Space is the silent, essential partner to thinking. We can hardly speak without some form of spatialized logic. Through expressions like “looking back,” “thinking ahead.” “moving on,” for example, we have conceptions of time made. We cut, divide, and order ideas through space.

This is no better done nor visualized than in the wonderful art of Jem Magbanua. Introspective, calm, powerfully affective, Jem’s works give us a ride into the slipstream of how space connects us. For this interview, we look into what makes her visual vocabulary, as well as what it means to embody a place and, possibly, belong in it.

Cartellino: Grown up in the Philippines, studied in Singapore, and a participant of three art residencies in Japan. How do these settings and experiences figure in your art, which has so much to do with space?

Jem Magbanua: Contending with such differing degrees of experience in these spaces naturally translated as sets of tension present within my work — tension between interior and exterior, natural and artificial, order and chaos. My experience of Manila is that of a bustling, cramped, restricting space. Singapore was fast-paced, synthetic, flashy. Japan, on the other hand, was quiet, expansive, and untroubled. Living in each place did not just expand my physical horizon but opened up new, inner landscapes to explore — states of mind that rise up to the fore while dealing with the foreign.

C: We can’t help but make comparisons with the geometric planes and flora in both A Topology of Everyday Constellations and Garden, City or Wilderness. Would it be right to say that the themes of one build from the other? Is the use of color in Topology an important distinction from the mainly graphite artworks in Garden, City or Wilderness for you?

JM: Indeed! My series are simply progressions of the same narrative. I am always trying to forge better ways to depict it. But you’re right on track. A Topology of Everyday Constellations was a direct continuation to Garden, City, or Wilderness. I wanted to see how I’d take on the subject three years later.

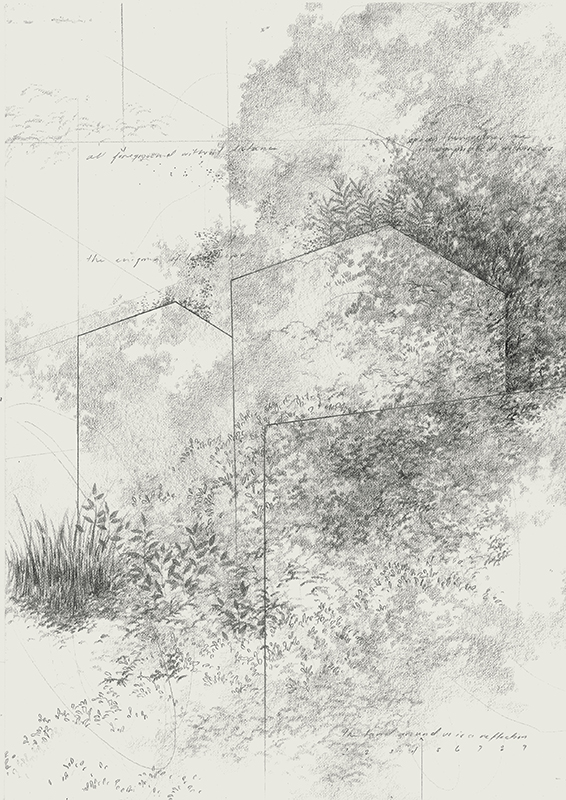

Garden, City, or Wilderness was a general exploration of the malleable metropolis that is Singapore. Dutch architect and theorist Rem Koolhaas wrote of the “tabula rasa” phenomenon, a term for ultra-modern cities like Singapore, that undergo continuous demolition, renovation, and construction. I was interested in this build-from-scratch method resulting in a city highly acclaimed for its aesthetic appeal yet lacking in its precolonial history. There was no choice but to look forward since there was barely anything left to look back on. This state of constant renewal and temporality was what I wanted to capture in that particular series.

A Topology of Everyday Constellations continues my previous show’s play with ideas of time, temporality, and transformation but in a more domestic setting. I specifically looked to the writings of Walter Benjamin describing how the rise of modern urban life was accompanied by a parallel turn toward the private individual. The modern interior became “the inside location of people’s experiences of, and negotiations with, modern life” (Penny Sparke) — a place for inward reflection and awareness. Perhaps the infusion of color in this series is attributed to the “grounded-ness” we find in domestic spaces. There was a natural need to give the depicted objects more fullness.

C: In an Instagram post of yours about Ghost Geography, you mention how the imagery you deploy is reminiscent of your upbringing. Can we ask what your process was like making the artworks for this exhibit? Was art, too, a big part of your childhood?

JM: Ghost Geography is an exploration of the immediate environment right outside my doorstep — a particular type of residential sprawl that slowly encroaches on the outskirts of the city. These neighborhoods are kind of like worlds within themselves, Disneyland-like gated communities that feel as though they were graphed from the mountain villages of Italy or the suburbs of America. When entering a community such as this, one is almost thrusted into a continuous oscillation between belonging and estrangement. ‘Belonging’ in a sense that one feels like a part of a homogenous community of themed homes, yet estranged by the fact that these picture-perfect looking homes speak little of the larger context in which they were built in. Whenever one steps into such gleaming establishments, I frequently hear that it “doesn’t feel like you’re in the Philippines.” It feels foreign in a domestic sense. I suppose as a third-culture kid, I relate very much to the feeling of both belonging and estrangement; the outsider looking in.

These ideas helped shape my focus on the architectural motifs in the neighborhood- pristine white exteriors with dark-colored accents and roofs — a simplified symbol that harks back to the quintessential modern American home. There was also the use of thick, high foliage as one, a makeshift fence to protect the seclusion of one’s home and two, a border around the neighborhood.

Yes, my childhood was woven with art. Growing up as a keen observer, I always had the urge to record the things that captured my attention. Drawing came as the most natural form to explore these experiences. It allowed me to understand the world in-depth and became the language I felt I was most proficient in.

C: One observation in your works is the absence of people. Yet, we find traces of them: an empty chair, a garden, a potted plant. Can you tell us more about that?

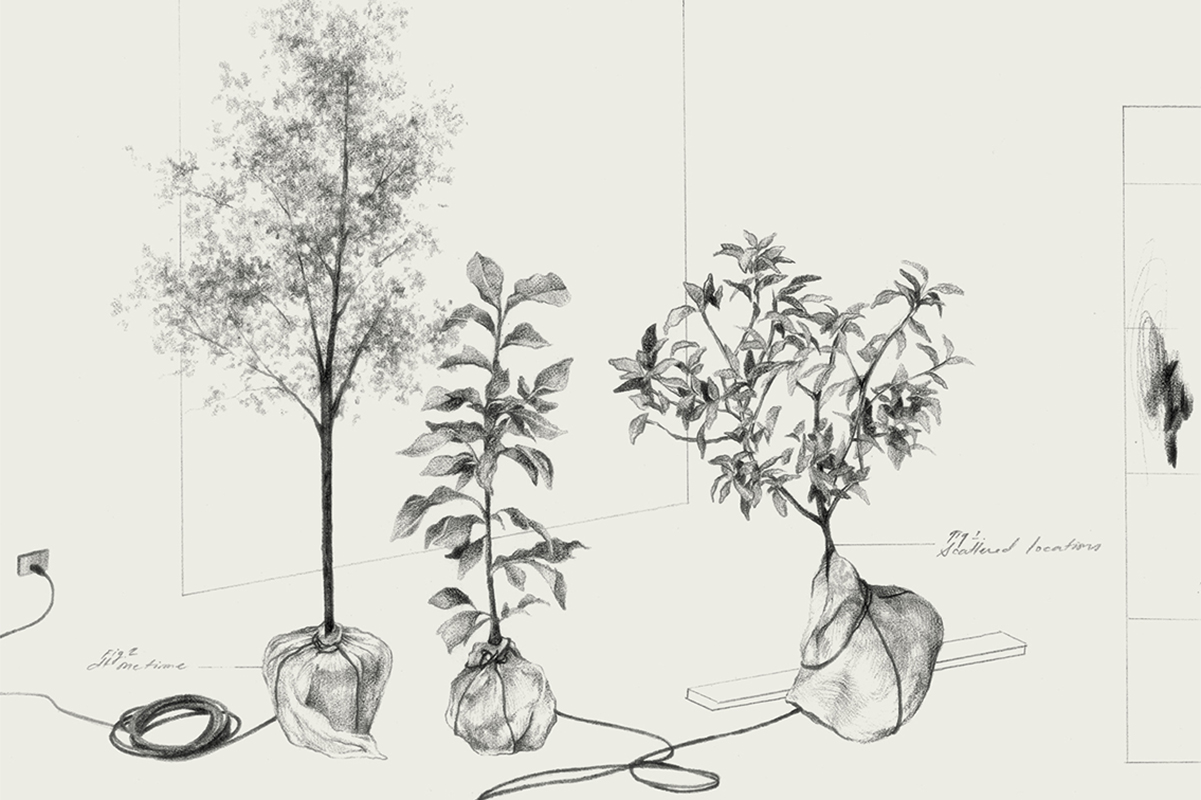

JM: In pursuit of exploring the human psyche and its connection to the landscape, I looked more at objects and designed spaces instead of simply looking to the persons themselves. I am particularly interested in the way such things serve as representations of various states of mind.

For the series, A Topology of Everyday Constellations, chairs, in particular, drew my attention. It has a long history in fine art — being the subject of scrutiny for painters like Vincent Van Gogh all the way to David Hockney. Such painters depicted these inanimate objects with as much intimacy and purpose as their portraits. Just like people, chairs have arms and legs, too — making it adequate enough to carry some form of character, emotion, and sentiment.

As for the potted plant that consistently finds its way into my work, I always relate it to my own ideas of “home”— comfortably grounded in its own little pot, the plant is not rooted in a particular terrain. It is an ecosystem within itself. In that sense, living in two different countries resulted in me not fully rooting myself in a particular place. My idea of home is more like a state of mind I carry anywhere along with me.

C: We are as much fans of your artworks as we are of the writing that accompanies it. There’s a quality to your writing—whether your own or a choice quote from someone of a ‘like’ mind—that really completes the affect your works convey. It’s reciprocal. Can you tell us more about that relationship?

JM: I consider myself a frustrated writer. So in that sense, I continuously attempt to make inroads within the vastness of what I cannot put into words through my art. My intuition is highly sensitive to that gray area. So, I feel as though I hit bullseye when I find a quote that perfectly describes a drawing of mine that resulted from some ambiguous feeling derived from disparate origins.

There’s a fullness and power in giving words to something.

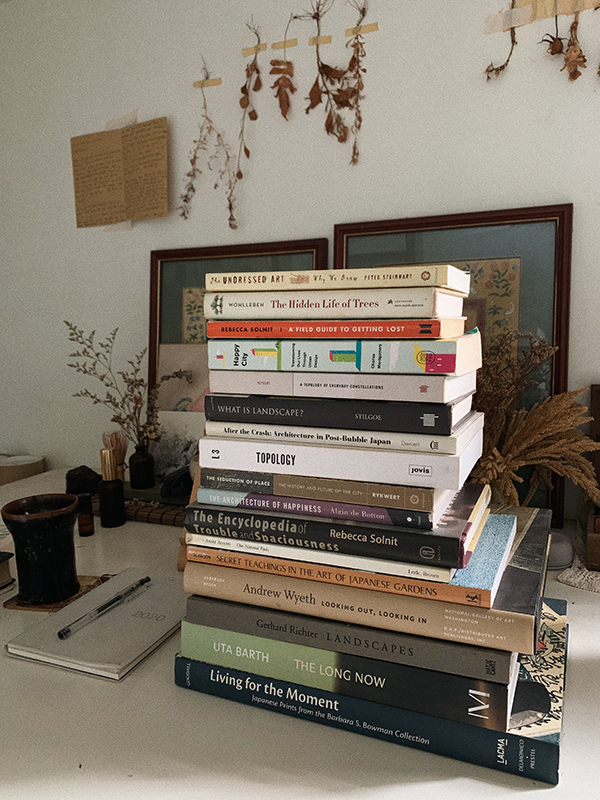

I also enjoy the art of investigation — my research is not simply a means to an end. There is so much richness in spending time researching that it can be a creative act in itself. I consider the works I create, in turn, as another form of investigation. In order to better understand an idea, not only do I have to read and write about it, but I also have to give it a form.

C: How about horticulture, both in your art and your life?

JM: My childhood home was a place of avid respect for cultivation. To this day, our garden is filled with banana, guava, papaya, and avocado trees, along with chili, kang kong, and basil (just to name a few). It was my Dad’s particular fascination with bonsai that thrust me into the world of indoor plants. I was intrigued by his unwavering attention on his dwarf tree, contemplating each branch and its contribution to the overall aesthetic form before proceeding to prune it.

In my artistic practice, I am interested in our natural bent to cultivate the landscape. Not just to appreciate it from a distance but to have it invade our personal domestic spaces. It’s our tangible way of connecting with nature without having to contend with the harsher natural elements that these plants typically thrive in. There’s also that ambiguity between horticulture and decoration that indoor plants particularly occupy. It can serve as an ornamental piece and, also, as a symbol of a certain political or social standing.

C: What does it mean for a person to occupy space?

JM:

“To walk is to lack a place. It is the indefinite process of being absent and in search of a proper. The moving about that the city multiplies and concentrates makes the city itself an immense social experience of lacking a place… Ultimately, the place but is only a name, the City ― a universe of rented spaces haunted by a nowhere or by dreamed-of places.” ― Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life

I don’t know if I’m answering the question by saying this. Still, I think — after reading philosophers like Kant, Heidegger, Hegel, and a multitude of other contemporary thinkers — that we will never be fully satisfied with that which we call home. We are consistently forging new homes in people, in places, or in things to satisfy our longings. Which makes me believe that perhaps we are made for a place that ultimately isn’t material.

C: Last question. Among the thinkers you mentioned, it’s interesting to see how Benjamin and de Certeau were singled out. Notably, in your thoughts on space, the withdrawn psyche, and the ‘uprooted’ yet sustained self.

It reminds me of the ideas proposed by a similar thinker, Lefebvre, in the way they’re used in David Harvey’s essay, “The Right to the City.” For Harvey, we change with the city; in step with urbanization, “we have been re-made several times over.”

JM:

“We shape our building, and afterwards, our building shape us.” ― Winston Churchill

This current pandemic has made the politics and quality of our built environment incredibly visible. We are currently living in a time where we have to rethink our physical spaces now that we are confined to our homes. We used to have to contend with the flux of the outside urban environment. These days, we forge ways for life to somehow go on within the restrictions of our domestic spaces. There are two shifts I have noticed, for those of us who are fortunate enough to stay put in the comfort of our own homes:

First is a re-grounding of oneself in the local (on the scale of home, building, subdivision, barangay). My own neighborhood’s entrepreneurial sides have heightened where food, desserts, fresh produce, and supplies are up for grabs. This has allowed people to take the time to walk to one another’s houses as opposed to hop into one’s car and drive to the nearest mall. People are making use of their available patches of soil to grow their own crops. This situation of being grounded is re-grounding people’s values in relationship to their immediate landscape.

The second, on the flip-side, is an escalated migration towards the digital realm. Cultural, social, and economic activities and processes are steadily being translated into networked environments. Home delivery services, Viber communities for “hard-to-find” supplies, online classrooms, Minecraft virtual music festivals, Netflix Parties, and Zoom weddings, reunions, and church services. There is an intensified need to satiate the hunger for human contact.

Once again, we have to re-make ourselves in line with the new structures in place. Perhaps these are all aspects of a potential new normal as we navigate through our environments, post-pandemic.

Jem’s archival print,“Civil Twilight,” is available at the Cartellino shop.

All images courtesy the artist. Follow her on Instagram!

For Zero Hunger PH

We thank the artists Kiko Capile and Manix Abrera, as we happily pledge part of the proceeds from our “Athena” and “Mandirigma ng Dalam-Hati” tote bags to Zero Hunger PH’s crowdfund. Zero Hunger PH is a youth-led movement aimed at creating and distributing food bags to the homeless and families at risk, following the ECQ’s suspension of work.

To learn more about initiatives like Zero Hunger PH, Help From Home PH is an online information hub that connects people who want to help with people who need it the most.