When I visited Mark Justiniani’s latest exhibition, The Philippine Wine Dance, at The Drawing Room in February, I was struck by how seamlessly the artist continues to expand his distinctive visual language. This new body of work—11 tricycle-inspired pieces and a monumental spherical infinity mirror installation—reflects Justiniani’s evolving mastery. He melds painting, installation, philosophy, and visual storytelling into a cohesive and compelling vocabulary. Even before reading the wall text, it was clear this exhibition marked a full-circle moment: echoes of his earlier Jeepney

and the Infinity series reverberated throughout the space.

Justiniani’s enduring fascination with palindromes, physics, and Philippine art history comes into sharper focus in each of the works featured in the exhibition The Philippine Wine Dance. He draws on familiar cultural elements—like the tricycle—and reimagines them alongside an immense infinity mirror piece that evokes the sensation of cosmic drift, offering the viewer a portal to the infinite—no spacecraft required.

This article is based on a recent interview I conducted with the artist, where Justiniani unpacked the layers of meaning embedded in his new works. At first glance, the works unfold like a journey through Philippine art history and contemporary practice. In our conversation, he illuminated the internal dialogue embedded in the series, particularly the imagined mental battle between Victorio Edades and Guillermo Tolentino. At its core was a pivotal debate over classical ideals of beauty and order—a conflict fought not through images but through rhetoric, where the power of persuasion determined the victor. In one work, he revisits Fernando Amorsolo, whose idyllic portrayals of Filipino life were challenged by the rise of modernism, igniting a broader discourse within Philippine art.

In others, he engages with broader philosophical, aesthetic, and cultural movements—from classical drama and modernism to contemporary conceptualism. They offer a layered critique of the very idea of the “masterpiece” and pose questions about who and what defines an artist, all while grappling with politics, religion, and society. Justiniani’s deliberate fragmentation invites viewers to reconsider canonical narratives, using precise language and stark juxtapositions to explore the friction between tradition and transformation. His enduring wit and intricate wordplay unfold across mirrored surfaces, where infinity becomes both a visual device and a conceptual strategy. It makes me wonder where the real trick lies: in the illusion of Justiniani’s infinity works, the flipped text, or the imagery and history from which they were shaped?

Whether consciously or not, Justiniani invites us to board a distinctly Filipino vehicle—be it the humble tricycle or a metaphysical spacecraft—and traverse the terrains of history, perception, and possibility. Through this playful, complex, and luminous lens, his art continues to challenge and enchant.

The first question that came to my mind was: Why call it The Philippine Wine Dance? With this title, I began reading each piece, trying to align the choreography of The Philippine Wine Dance with my limited knowledge of physics. Not to mention the complex thinking and embodied imagination across a wide array of topics that the artist wishes to articulate. The delicate balancing act of the Philippine Wine Dance—gracefully carrying wine glasses on the head and hands—echoes how words and imagery are positioned within Justiniani’s compositions. Central elements are arranged to create an illusion of depth, offering multiple interpretations. I imagined the dancer balancing the glasses as the artist balances his elements—words positioned on all sides, with the core imagery at the centre, capturing both stillness and movement.

Instead of addressing my inquiry directly about the title, Justiniani retorted with the key conceptual thread that begins with the question: When was light born? Here I was, circling and moving my body to understand the thinking behind both the exhibition title and the work's composition. Justiniani explains that people’s instinctive response usually references the Biblical creation story—Let there be light. However, he invites deeper reflection: Is there light without a perceiver? While organisms react to light, he argues that brightness—a sensory experience—is dependent on perception. Light, as an energy wave, exists independently, but brightness needs eyes and contrast to be realised.

Building on this idea, Justiniani discusses the concept of ‘kislap’ (Tagalog for ‘spark’ or ‘flash’) as a poetic metaphor for the genesis of perception and division. Drawing from his readings on the Big Bang theory, the artist notes that the universe remained opaque for approximately 380,000 years because particles were too dense and charged to form light. He continues by explaining that only after cooling did electrons and protons combine to create the first photons, making the universe transparent and allowing light to travel—what we now detect as the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB).

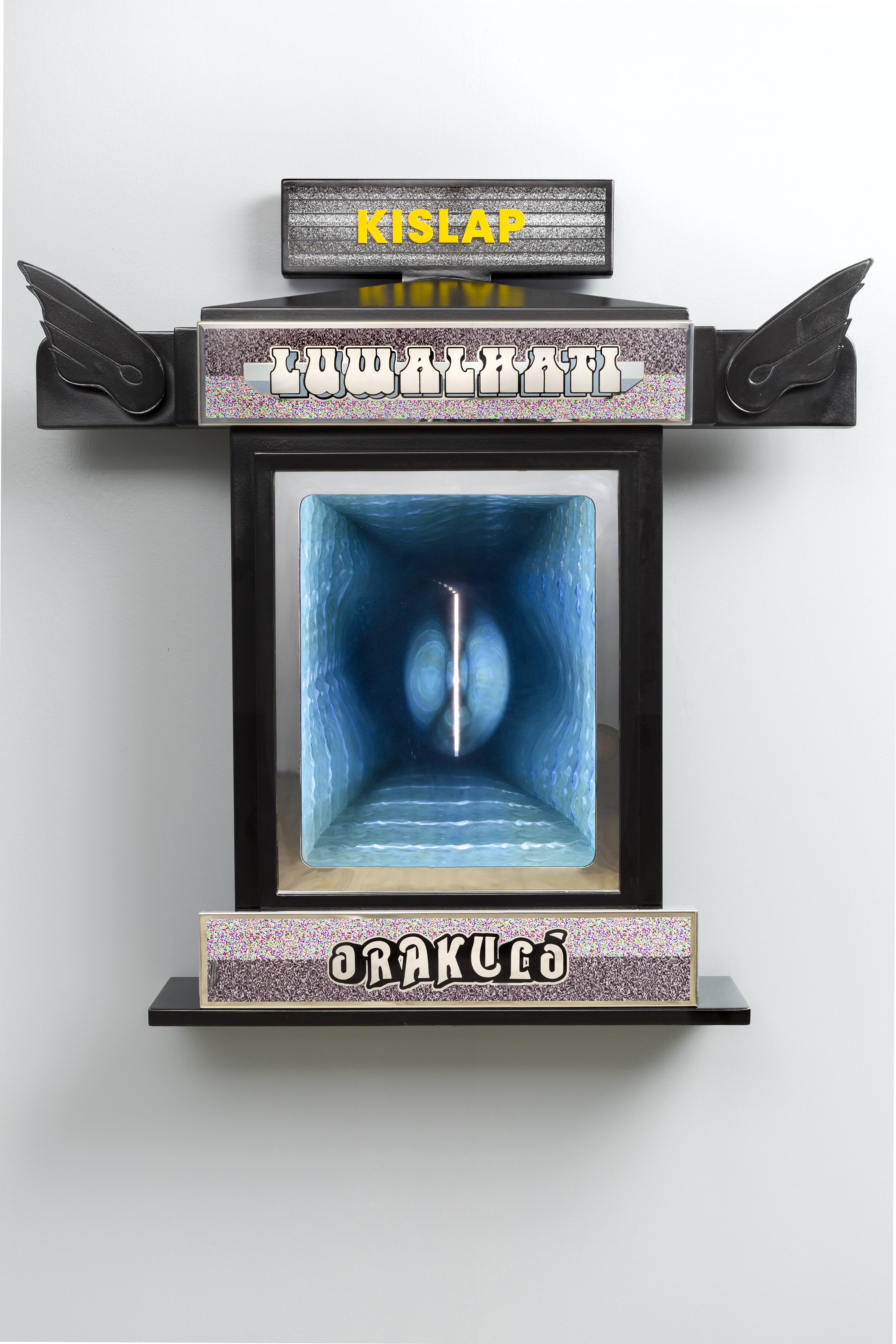

Justiniani cleverly weaves this scientific history to his installation. In the work titled “Luwalhati” (loosely translated to ’glory’ or ’splendour’), ‘kislap’ is given a visual form that mimics television static, like the primordial flash that marks the start of perception. This motif, referencing remnant radiation from the early universe, becomes a metaphorical echo of the first light. Behind the word kislap in the work, the static-like imagery serves as both a literal and conceptual backdrop, linking cosmological history with perceptual awakening in a gesture that fuses science, language, and aesthetic experience. The static, then, is not merely a reference to outdated media but a metaphor for the unresolved frequencies of the cosmos—an echo of light in search of meaning.

Justiniani delves into the etymology of ‘luwalhati.’ In Filipino, ‘luwal’ implies ‘to bring forth’ or ‘to give birth,’ and ‘hati’ means ‘division.’ Thus, ‘luwalhati’ can be interpreted as ‘to give birth to division,’ a surprising yet profound rethinking of the term often associated with transcendence or glory. In this context, creation is seen as an act of division—an emergence from unity into multiplicity, echoing scientific and metaphysical ideas of the universe's birth.

The visual representation in his piece shows this division through a ‘warp’ or ‘tear’ that seems to fold space, with a scab-like structure symbolising healing and boundary. Waves sculpted in transparent resin converge in a central warped space, suggesting a cosmic split. Depending on where the viewer stands, the forms on the right or left may appear enclosed, reinforcing the notion of division and polarity inherent in the act of creation.

Additionally, Justiniani incorporates an ‘oracle’ at the base of the work—a medium that bubbles and churns with time, emphasizing transformation, prophecy, and the unseen forces guiding existence.

The interview also reveals the organic way in which Justiniani’s ideas evolved during the creation of the exhibition. His process wasn't linear; questions such as the origin of light, the nature of perception, and the role of division emerged and matured as he built the show. Physical elements like tricycles and jeepneys—ubiquitous Filipino modes of transport—also became significant metaphors. The tricycle’s window represents the viewer's journey, suggesting that the audience is not a passive observer but an active traveller being taken somewhere conceptually.

Justiniani details how everyday parts of these vehicles—the crown (visor), bumper, and side flaps—became structural components in the works. The crown bears the word ‘kislap,’ the bumper references the cosmic journey, and the side flaps hint at both protection and openness. Through this familiar yet deeply symbolic imagery, he grounds cosmic questions in tangible, relatable experiences for Filipino audiences.

One can also analyze the components and connect them to the longstanding influence of Catholicism in his works. As a reader or viewer, one can contemplate the sign of the cross and examine the parts of each work separately—as if reciting: “In the name of the Father (crown/forehead), the Son (heart), the Holy (left shoulder) Ghost (right shoulder), Amen (navel).”

In response to a question about the piece “Kislap,” where the term ‘aninag’ (shadow or faint light) appears, Justiniani explains that it symbolizes the subtle gradients of light preceding full illumination, highlighting the gradual nature of perception and understanding, as opposed to instantaneous insight.

With a long list of works in the exhibition, Justiniani meticulously explains and dissects each piece, generously sharing his process and thoughts behind them. At its core, his work reflects the intricate interplay between science, philosophy, and local cultural motifs. He offers layered experiences that invite viewers to contemplate vast, abstract ideas—such as the birth of light, the nature of perception, and the inherent divisions of existence—through the lens of Filipino language, imagery, and everyday life.

In doing so, Justiniani’s work transcends visual spectacle, becoming an incantation—much like Con Cabrera's fragmentary exhibition text for the show—that suggests each piece is a distinct entity inhabiting a shared and interconnected space. It invites reflection on our place in the cosmos, the invisible threads connecting the micro (individual lives) to the macro (the universe), and the ongoing process of creation and division that shapes existence.

Over the past eight years, I have had the privilege of working closely with Mark Justiniani. Our collaboration has extended beyond exhibitions into deep, sustained conversations about light, time, and perception, profoundly shaping my thinking as a curator and viewer. Engaging with his Infinity works and witnessing the evolution of his cosmological explorations have taught me to read his art as formal installations and conceptual portals. They offer pathways into scientific inquiry and the cultural psyche of the Filipino experience. In tracing the luminous threads of his practice, I continue to see how Justiniani’s art challenges and expands the ways we perceive space, memory, and meaning.

Vanini Belarmino is working at the intersection of contemporary art and performance, focusing on interdisciplinary collaborations and site-responsive interventions. Founder of Belarmino & Partners (Berlin, 2008; Singapore, 2011), she has led projects across Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. Her landmark project, In Situ, Performance as Exhibition (2024), activated landscapes and urban sites in Singapore and the Philippines. As Assistant Director (Programmes) at National Gallery Singapore, she commissioned over 60 site-specific, participatory, and immersive works and curated three editions of the Gallery Children’s Biennale (2017, 2019, 2021). She co-curated Afterlude-Prelude, Responses to Nam June Paik (2021) with SFMoMA. A fellow of the Asian Cultural Council (2009, 2014) and International Society for Performing Arts (2009, 2011), her essays have been published by Routledge, Roulette Russe, and Independent Curators International (ICI).