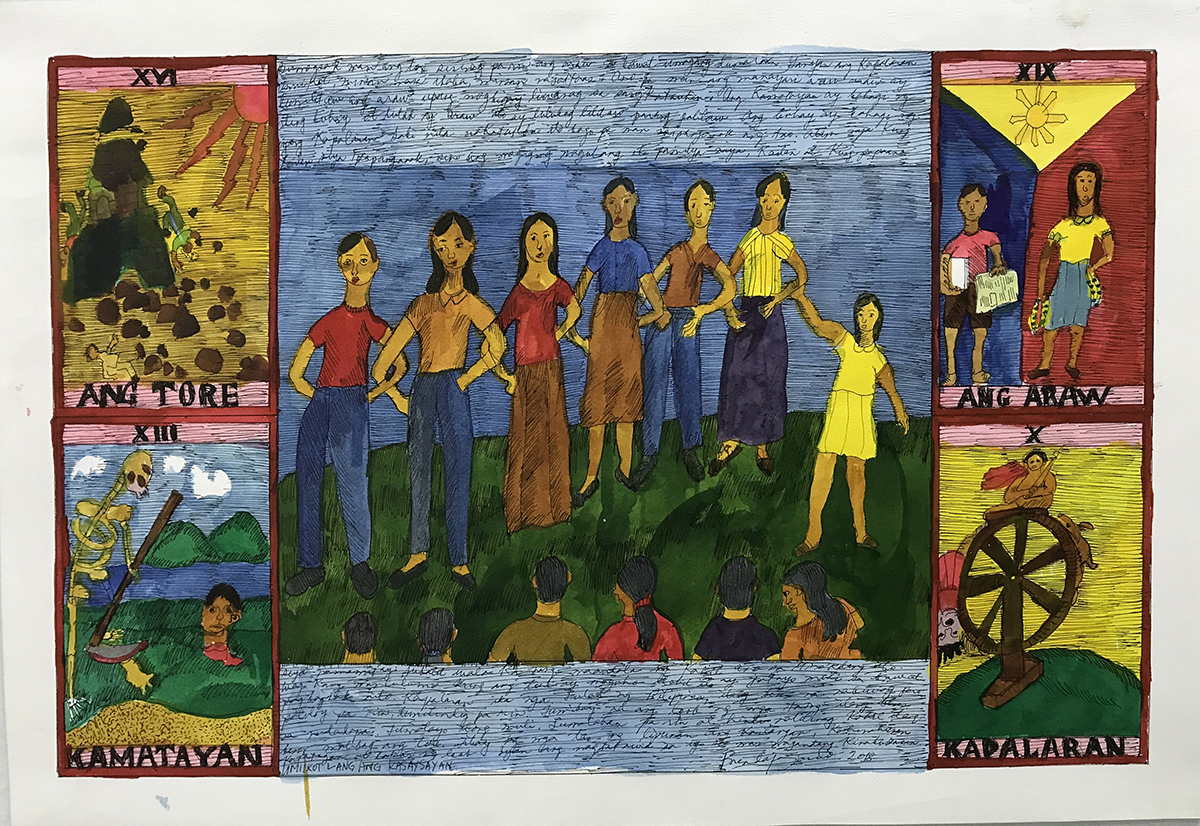

A painter, printmaker, and graphic artist, Brenda Fajardo is best and rightly known for her longstanding series of tarot cards, Baraha ng Buhay Pilipino (Cards of the Lives of the Filipinos), on view at the biennale courtesy of Tin-aw. By appropriating the symbolism of the tarot through these works on paper, as Joselina Cruz writes for the artist’s biennale writeup, “Fajardo embeds the imagery within the local and power within the feminine.”

Fajardo’s appropriation of the tarot—the cards themselves often considered as archetypes—goes the extra effort of including the names of individuals in her titles. The specificity accorded to naming, Cruz continues, “absolves Fajardo’s works from simply being representative of circumstances and events,” such that, even as sociopolitical and colonial struggle with folk elements intertwine (for example), the oracular potency of Fajardo’s cards isn’t too cloaked with mysticism to address current or recent issues.

A stellar example is presented to us through 856G gallery’s feature on the artist. Fajardo’s version of the major arcana member, “The Fool,” is translated into its female indigenous version, “Ang Gaga,” symbolizing the babaylan, a precolonial mediator between the physical and spiritual world. In the feature, this leads to a discussion about Papa Isio, both a babaylan and revolutionary icon who had fought against our Spanish and American colonizers. These common gender reversals in Fajardo’s art tie in with her feminist alignment. Brenda co-founded KASIBULAN (Kababaihan sa Sining at Bagong Sibol na Kamalayan), a feminist collective still strong today, with contemporaries Imelda Cajipe Endaya, Julie Lluch, Anna Fer, and Ida Bugayong. Fajardo had also helped Rudolf Steiner (a contemporary of Rizal) establish his Waldorf school in the country. According to art academic Flaudette May Datuin, Brenda Fajardo also founded the Baglan Community Cultural Initiatives, helped pioneer the street theater group PETA, and was an advisor to the NCCA.

Click to read the transcriptions and translations of Fajardo’s artworks, courtesy Tin-Aw Art Management Inc.

Pacita Abad

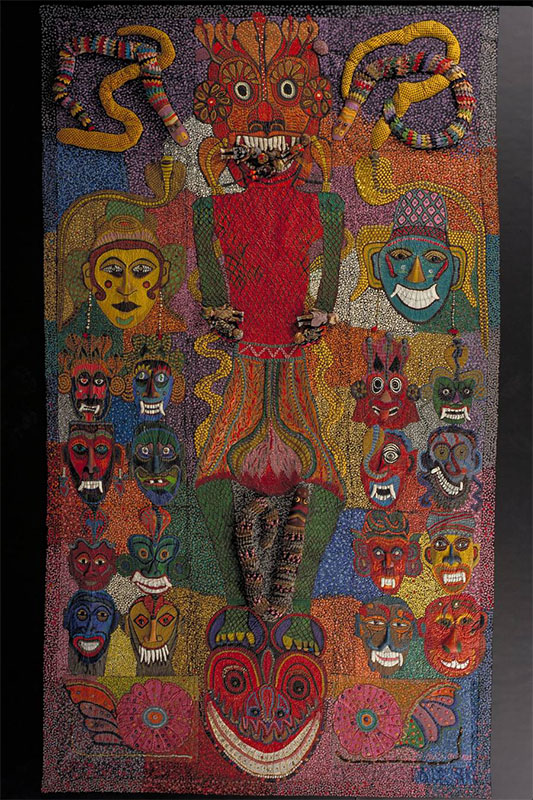

The work featured above is the largest work of Pacita Abad’s exhibiting trapunto painting series, a style she explored in the last two decades of her life (1981–2000). Entitled “Marcos and His Cronies,” aliased “Medicine Man,” the work took ten years to complete. As curator Agustín Pérez Rubio explains for the writeup, “the dictator [indicated at center] appears surrounded by eighteen grotesque masks that represent various members of his cabinet as well as his wife, Imelda, whose bright earrings refer to her notoriously lavish lifestyle.”

Sewing and textile have long been gendered as “female.” We find this premise explored and interrogated even today, with artists like Patricia Perez Eustaquio utilizing textiles in their present practices. Avid Pacita fans (aren’t we all?) would be quick to note that the trapunto style, though, isn’t native to the country. It’s an old Italian quilting technique that Abad inverted to provide the paintings a sculptural dimension, the elements of which contain African, Nepalese, Tibetan influences, among others.

Abad’s art practice served as markers of her itinerant life over the years, indicative of her increasingly global sensibility. Her activism when she was a political science student in UP Diliman didn’t sit well with her parents—as nephew and artist Pio Abad confirmed in 2018—and so she was sent to the United States. While there, Pacita married and, with her husband at the time, traveled. By the time she returned to the States in 1976, she decided to be an artist, and a nomadic one at that, picking up styles and art forms wherever in the globe she went.

Learn more about Pacita Abad through her website.