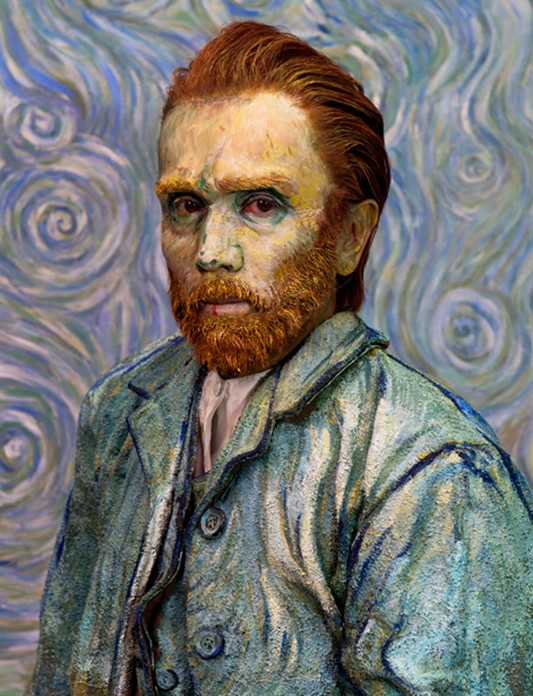

He has been Vincent Van Gogh in a self-portrait after he severed his ear, Marilyn Monroe in the Playboy Magazine centerfold, Leonardo da Vinci, and Frida Kahlo on various occasions. All these people and more including other places in art history are where we'll find Japanese appropriation artist Yasumasa Morimura.

In 1988, Yasumasa Morimura photographed himself as the subject of Édouard Manet's Olympia, the realist painting of a naked lady (who is "Olympia") served with flowers by her servant. He called it Futago (meaning Portrait) This very description of the original painting was what Morimura was challenging. Throughout his works, the artist underlines the meaning of "the self" and alters our perspective of cultural and art history. Suddenly, what we see on the 1988 work by Morimura is not defined by race, gender, sexuality, and identity but how the artist has put himself in the work and embedded the work onto himself.

30 years after Futago was rendered, Morimura recreates the scene with the original background and set he made himself then. A few things have changed though. The 2018 work is now called Une moderne Olympia and the artist is older and wiser 30 years later. "The entire journey of my thoughts and changes in that 30-year timespan is embedded into the "reborn" one," Morimura explains. These peculiarities are what sets Morimura's works apart from the many appropriations in the arts.

These works—both Futago and Une moderne Olympia—were at the center of his New York exhibit, Ego Obscura. The show highlighted much of art history and where he finds himself in each situation. With Van Gogh as his first-ever art- historical self-portrait subject, Morimura found himself empathic towards the art history icon. This was in 1985 when the artist was in his mid-thirties, in the middle of a crisis of knowing what to do for the rest of his life. "I was at a standstill," he tells. "My suffering at the moment was overlapped with Gogh’s anguish, and that’s why I chose Gogh’s most tragic expression, cutting his ear.”

Photo courtesy of Yasumasa Morimura

at Minneapolis Institute of Art

The pattern to which he creates his self-portraits in the shoes of these art history and pop culture icons is seeing himself as them as if looking at his reflection as in a mirror. To him, this is what makes the experience of the process of creating such self-portraits strange to him. One of the many self-portraits he made was an appropriation of Albrecht Dürer's self-portrait. "This might sound strange, but if the frame contained a mirror, instead of [Dürer's] self-portrait, then I would be seeing myself in the mirror. And if the painting is a mirror and also showing Dürer, that means I myself am Dürer. Also, if I am myself, the image shown on the painting-mirror is me. To put it simply, I feel Dürer in myself and myself in Dürer; this relationship is constructed within me by looking at his self-portrait.”

"This is not a painted self-portrait, but a photographed self-portrait," Morimura explains. "This distinction is very important to me." These works are a reflection of Western influences on post-war Japan. Born after the Second World War, Morimura was one of the many Japanese who were molded by Western influences and that includes art history. Through the process of creating self-portraits, he finds himself inevitable a representation of Japanese traditions buried at the light of peace as they were considered "a trigger of war."

Yasumasa Morimura's medium is indescribable by paint, paper, print, or photographic technique. His true medium lies within the self. What lies beyond the surface of his works is a hypercritical means of finding a place in momentous occasions or in the shoes of icons. These paintings portray how time ages oneself even when it's latent in portraits seemingly timeless as narrated in history.