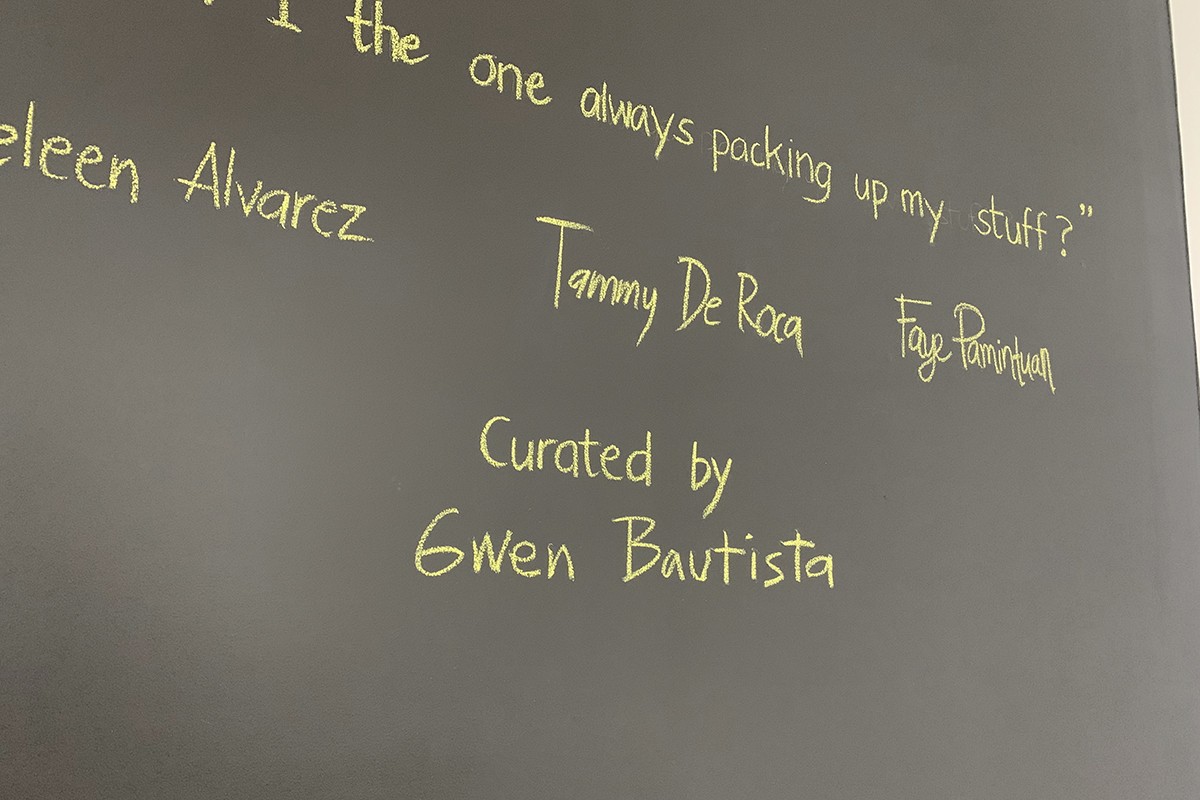

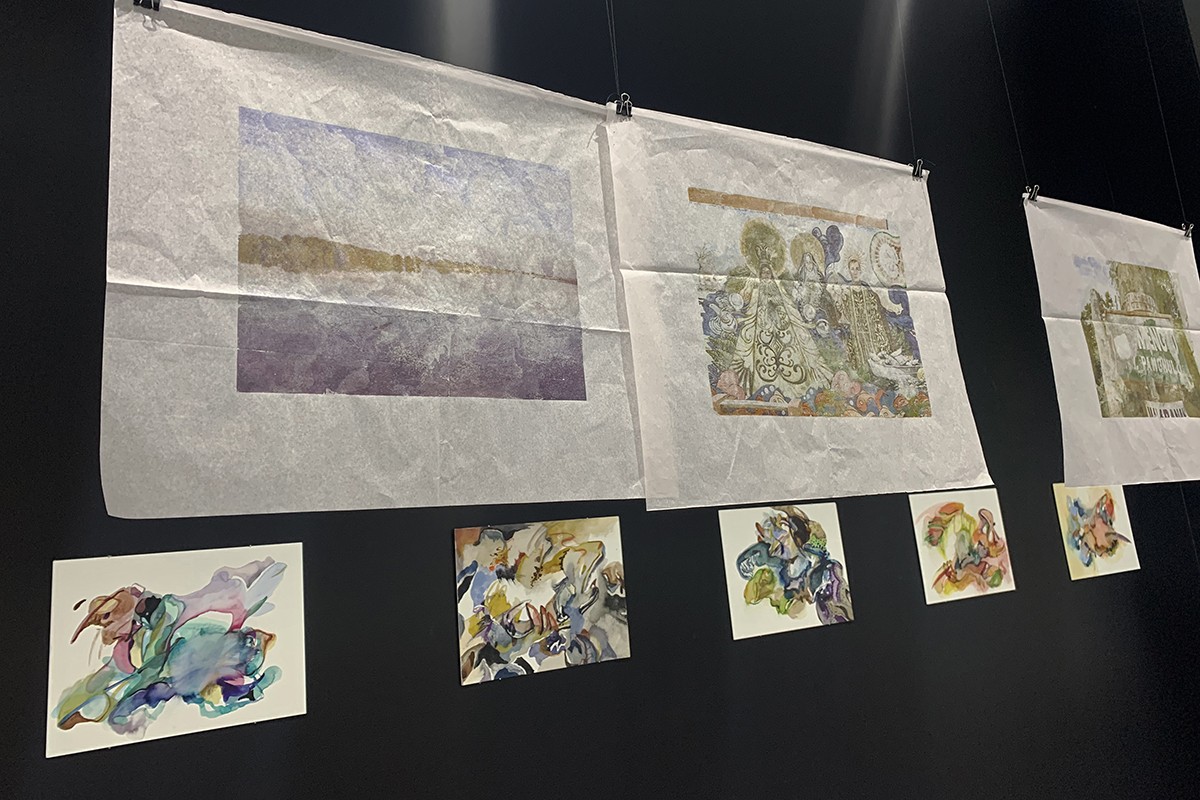

Artinformal Greenhills was packed when we arrived. You'll immediately spot the famous fishball vendor right by the entrance. A few familiar faces and we head inside where the exhibition was held. We were told that this was probably the most political exhibition they had to date; it's one that's upfront and direct. It was the opening night of Souls, Soil, and Sea. One of the galleries inside featured works from about 100 different artists from all around the Philippines. They called it The Newsfeed Project. The same night, we met its curator and pioneer, Gwen Bautista. It was The Newsfeed Project's second exhibition; the first was in 2018 held at Tam-awan Village, Baguio City. The exhibition filled the room with 1:1 works and as its title suggests, it looks exactly like a typical Instagram discover feed, only with sociopolitical implications and more freedom than the app would give any of its users. The show, meta in its sense, revolves around sharing art as it's being shared online; it's for everyone's consumption, free of charge. It brings back art to its people envisioned by Bautista with the help of her friends in the industry as a curator and artist herself.

"Calling myself a curator means I welcome criticism and the accountability to the exhibitions I curated."

Before she is a curator, Gwen Bautista is also an artist. She studied Fine Arts major in Painting at the University of the Philippines and participate in exhibitions as an artist as well. As anyone who is new to the task of art curation, Bautista was then hesitant to call herself a "curator". For the same reason, Bautista thought it was a term that was easily associated with independent curators who have MFAs and PhDs and museum directors. "However, I feel that with the current changes in the art world in terms of diversity, decolonization of history, challenging the western gaze, etc., the roles and meanings that we attach to titles and claims should also evolve, as with the work."

“If I don’t bill myself as a curator, the public is only open to criticize the artists, the body of works, and space. So, it gives me more comfort that the term is actually more of an accountability than an elitist claim.”

The term curator can be a little polarizing to people who are not too familiar with the job description. There are a lot of people who believe that it's simply about choosing which artwork to place on which part of the four gallery walls, others think they're the untouchables in an exhibition—names without faces, manipulating the exhibition as we see it right before our eyes. This makes the term easy to be thrown around, claimed, and even rejected. How many names have we encountered attached to the curator title? How many of those have actually taken responsibility for their works? It's easy to get away with criticism of an exhibition especially if the curator's name remains on the shadows of the artists they tap to participate in or works they have been tasked to curate. Yet Bautista has pride and holds herself accountable for the exhibitions she curates. "Personally, I do not have a problem with people calling themselves curators. I guess it is the same when people call themselves artists, or poets," Bautista shares. "These titles come with claims that can only be reflected through your work."

"Not all exhibitions start from scratch."

It's always a mystery for people new in the art scene to understand what a curator's task is and where the line is drawn in between tasks of people who organize an exhibition. With Bautista being an independent curator, her tasks vary from exhibition to exhibition. "I don’t really subscribe to rituals and the process can be different because of the requirements of certain exhibitions. Sometimes, you have to work with an existing collection and then assess how you will present it, and in what context, etc." Yet most of the time, it's always about having to manage your time wisely to be able to help produce an exhibition that will have a lasting impact. Having worked as a project manager, Bautista seems to have mastered maximizing time, even when working with friends in those projects. "I respect the time of my colleagues and make sure that when I arrange meetings with them, that something productive will come out of those discussions. But of course, since in the art scene, the professional and personal can become blurry. (laughs) So, I always tell them—and I am very straightforward—“Can we just finish discussing the work first and then let’s talk about the fun parts?” (laughs) But what I find is that the work part is also intertwined with the fun part (almost always)."

"[As a curator,] it is our responsibility to decentralize what little power we may have."

In these days, as progressive as society has become, there will always be questions of how curators remain true to their beliefs. When curating a show, there will be challenges of having to select a diverse set of people, ultimately going beyond the expectations that have been put on the curator. In any curated show today, you'll hear people go for the inclusivity slant. "As a curator, you are in a position of power to choose the artists, the works, etc," she explains. "I try to be as critical and as inclusive as possible. I invite artists based on merits. Maybe because I’m also an artist and an art writer, so these other roles have allowed me to become more aware of the different parts of the art world apart from the exhibition-making." This comes from an experience that is working with artists in the Visayas region. Covering the VIVAEXCON in Capiz as a member of the press, she has realized the lack of platform and support for artists whose practices reside outside of Manila.

“As I always say, time is the only thing I can offer so maybe I should give it generously.”

Since then, Bautista has been going back and forth from Manila to the Visayas to understand and see what she can do to provide help and support to those artists. "I feel that as a curator, we have to invest in understanding these practices. It is our responsibility to decentralize what little power we may have. Sometimes, I see an exhibition and it is usually composed of the same names over and over again. While I understand the convenience of working with people you have known for a long time and I may be guilty of being part of this, so I try to become more conscious about these decisions." These little conscious decisions have then led her to organize The Newsfeed Project alongside close friends who are also in the industry.

"Cian Dayrit, who is a good friend invited me to co-organize the show with him and our other friend Renz Baluyot," she shares. "We invited around eighty artists to present works that reflect the current times, as a physical composite of our social media feed." Much as our social media feed varies due to the way algorithms work, The Newsfeed Project reflects a real-world representation of it. The exhibition did not have any influencer on a beach getaway vacation or images of food served in pretty plates, filtered to make it look more alive. This real-life social media feed projects what is real and what is now in diverse media and selection of artists. The roster of artists is not only from Manila but from different parts of the country such as Bacolod, Bohol, Cebu, the Cordilleras, Davao, Dumaguete, Iloilo, and more. The media of the artists are just as varied allowing for Bautista and other artists to learn more about different approaches and techniques in image-making.

"Well, I’d say my practice is still young and I look forward to learning more from experienced senior curators."

On a humble note, Bautista shares that there's still so much to learn for her when it comes to curatorial works. As much as she's been one of the familiar names in the industry, she still aims for a greater understanding of a curator's job. "I guess the most important part that you have to reconcile first is to understand what you came here for. Why do you want to become a curator? It’s so easy to get lost when people start inviting you to nice dinners and parties, getting yourself hyped by the media (laughs) but at the end of the day, when you come home, when you no one is watching you, take a deep breath and just remember what you really came here for."

What helped Bautista go beyond the years of having to dismiss herself with the curator title is an open mind to learn and to grow. She's joined programs like The ESKWELA program of Bellas Artes Projects and curatorial workshops organized by the Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation. And even when rage calls for it, Bautista refuses to succumb to anger in times of miscommunication and misunderstanding. "There are ways to communicate properly and get everything done without fighting, yelling, or calling people out on social media. Be more forgiving but also stern."

Today, Gwen Bautista remains to be an independent curator while still pursuing being an artist and a writer. She continues to help provide avenues for artists to grow and flourish, especially those with little to no platforms to help them. She's also recently become a part of the Mono8 Gallery team and has been planning a lot with the director, Carlo Reyes. "My goal is to have exhibitions that feature practices instead of objects and to have more public programs, especially that we are located at the heart of the historic Ermita district. We also started opening artist residency programs and I am currently working with our Director, Carlo Reyes, to develop and implement the programming." Aligned with her vision, Bautista is also working with an artist-run contemporary art space in Iloilo, Mamusa Art Gallery. "The owners are artists themselves and are committed to engaging the local art scene to support contemporary artists in Iloilo. We’ll be working with different sets of programs and events to ensure we activate the space and find more audiences within the thriving Iloilo art scene."

To Bautista, the little things she does for the art scene is a great help for an artist or enthusiast out there. Curating is not a two-dimensional job and it's done a great deal for her to help other artists like herself, one way or another.