On January 7, 2023 the exhibition You Betrayed the Party Just When You Should Have Helped It was to open at the UP Vargas Museum, but only at the end of the day. In the morning were events that preceded it: a roundtable discussion with academics from the University of the Philippines Diliman campus in conversation with the exhibition’s leading artist Andreja Kulunčić, and a clay modeling workshop with Kulunčić in the afternoon. I eventually learned that two days before the exhibition’s opening, a translation session with select scholars was held as well. As a cultural worker with an inclination for arts education, I was definitely curious as to why for this show, the pedagogic aspect took place before the exhibition’s opening. I attended the second activity, the clay modeling workshop.

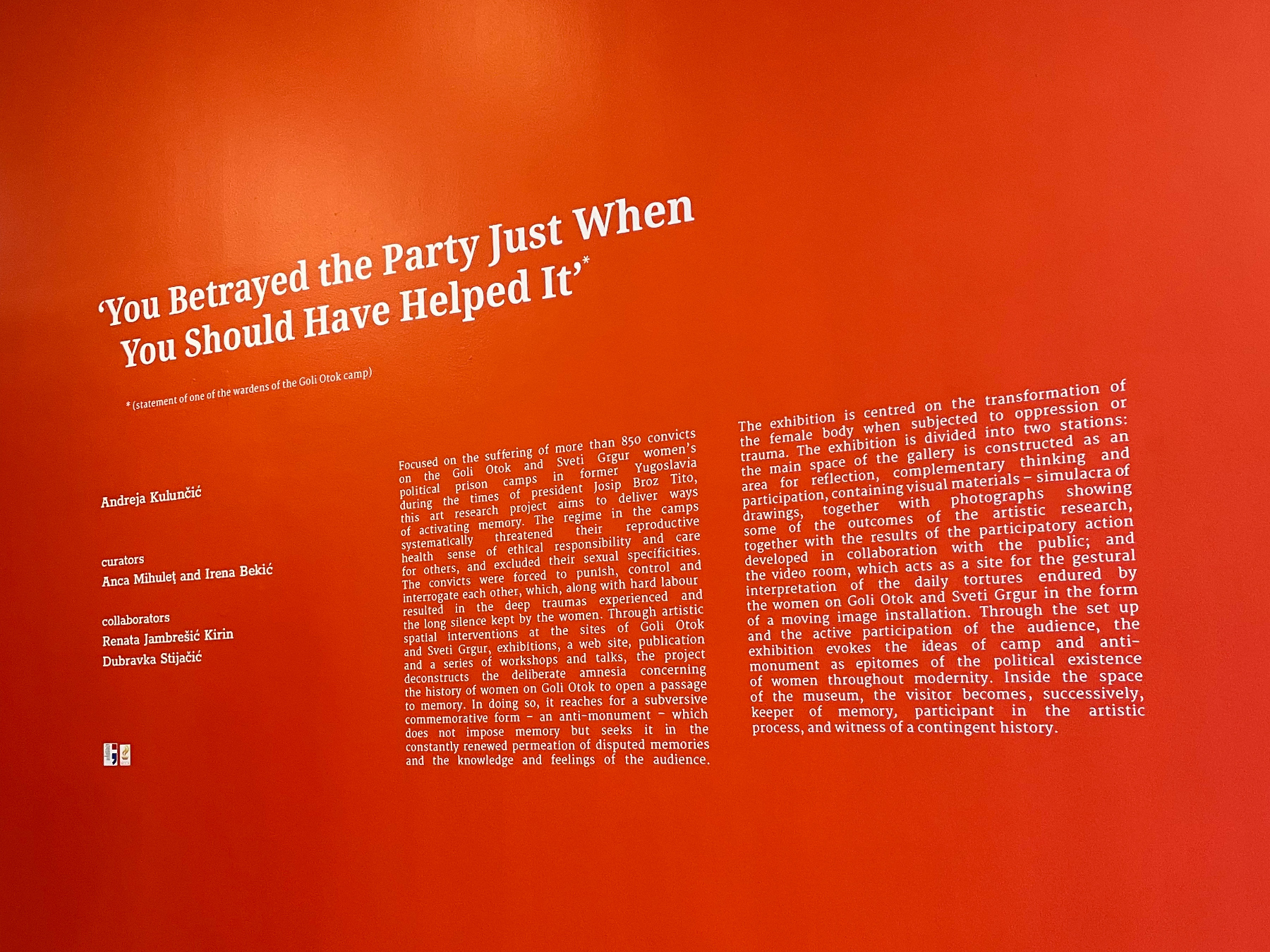

Bright red. Very bright. That was the color that welcomed us at the Vargas Museum. It is this color that was used to paint the wall which carries the exhibition’s title and wall text. Because of the saturation I had initially mistaken the shade of the walls to be a brilliant/vivid orange, only to be corrected later on, that it was in fact“communist red”. It is this specific shade of red that set the stage for the stories that the artist Kulunčić and her collaborators anthropologist Renata Jambrešić and psychotherapist Dubravka Stijačić, together with curators Irena Bekić and Anca Verona Mihulet will be telling during this first iteration of the exhibition in the Philippines.

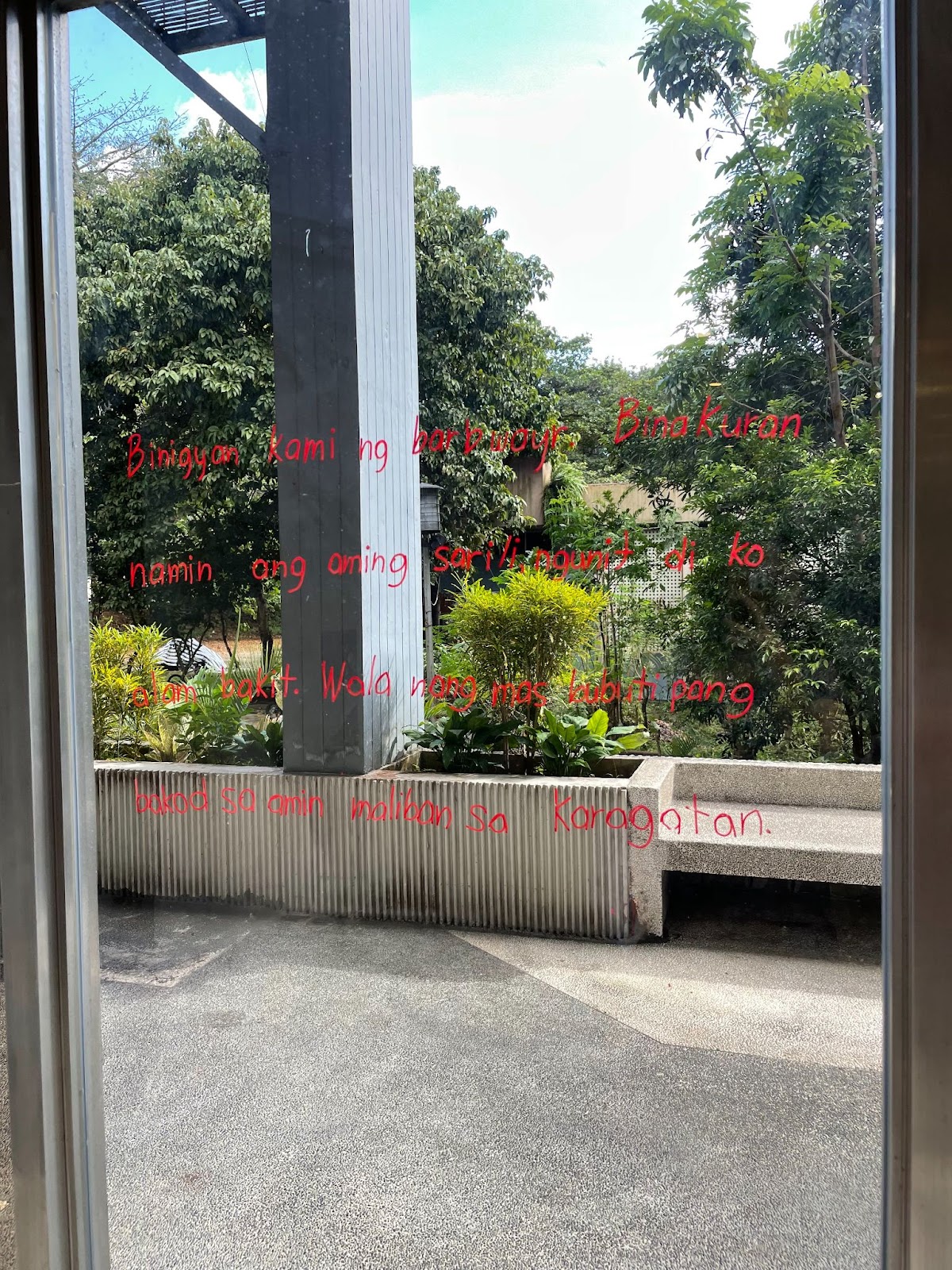

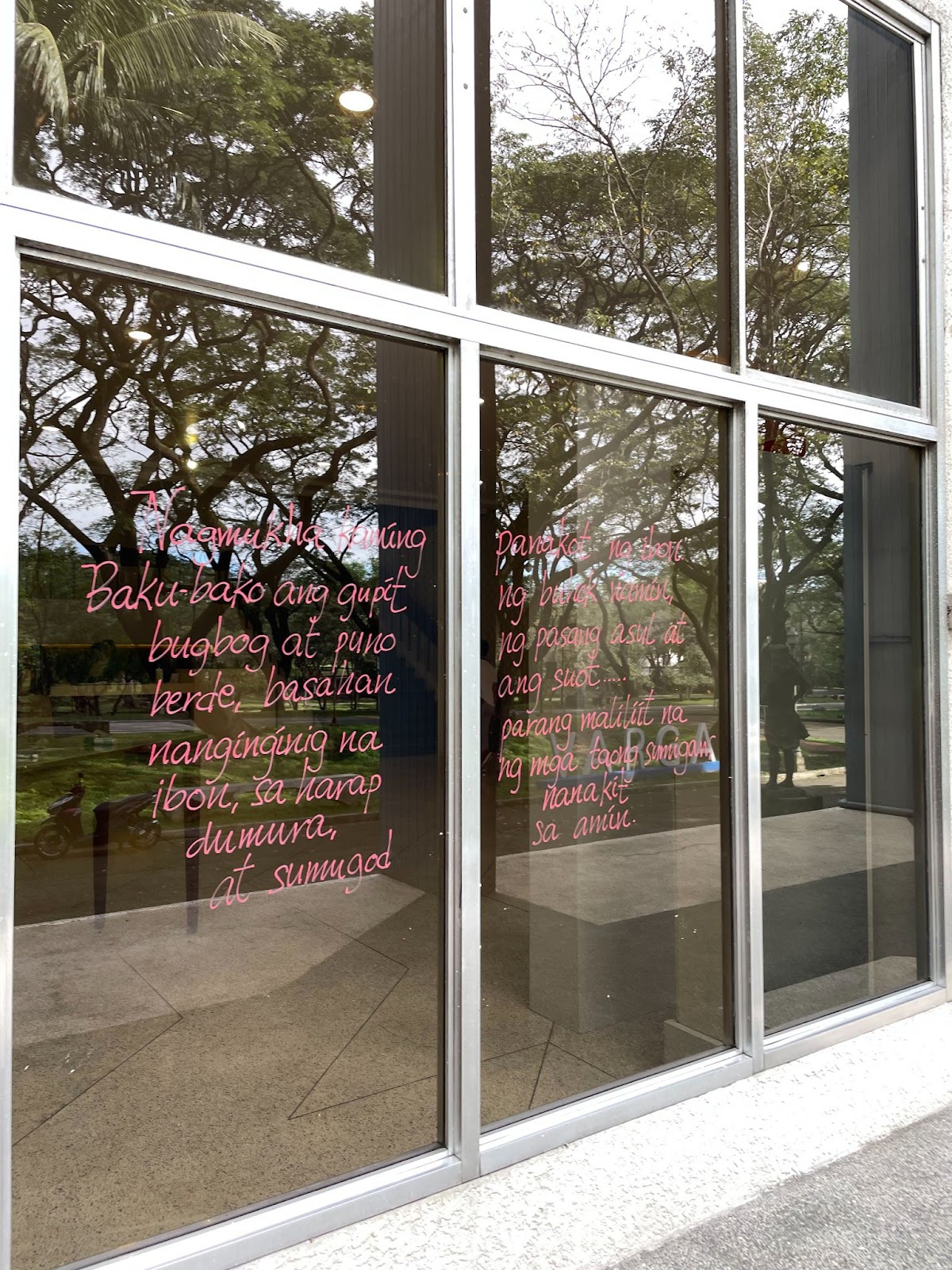

And what was there to see? Surprisingly, not artworks at first, or not yet. At the museum lobby could be found two blank floating panels, two long plain wooden tables flanked by wooden chairs, two large empty hardwood glass cabinets, a white console table with stacks of blank post-it notes, markers, and bulletin board pins. The artworks were to be found in a separate gallery swallowed in more of that red. On the walls of the museum anecdotes written in Tagalog spoke of harrowing experiences of alienation and oppression, and were of course inscribed in red ink as well. I learned later on that these writings were the fruits of the translation session held on January 5.

When it was time for the clay workshop to begin, Kulunčić first asked: have any of you seen the artworks yet? Most of the participants for the clay modelling workshop had not. Before we could touch any kind of clay, she hoped to help us understand where the exhibition is coming from. Gathered around the long wooden tables, Kulunčić began to speak of a piece of Croatian history that I had not known of at the time, but which frightened and haunted my gendered body: the story of the Goli Otok women’s political prison. She spoke of the traumas endured by the camp’s detainees from 1950 to 1956, operated under the rule of Josip Broz Tito and the Yugoslav Communist Party, warning us well of the path of the metanarrative that conveniently brushes aside the camp’s existence—along with it the experiences of the women held captive there. In a world where women are rewarded for their silence and submission until their death, You Betrayed the Party Just When You Should Have Helped It treads the more difficult route of kicking and screaming to keep the stories of the women alive.

After our history lesson, Kulunčić brought us into the art exhibition space. The artworks were humble in terms of medium, but they hummed with an enigmatic power upon the first encounter. And how could they not, with the weight of the history that belied their creation? The first work brought to our attention was a photograph of a steel plate, captioned Photograph of the information board on Goli Otok. The photograph’s caption card explains:

“In September 2020, 64 years after the female political prisoners’ camps on Goli Otok and Sveti Grgur were dissolved, for the first time in the history of the islands, Andreja Kulunčić installed an inscription as part of the project, representing a trace of the organization and history of the camps. The steel plate was placed on one of the outer walls of a building belonging to the women’s prison on Goli Otok, and it signifies a gesture of the responsibility assumed by the artist that makes up for the lack of interest on the part of the authorities.”

It was the perfect work to introduce any museum visitor to the exhibition’s project, as the steel plate copied the language of authority used by most governments when it comes to the surveying of land: the language of monumentation. The photograph gained more significance when Kulunčić informed us that authorities had taken down her steel plaque in a quiet but violent act of historical erasure.

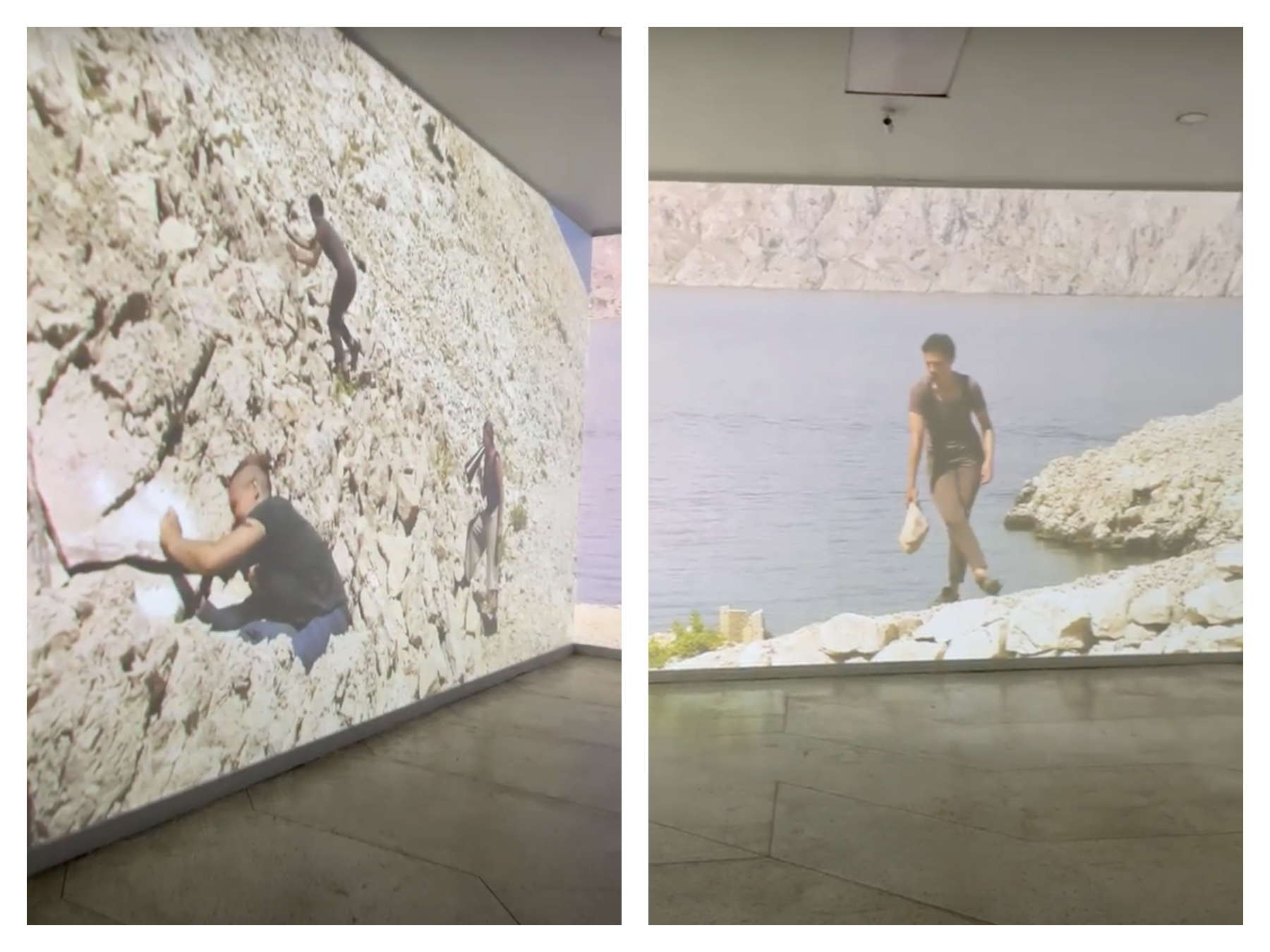

More photographs were spread across the landscape of the gallery: photographs of the artist’s drawings depicting female bodies screaming, hunched over, carrying rocks, and laboring; some bodies were cut out and transposed to other sheets of paper in a never-ending act of permeation. There were photographs of what appeared to be the land at Goli Otok. But beneath these photographs was an LCD monitor that showed the hands of Andreja Kulunčić pinching, pressing, and molding wet clay onto the Goli Otok terrain where the female prisoners would labor, where they had picked at and carried blocks of stone. I immediately understood the gesture but sought confirmation from Kulunčić: “That gesture of spreading your clay into the gaps of stone evokes a feeling of nurture, almost like you are placing a salve onto the land.” She nodded profusely: “Yes, exactly. It is very much like a salve.”

To heal the trauma inflicted by the ways of the world onto the female body seems like a monumental task, but in the words of one of my mentors from a feminist workshop “If the problems of the world are big, why can’t we dream bigger?” And it is this idea that powers the exhibition, as it forges a path to healing through the language of materiality, memory, and community. The exhibition presents this ongoing project as the ‘anti-monument’, which curators Bekić and Mihulet describe as “a subversive commemorative form […] which does not impose memory but seeks it in the constantly renewed permeation of disputed memories and the knowledge and feelings of the audience. The anti-monument thus opens the process of decentralizing collective memory and acts as the filter of acceptance of the past. In this sense, it actively encourages discussions about how we remember, what we remember, and the role of the past in the future.” To flesh the idea further: the ‘anti-monument’ is very much unlike an individual statue placed by people and systems of power at the center of a public space, declaring a specific area of land to be of undisputed historical value. The anti-monument is understated. It listens to the land and it listens to the people, creating space for long-marginalized histories and alterities to exhale. It is an enduring project of collective empathy and collaboration.

The first example: the video installation at the end of the museum’s 1/F gallery, which shares the title of the exhibition. This combination of performance and new media art was done in collaboration with vocalist Annette Giesriegl, instrumentalist Jasna Jovićević, and dancer Zrinka Užbinec. The artists filmed themselves on the sites of Goli Otok and Sveti Grgur recreating the actions, the sounds, and the sensations that the female political prisoners at the camp may have done in repetition during their six years of encampment. Under the bright and harsh heat of the sun, Užbinec carries a huge chunk of rock around her body over and over again, never once losing contact with the stone. Giesriegl howls repeatedly into the horizon of a vast, blue, and empty sea. Jovićević scratches, picks, and knocks at the rocks on the ground. Collectively, they summon the ghost of the land’s past into the present and remind us that a sound is still a sound around no one.

The second instance: the translation workshop. The texts written in red all over the windows of the museum’s first floor were documented testimonies of former detainees translated from their original language into Filipino. This participatory act of discussion and eventual translation ensures another pathway for connection to the exhibition’s first Philippine audience.

The third instance is what became the crux of the exhibition—the very reason why the show could not open until the pedagogical activities had taken place: the clay modeling workshop. More malleable than metal or stone and soothing to the touch, coupled with Kulunčić’s background as a sculptor, it was only natural for her to look to the medium of clay as the primary language for the anti-monument. But the act of sculpting with her own two hands was not enough for the artist and as such she conceived of a participatory experience using the medium. At this point, this very participation-driven clay modeling workshop by Kulunčić had been done all over the world, in countries that have also been under dictatorships.

After the artist’s walkthrough, we were once again sat around those long wooden tables, this time with a big block of clay before us that hummed with potential. The artist asked us to think of specific histories that have witnessed the realities of female trauma, which are often histories that have been marginalized by the ebb and flow of history’s often patriarchal metanarrative. Everything that we had just witnessed was our prompt for creation. Other participants sculpted figures of women based on what they had just seen: hunched over or toiling, much like the women on Goli Otok. Others drew from local histories, like my partner who sculpted an empty box. A box with no top, resembling a coffin with no body. When Kulunčić saw what he had sculpted she asked him “Is it conceptual?” He tells her that it sort of is and explained that he tried to make a crib: a dedication to the widely covered story of baby River, the late infant of detained Filipina activist Reina Mae Nasino. Baby River, needing the nurture of her mother’s breast milk to stand a chance against disease, passed away at two-months old after being separated from her mother by authorities. Kulunčić shares a solemn nod, thanks my partner for sharing Baby River’s story, and asks him to do the following: to place his sculpture on one of the shelves within the hardwood cabinets, then to take a post-it note, write down the intentions of his work, and stick it onto one of the blank floating panels.

As I continued to sculpt my own contribution to the exhibition, I watched the shelves on the cabinets become populated with all kinds of clay bodies. I watched my fellow participants scribbling down on post-it notes and tacking it onto the once white walls, covering them in tiles of color and sentiment. It was the spirit of the exhibition showing through, the very thing it needed before its opening night. An act of communion. Placing my finished sculpture amongst the others, I witnessed the anti-monument in action: a conscious and collective remembering made real.

You Betrayed the Party Just When You Should Have Helped It is on view at the 1/F Galleries of the Vargas Museum until March 16, 2023.

Corinne Fernandez Garcia is a feminist visual artist, writer, designer, & cultural worker from the Philippines. She graduated from Ateneo de Manila University with a BFA in Information Design and a Minor in Philosophy in 2018. Her works often articulate her observations on the intersections of memories, places, bodies, and patterns, and their relation to time. As an artist, her works were recently exhibited at Imahica Art Gallery, 98B Collaboratory, and the Ateneo Art Gallery through the Marciano Galang Acquisition Prize, of which she was a recipient in 2020. She has had her visual and written works published in HEIGHTS Ateneo & The Brown Orient Journal. She is currently the Education and Public Programs Assistant at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila.