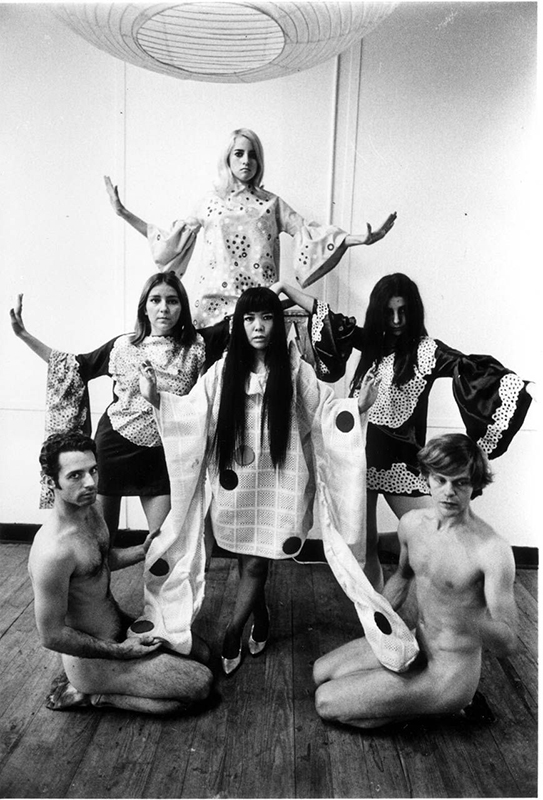

Vehemently opposed to America’s ongoing war with Vietnam at the time, the year 1968 was when Yayoi Kusama staged The Anatomic Explosion right across the New York Stock Exchange. One of the many notorious ‘happenings’ (a then-widespread, mainly western, phenomenon coined by Allan Kaprow), Kusama’s performance art, in particular, was to draw attention to the establishment funding the war, and draw attention it certainly did: the performers, along with Yayoi, danced in front of the Washington monument nude, adorned with Kusama’s signature polka dot patterns as body paint.

Bombast and nudity aside, in situ art projects and chance happenings have a unique capacity to communicate both in ‘the real world’ and at an aesthetic remove from it, which, as a mode of address, tends to turn heads more than the issue when otherwise left alone. As an impermanent art, the avant-garde performances antagonistic to the times’ political unrest is a critical antecedent for how participatory art is understood, almost intuitively, by most today.

In the general run, the rules of the art game fall resolutely under ideas of authorship. Traditional critics and scholars write based on an artist’s oeuvre; an artwork’s value skyrockets when authenticated. A more contemporary example would be an urban art mural cordoned off until Pest Control verifies it as Banksy’s. Generally, we—the spectators—need to know who a work is “by.”

When participatory art came, it came provocatively, hefty with the promise to overturn the conventional triad of artist-object-viewer. The genre takes as many forms as it overlaps (interventionist, community-based, littoral, etc., coinciding with the boom of new technologies and media), the linking feature is in collaboration—in ceding authorship and control, often for a horizontal social model or convivial setting.

It’s inherently social, often a mode of protest; its enactments and reenactments, contingent on the space and who’s in it. It can’t be framed or hung, while documentary accounts of the act rarely do more than serve as a visual proxy of an experience long gone. As it is with performance art, participatory art (for ease of use, let’s keep it at participatory) takes its force in the social relations generated—unpredictably—by the shared experience of the act. From the get-go, its principles lend a lot to democratic ideals, but can art function the same as actual social practice?

In various degrees, binaries of artist/viewer and art/life blend and shuffle in these site- or community-specific projects, along with a swap between object-oriented mediums for living participants. Breaking the fourth wall closes the distance. The critical kind. If the painting is thought of as the spectator’s object for contemplation in passivity, participatory art called for artists to make and complete works with people, instead of ‘for’ or ‘about’ them.

Artists set the conditions and premise, but they can’t control the outcome. Rirkrit Tiravanija, in the 1990s, began a series called Untitled (Free), where the artist would serve pad thai noodles to the gallery’s attendees. Xu Zhen, in his XuZhen Supermarket, on the other hand, is of another kind. Replicating a Chinese convenience store, Zhen and company outfitted the store with familiar brands and products. The contents, however, were empty, yet the store found customers all the same. The press releases are quick to note Debord’s idea of the spectacle, as “capital accumulated to the point where it becomes an image.”

Through voluntary participation, we can call these two distinct events as participatory art. Where Tiravanija works on the positive symbolic act of collectivism through a shared meal among strangers, Zhen finds his audience literally—enthusiastically, even—buying his satirical act. Sotheby’s 2018 article, “Experience the Art of Emptiness with XUZHEN Supermarket,” ends with the auction’s opening estimate: (115,000-192,000 USD)

When you break the fourth wall, how much of the world’s rules do you let in? How ought we react to artworks that detract from the familiar—ostensibly independent—realm of aesthetics and veer into the ethical? When “good” participatory art is judged based on its positive ethical implications, how long can the threshold of just raising awareness safeguard artists’ intentions? At what point is it what we call clout?

Look at the title. Where do we stand with participatory art?

Anchor photo: Xu Zhen. ShanghART Supermarket. Installation view. 2014. Image courtesy ShanghART Gallery.

For Zero Hunger PH

We thank the artists Kiko Capile and Manix Abrera, as we happily pledge part of the proceeds from our “Athena” and “Mandirigma ng Dalam-Hati” tote bags to Zero Hunger PH’s crowdfund. Zero Hunger PH is a youth-led movement aimed at creating and distributing food bags to the homeless and families at risk, following the ECQ’s suspension of work.

To learn more about initiatives like Zero Hunger PH, Help From Home PH is an online information hub that connects people who want to help with people who need it the most.